Table of Contents

INTRODUCTION

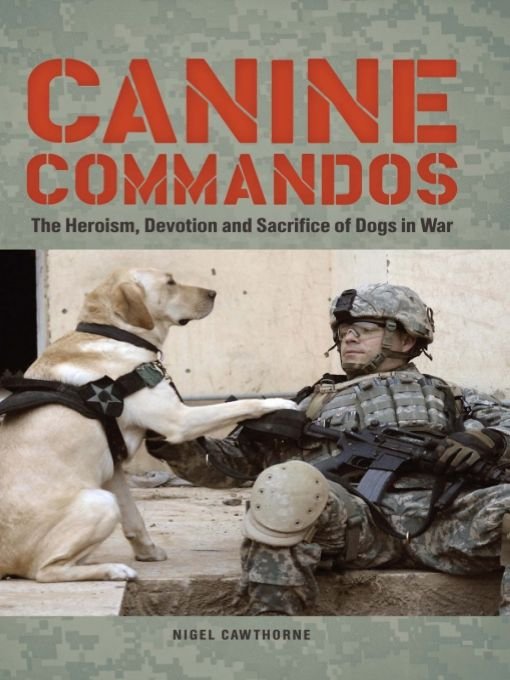

NEWS THAT A DOG NAMED CAIRO had been on the mission with SEAL Team Six to kill Osama bin Laden in May 2011 sparked interest in the contributions and the fate of war dogs. Some three hundred are put up for adoption each year at the end of their active service, and in the weeks following the death of bin Laden, more than four hundred applications were filed. But civilian adoption of war dogs was not always possible. The law allowing these adoptions was only passed in 2000. Before that, dogs were usually put down once their tours of duty were over.

After the Vietnam War, only 204 of an estimated 4,900 war dogs that served in Southeast Asia returned to the United States, according to military dog organizations. The others were euthanized, released by their handlers in an attempt to save their lives, or given to the South Vietnamese army, rendering their fate uncertain. But these days, few are put down. Most are placed in good homes. In 2010, for example, 304 were adopted, while another 34 continued service in police departments or other government agencies. Then, following the bin Laden raid, applications soared and the adoption wait time swelled to six months.

Adopting a military dog is not cheap. Their new owners often have to pay $1,000 to $2,000 to bring a dog back to the US on a commercial flight. Putting a retired dog in a crate on a military cargo flight at public expense is against military regulations because, once the dog is adopted, it no longer belongs to the military. Besides, the government has already picked up the check for the animals initial purchase, board, upkeep, and training; these costs run to between $40,000 and $50,000 per dog. Sadly, not all ex-military dogs are suitable for adoption by civilians. Some dogs that have performed prolonged service on the battlefield are not safe to be around children. Before they are released to the public, dogs are tested extensively for the symptoms of trauma. For the most part, however, those that have been encouraged to be aggressive during their period of service can be detrained, and most are remarkably docile even after being under gunfire for prolonged periods.

Generally, these dogs are more than ten years old when they retire from the military. Some may simply have been guard dogs at military establishments. Others have been on the front lines and have been credited with saving hundreds of lives. One dog in Iraq, for example, detected a fertilizer bomb on the other side of a door and alerted soldiers who were about to enter the building, preventing them all from being blown sky high. Other dogs have warned troops of the presence of the enemy, spotted booby traps or mines, tracked down a foe, discovered the bodies of the fallen so they can be returned to their loved ones, or simply been a companion in adversity.

We all know dogs that are afraid of thunder, so it comes as no surprise that many are nervous around gunfire. Other dogs feel so deeply connected to their owners and handlers that they are traumatized by human distress. But the dogs in this book are not the nervous type. They are the bravest of the brave, courageous and loyal beyond the call of duty.

War dogs do not start wars. They are not concerned with ideologies or the clash of civilizations; those are human failings. Dogs serve because they live to please human beings. We owe them a great debt.

Nigel Cawthorne

Bloomsbury

March 2012

CHAPTER ONE

WAR DOGS IN EARLY TIMES

DESCENDED FROM THE GRAY WOLF, dogs became domesticated about twelve thousand years ago. First, they were used as hunters, then as herders when sheep, goats, and cattle were domesticated alongside them. Then, as the growth of civilization led to rivalry and war, they accompanied soldiers as war dogs.

The earliest known war dogs were a type of mastiff domesticated in Tibet during the Stone Age. Their use soon spread. In the tomb of Egyptian king Tutankhamun (133323 BC), there are depictions of mastiffs with armored collars escorting the pharaohs chariot, and a decorated wooden casket shows the young king on his chariot pursuing Nubian soldiers who are being harassed by his dogs.

When the Persian king Cambyses II invaded Egypt in 525 BC, he used packs of war dogs to disrupt the Egyptian cavalry. The Greeks used fighting dogs against the Persians at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC and during the Peloponnesian War of 43104 BC. During the Corinthian War (39587 BC), soldiers in the garrison at Corinth were asleep when the Athenians landed on the coast. Fifty war dogs were kenneled along the beach; they attacked the invaders. All but one were killed. But the survivor, Sorter, raced to the citadel and roused the garrison, and the soldiers repelled the Athenians. A grateful city presented the dog with a silver collar, inscribed, To Sorter, defender and savior of Corinth.

The Romans came up against dogs when fighting the Teutons at the Battle of Versella in 101 BC. They were unleashed by the blonde-haired women of Wagenburg, according to the Roman consul Marius. The Romans learned their lesson and developed formations of attack dogs wearing spiked collars and body armor. Writing during the first century AD, Pliny the Elder said that these Roman war dogs would not even cower in front of men wielding swords. Dogs were also used on guard duty and as messengers. Attack dogs marched with the legions but, according to Julius Caesar, they met their match when they came up against the mastiffs bred in Britain when he invaded in 55 BC. When Caesar withdrew, the Romans took with them British mastiffs to breed for use in the arena.

Attila the Hun traveled with canine sentinels when he invaded Europe in the fifth century AD. Again, they were swathed in armor and chain mail. The use of dogs as weapons of war continued throughout the Dark Ages that followed the fall of Rome. A manuscript from the eleventh century says, Dogs were trained to savagely bite the enemy. They were coated with mail and carry a brazen vase on their backs, partially filled with a resinous substance, together with a sponge soaked in spirit. The horses of the enemy, thoroughly upset by the bites of these creatures and the burning fire from the vases, flee in disorder.

By the thirteenth century, Kublai Khan, it was said, had a contingent of thirty thousand Tibetan mastiffs in his army. The English knight Sir Piers Leigh of Lyme Hall, Cheshire, took his mastiff with him to war in France. When he fell wounded at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415, he was guarded throughout the night by the faithful bitch until his countrymen took him to Paris, where he died. The mastiff was taken back to England and is commemorated in a stained-glass window in Lyme Hall.

When the walled city of St. Malo in northern France declared itself an independent republic in the fifteenth century, it kept three hundred dogs at the expense of the city guard. During the sixteenth century, the Piedmontese kept packs of war dogs numbering three hundred each. Quoting the fifteenth-century Italian historian Flavio Biondo, the sixteenth-century Italian naturalist Ulisse Aldrovandi said these war dogs had a terrifying aspect and look as though they were just going to fight and be an enemy to everybody but their master; so much so that he will not allow himself to be stroked even by those he knows best, but threatens everyone alike with the fulminations of his teeth, and always looks at everybody as though he was burning with anger, and glares around in very direction with a hostile glance.