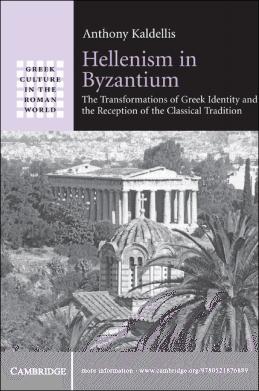

Hellenism in Byzantium

This is the first systematic study of what it meant to be Greek in late antiquity and Byzantium, an identity that could alternately become national, religious, philosophical, or cultural. Through close readings of the sources including figures such as Julian, Psellos, and the Komnenian scholars Professor Kaldellis surveys the space that Hellenism occupied in each period; the broader debates in which it was caught up; and the historical causes of its successive transformations. The first part (100400) shows how Romanization and Christianization led to the abandonment of Hellenism as a national label and its restriction to a negative religious sense and a positive, albeit rarefied, cultural one. The second (10001300) shows how Hellenism was revived in Byzantium and contributed to the evolution of its culture. The discussion looks closely at the reception of the classical tradition, which was the reason why Hellenism was always desirable and dangerous in Christian society, and presents a new model for understanding Byzantine civilization.

ANTHONY KALDELLIS is Professor of Greek and Latin at The Ohio State University. He has published many articles and monographs on late antiquity and Byzantium, and is currently completing a related book on the subject of the Christian Parthenon. His most recent titles are Mothers and Sons, Fathers and Daughters: The Byzantine Family of Michael Psellos (2006) and Procopius of Caesarea: Tyranny, History and Philosophy at the End of Antiquity (2004).

Greek Culture in the Roman World

Editors

Susan E. Alcock,

University of Michigan

Ja Elsner,

Corpus Christi College, Oxford

Simon Goldhill,

University of Cambridge

The Greek culture of the Roman Empire offers a rich field of study. Extraordinary insights can be gained into processes of multicultural contact and exchange, political and ideological conflict, and the creativity of a changing, polyglot empire. During this period, many fundamental elements of Western society were being set in place: from the rise of Christianity, to an influential system of education, to long-lived artistic canons. This series is the first to focus on the response of Greek culture to its Roman imperial setting as a significant phenomenon in its own right. To this end, it will publish original and innovative research in the art, archaeology, epigraphy, history, philosophy, religion, and literature of the empire, with an emphasis on Greek material.

Titles in series:

Athletics and Literature in the Roman Empire Jason Knig

Describing Greece: Landscape and Literature in the Periegesis of Pausanias William Hutton

The Making of Roman India Grant Parker

Hellenism in Byzantium: The Transformations of Greek Identity and the Reception of the Classical Tradition Anthony Kaldellis

Religious Identity in Late Antiquity: Greeks, Jews and Christians in Antioch Isabella Sandwell

Hellenism in Byzantium

The Transformations of Greek Identity and the Reception of the Classical Tradition

Anthony Kaldellis

CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS

Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, So Paulo

Cambridge University Press

The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB 2 8 RU , UK

Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York

www.cambridge.org

Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521876889

Anthony Kaldellis 2007

This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception

and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements,

no reproduction of any part may take place without

the written permission of Cambridge University Press.

First published in print format 2007

ISBN 978-0-511-37517-0 mobipocket

ISBN 978-0-511-37939-0 eBook (Kindle Edition)

ISBN 978-0-521-87688-9 hardback

Cambridge University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party internet websites referred to in this book, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

I dedicate this book to my uncle Christophoros, in gratitude and admiration.

Preface

This book attempts to mediate among different fields, different methodologies within those fields, and my own personal interests and backgrounds. It combines intellectual, cultural, and literary history to answer the following questions: what did it mean to be Greek in Byzantium, how and why did those meanings change over time and across different sites of the culture, and how were those changes related to the reception of the classical tradition? Obviously, its primary audience will be those who are interested in late antiquity and Byzantium, but it also attempts to build bridges to (and between) Classics and Modern Greek Studies. Classicists are increasingly looking beyond the narrow definitions of their field that prevailed in the past and into the extension and reception of Greek culture in later societies (from the Second Sophistic to late antiquity, the Renaissance, and modern Greece). This book offers them a guide to how some familiar ancient themes continued to evolve in Byzantium. Students of modern Greece, on the other hand, have long been intrigued by the way in which Greek modernity has defined itself in terms of classical antiquity, sounding alternating notes of tension and harmony, but ideologies and institutions have not favored giving the same attention to Byzantium, and nonexperts are understandably intimidated by the alien, overdocumented, and understudied millennium that stands between the two canonical poles. This book offers them a study of how the Byzantines coped with many of the same problems that the modern Greeks would face (and still do), especially regarding the contested spaces of Greek identity. My position as a Byzantinist in a classics department that includes a program of Modern Greek has proven an advantage for thinking through these fundamental questions.

Methodologically the book likewise stands in the middle. It basically tells a narrative and rests on research that is primarily philological: reading through thousands of pages of arcane and mostly untranslated sources and examining what they say. At the same time, Hellenic identity is treated as a historically and discursively constructed entity, not a stable essence, and therefore as always being reimagined and contested. This is now a conventional approach in the humanities. The parameters and modalities of identity memory, performance, polarity, rhetoric, ritual, reception, community, nationality, ethnicity, continuity, and many others have now generated a vast theoretical literature and no longer appear as straightforward as our sources wish to represent them. And to deconstruct a text is not merely to refute its truth-claims or to historicize it, but to show what parts of the world it must forget in order to have a presence and how these exclusions are often reinscribed within its basic assumptions. I have, therefore, tried to combine philological, historical, and more theoretical approaches in this study, though I have tried never to deviate from the rule that anything worth saying can be said in lucid English. Too much theory can sometimes make it impossible to say anything straightforward at all, and I have a story to tell.