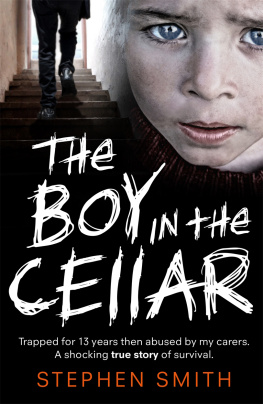

B y a curious irony, I am writing this book in a basement but this is not a House of Horrors. Twenty years ago when I moved in, I was told by my then landlord that the converted cellar in Bloomsbury, not far from the British Museum in central London, had once been the studio of the photographer David Bailey. I never checked that out in case it wasnt true and, as I was familiar with Baileys work, I would rather live with the idea that the space had once been inhabited by numerous beautiful models, frequently and pleasingly dshabill. My then landlord told me that he had bought the basement studio and converted it into five flats. Mine I have just measured it is 43 square metres. The cellar that Elisabeth Fritzl and her subterranean family lived in was, by all accounts, 35 square metres. However, the height of her ceiling was an oppressive 1.7m 5ft 6in while mine is 2.4m, a dizzying 8ft.

On the street side, my apartment is below the level of the pavement. But there is a broad walkway in between and light, especially on the sunny summer mornings while I was writing this book, comes pouring in. When the landlord was making the conversion, the council ordered him to dig out the back to allow more light in, so I have a broad patio area and bank planted, after a fashion, with greenery. I overlook this small city garden from the large French windows where I work. These let in so much sunlight that, on sunny days, I have to close the curtains so that I can see the screen of my computer. For Elisabeth Fritzl, this would have been an unimaginable inconvenience. Some days, I put garden furniture out there, open up the umbrella and work outside.

Although the floor space of my flat is comparable to that of Elisabeths cellar, after years of back-breaking excavation, I only have to share the space with one other person my son. He is 24, born less than two months after 18-year-old Elisabeth disappeared from the world of light and greenery. Although there are only the two of us, we often get on each others nerves. This is despite the fact that we have doors on our bedrooms and on the bathroom and lavatory, so we can enjoy some privacy, or lock ourselves away if we are feeling tetchy or antisocial.

While all basements suffer to some extent from damp and mould, it would be hard to imagine a place more light and airy than my apartment. I have a front-door key and can come and go as I please. Friends, relatives and lovers come round. But despite all these advantages, some days, when I have been working hard at home, I feel a twinge of cabin fever. Come evening time, I need to go out to the restaurant next door, to the swimming pool and steam room in the hotel at the end of the road, or to the pub in the square, just for a change of scenery and some company and conversation. More than a couple of days without some contact with the outside world and I would go stir-crazy.

Consequently, I find it hard to put myself in Elisabeths shoes. Our lives could not be more different. Her tyrannical father stole her life between the ages of 18 and 42 the years that most people would consider the best of part of their lives. These are the years when most people have adventures, love affairs and indulge in youthful indiscretions that, though they blush about them in middle age, they would not have missed for the world.

That is certainly true in my case. Between 18 and 42, I travelled much of the world. I had written for newspapers and magazines in the UK and USA, had a handful of books to my name, been married, divorced and returned to a life of philandering, appeared in the dock of the Old Bailey for a youthful indiscretion I was acquitted, I might add and testified to a US Senate Select Committee.

For Elisabeth Fritzl, these same precious years were stolen from her by the one man who ought to love and protect her, who should have allowed her the follies of youth and been there to rescue her, if and when things went wrong. While her father pretended that he was keeping her safe from the dangers of the modern world, he was merely indulging his own selfish lust. Not only did he rob her of her life and freedom, he subjected her to an unimaginable hell of torture, physical violence, intimidation and sexual humiliation.

He then inflicted this hell on three of the children he sired by her. There are not the words to condemn this man, nor is there any sufficient punishment for what he has done, but this book is not only about the depths of cruelty and vice a man can descend to, it is also a tale of courage. This young woman somehow endured everything her vile tormentor put her through. She suffered years of solitary confinement in the certain knowledge that no one was looking for her or even imagined her fate. With no possibility of escape, the only company she could hope for was her jailer, who would most likely be visiting to rape her once again. Her only contact with the outside world was a man without a scintilla of pity or compassion.

She faced the terrifying prospect of giving birth alone. And, when the children came, she helped extend her own jail, digging out new rooms with her bare hands. She was also forced to relinquish some of those children. But the ones she kept, she did her best to rear and educate, given the appalling circumstances in which they found themselves. She did not go mad an astonishing achievement in itself. Somehow, she found the strength to remain sane. And when the opportunity came to free herself and her children, she succeeded.

By any standard, Elisabeth Fritzl is a remarkable woman. Her ordeal is over, but lets not forget about her brutal tormentor. He will die in prison or in mental hospital. There is no retribution that he can make or be forced to make, no recompense for what he has done. Instead, let us hope that the world can find some way to give this young woman and her children every pleasure and fulfilment life offers.

Meanwhile, the world must atone. The people of Elisabeths home town of Amstetten and the Austrian authorities failed to notice that she was physically and sexually abused as a child. And when she disappeared, they did not ask the questions necessary to rescue her and thwart her fathers evil plan.

Around the world, there have been some who have attempted to prove that, after a number of high-profile cases, the imprisonment and abuse of children is a uniquely Austrian phenomenon tied to that countrys Nazi past. Of course, history is a factor, but the abuse of children is not a problem exclusive to Austria. In Britain and America and just about every other country there are numerous cases of children being abused or neglected, actions that could have been prevented by the vigilance of neighbours and friends. Sadly, too many of us end up looking the other way.

Nigel Cawthorne

Bloomsbury, July 2008

I n 1984, two weeks after the end of the Olympic Games in Los Angeles, a young woman in a small town in Austria was drugged, dragged into a cellar and repeatedly raped by her own father. This ordeal would not just go on for one day, or one week, but 8,516 days just a few months short of 24 years. In all that time, she would not see natural light or breathe fresh air. With the exception of her father her jailer no one knew what had happened to her.

And while Elisabeth Fritzl languished in her purpose-built dungeon, the global events of the end of the 20th century inexorably rolled by: the IRA bombing; the Tory conference in Brighton; the assassination of Indira Gandhi; Ronald Reagans second term; Bhopal; the Sinclair C5; Gorbachev announcing glasnost and perestroika; the end of the British miners strike; Live Aid; Boris Becker winning Wimbledon; the race riots on Broadwater Farm Estate; the explosion of the space shuttle Challenger; Chernobyl; the election of former UN General-Secretary Kurt Waldheim, president of Austria, and the revelation of his Nazi past; Argentinas hand of God victory in the World Cup; the marriage of Prince Andrew and Sarah Ferguson; the City of Londons Big Bang; the AIDS Dont Die of Ignorance campaign;