Gilbert Murray - Hellenism And the Modern World

Here you can read online Gilbert Murray - Hellenism And the Modern World full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1954, publisher: The Beacon Press, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Hellenism And the Modern World

- Author:

- Publisher:The Beacon Press

- Genre:

- Year:1954

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Hellenism And the Modern World: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Hellenism And the Modern World" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Hellenism And the Modern World — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Hellenism And the Modern World" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

BY GILBERT MURRAY

THE BEACON PRESS BOSTON

-3-

Copyright, 1954, by The Beacon Press

Printed in U.S.A.

-4-

T HESE TALKS were given first on the Radio-diffusion Franaise in 1952 and repeated, with some revision, on the BBC Home Service in April-May 1953. In the meantime, however, I had listened to those fascinating Reith Lectures on "The World and the West" with which Arnold Toynbee shook us all from our dogmatic slumbers. I thought at first that I should have to make some changes, or at least some withdrawals of rash statements, in my script. But it was not necessary. Even in that small part of his vast canvas where we were dealing with the same subject our focus of interest was different. I was trying to trace the special development of that 'Christian' or 'Hellenic' civilization to which we peoples of Europe and the English-speaking world historically belong, and to consider how, amid multifarious 'barbarian' influences it may still preserve or even raise its traditional standards, and continue to set to the whole world an example of what is meant by civilization. Mr. Toynbee carefully abstained from any such self-admiring prejudice, observing that naturally every nation thought its own ways the best, and merely noting objectively the 'aggressions' and 'reactions' between them. One lesson at least which

-5-

we of the West may learn from Mr. Toynbee's book will be to take great care, when we are bringing help to some 'barbarian' or 'less advanced' nation in need, that what we think of as generous help may not seem to the recipient more like contemptuous almsgiving or even arrogant interference.

I hope I am not blind to the defects of our western civilization or oblivious of the terrible wrongs done throughout history by the dominant races of mankind to those who stood in their way. Yet I feel strongly that the Western Community, with all its faults and vulgarities, and with all that it still has to learn from certain Eastern nations, is nevertheless, in virtue of its Hellenic and Christian heritage, called upon to lead the world. "The present is hard and the future veiled"; and we have a very great civilization to lose or save. It is not an effete or corrupt generation that responded with such instant enthusiasm to the vow of dedication and service undertaken by our young queen; not a cynical world which, after the disastrous failure of its hopes in the League of Nations, has so almost unanimously pledged itself again to follow the same practical ideal; not a hardened or unrepentant community which is pouring out such a vast flood of charity and remedial measures from every possible source, personal, social, religious and governmental, in its longing to redeem the wrongs

-6-

of the Second World War. The silent undercurrents of human feeling are, I believe, far nobler and in the long run more important than the much publicized conflicts of national or sectional ambition. Of course all is in danger. But I see no reason to doubt that our Christian or Hellenic civilization is on the right road; certainly no reason to lower our traditional standards or abate our old courage.

G. M.

-7-

|

|

|

THE CHRISTIAN TRADITION: ROME, JERUSALEM, ATHENS

E VERY CIVILIZATION has its roots in the past, and Europe has a great civilization of which we Europeans are all extremely conscious, though we hardly know what name to give it. We sometimes say 'Christian', sometimes 'Hellenic'. Of course, historically, we all have millions of ancestors: Europe is the product of multitudes of different nations and histories; yet it is surprising how little permanent effect most of them have had. Allowing for a vigorous influence from the North and a little, mostly unconscious, from the East, our vital inheritance seems really to come from three particular cities: Athens, Jerusalem and Rome.

The Roman influence is everywhere. It is by far the most visible and striking; but in almost every case, when we look beneath the surface, the real moving power is Greek. Our Latin alphabet is really Greek, our Roman Law Greek in origin, our political ideas almost entirely Greek. We even describe the tradition

-11-

as 'Hellenic' because, as the Roman poet says, "Graecia capta ferum victorem cepit": "captured Greece made her rude conqueror captive". Greek culture was moving on much the same lines as Rome, but happened to be more advanced; also, Greece had from the most primitive times an extraordinary command of language: at a stage when other peoples could scarcely mumble, the Greeks were clearly articulate. They could think clearly; they could explain and teach.

In the ordinary regions of scientific knowledge Rome had simply to follow the lead of Greece. She had to learn from Greece her architecture, her field measurements, her seamanship and navigation, her medicine, her geography, geometry, astronomy and mathematics in general. We do not notice our dependence on Greece and Rome in such things, because discoveries in science, however glorious to the discoverer and important to society, are quickly surpassed by further discoveries and made obsolete. But in the region of things that are not ever surpassed, the regions of imagination and aspiration, Greece had the same unquestioned lead. A Roman with a love of poetry in the first or second century B.C. found abundance of magnificent Greek poetry to read, and very little in his own language or elsewhere. When Virgil's genius sought expression,

-12-

it found it in the sort of pastorals that Theocritus wrote, in the poems about fields and crops and bees that Hesiod and Artus wrote, or in some part of the great heroic or romantic tradition expressed by so many Greek poets from Homer to Apollonius. Horace, a great original poet himself, can give no more emphatic advice to a young poet than to turn over his Greek models night and day. When Lucretius wanted to find the true secret of the universe, he could only go to a Greek philosopher for it; when he wanted the proper technique for expressing it in such a way as to move mankind, he went to Greek poets. The philosophy which moved the Romans most was, characteristically, that which was concerned with practice and told men and statesmen what to do. It was ethics, politics and, to some extent, religion. That sort of thing was only to be found in Greek writers. The Latin language had not even the necessary vocabulary, until great masters of language like Cicero invented the suitable words and could proceed to translate and explain. It is interesting to notice that Cicero, the first Roman philosopher, translates from the Greek, but in less than two centuries later the chief Roman philosopher of that time, Marcus Aurelius, actually writes in Greek. Roman civilization, as it became more perfect, became more Hellenic,

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

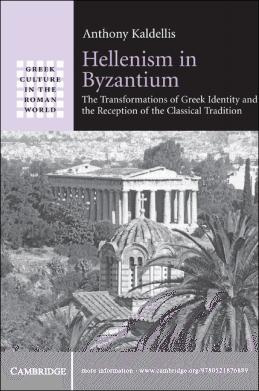

Similar books «Hellenism And the Modern World»

Look at similar books to Hellenism And the Modern World. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Hellenism And the Modern World and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.