Table of Contents

FOREWORD

It is difficult to write a book on a subject as complex as Josef FritzI. And certainly many Austrians would prefer that such a book not be published. In Austria there is little appetite to understand his crimes, and even less inclination to uncover the many factors that may have allowed for them to happen.

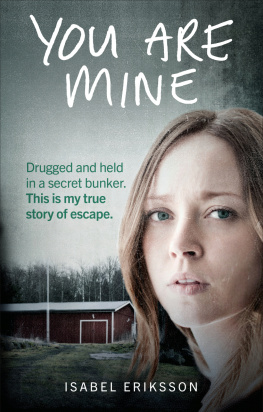

When the Fritzl case first came to light in April 2008, Austria became the unwilling focus of massive media scrutiny. Not only were the gravity and range of his crimes against his children unparalleled in recent history, but the case had emerged only two years after a strikingly similar one, also in Austria: In 2006, eighteen-year-old Natascha Kampusch had escaped another purpose-built dungeon where she had been forced to live since age ten by an electrical engineer who had abducted her. When the Kampusch case came to light, it was regarded by most people as a unique case. But suddenly there was Josef Fritzl, and another cellar, and yet another story of prolonged incarceration and sexual abuse.

And although the police and social services in Amstetten have always declared themselves satisfied that the crimes of Josef Fritzl were unpreventable, his sentencing to life imprisonment in March 2009 left many important questions unanswered regarding the role of the authorities. His trial lasted less than four days, and neither the court nor the Austrian media seemed inclined to get to the bottom of how Fritzl could have committed such terrible deeds for so long. There was no investigation into the role of the authorities, there has not been a single resignation, and it was never determined whether there might have been any possible negligence on behalf of the officials who had come to know the Fritzls over the years. Experts from Scotland Yard expressed astonishment that many of Fritzls family members were never questioned by police in detail or in a manner fit for cases of such complexity. Many observers strongly suspected that this crime could have been stopped in its tracks many times. The feeling was that justice had not been served. Meanwhile, not only the Amstetten authorities but also those high up in the Austrian government would continue to hold that they bore no responsibility for what happened for so many years to Elisabeth Fritzl and her children.

But there is another side of this story, one that has been equally neglected and one to which we hope to give justice in this book. Most people who have read about the Fritzl case have asked themselves how Elisabeth Fritzl survived her twenty-four-year incarceration. And yet she has emerged from a lifetime of unimaginable deprivation and terror as a heroic figurea woman who, though her means were few and the fear in the cellar was great, protected her children against their father. Often, in so doing, she acted against her own interests. Over the years, Elisabeth Fritzl did everything she could to ensure the safety of her children and strove to give them some semblance of comfort and normality in the cellar: She educated them, she often persuaded her father to bring down sufficient food to ensure their survival, and she emerged from the cellar undiminished by the many years of imprisonment. Indeed, the most extraordinary aspect of this case is not the fact that Josef Fritzl was able to incarcerate his daughter for almost two and a half decades; it is Elisabeth Fritzl herself. In this book, we hope to shed some light on her astonishing courage and the incredible ability of the human spirit to overcome seemingly impossible conditions.

In the course of researching this book we have spoken to many people who knew Josef Fritzl personally or were friends of the Fritzl family, as well as many of those who were directly involved in the case when it came to light: police, psychiatrists, doctors, and lawyers. Many of them expressed to us their wish that the intricate facts of the case be laid bare in a way that they will never be in Austria. Although we have endeavoured to name our sources where possible, several of the interviews that we were granted by those involved in the case had to be conducted under conditions of anonymity. We are grateful to the people who chose to speak out about this case and to explain to us its intricacies, despite, in some instances, considerable pressure from above.

Finally, much has been written in the press about the effect on Josef Fritzl of his wartime childhood. And although Fritzl himself has sought to blame the evolution of his double life on the Nazi Austria of the late 1930s and early 1940s, this claim cannot be taken seriously. What is undoubtable, however, is that still now, Austria itself has yet to face its past or analyse with any seriousness its impact on the present. As a result there continues to exist in Austria a culture of looking away, a squeamishness about examining in any depth the harsh truths about its society, and a distaste for self-analysis. We believe that Josef Fritzls crimes were largely preventable, had the authorities been prepared to acknowledge the many clues laid before them over the years, and that Elisabeths fate in her fathers cellar was not inevitable, as at least one member of the Austrian government has suggested. We hope that this book, in addressing the circumstances of the Fritzl case; by examining his behavior and descent into inhumanity, piece by piece; and by flagging the signsboth subtle and blatantof his extreme cruelty, will in some way help illustrate how important it is to look.

PROLOGUE

Dr. Albert Reiters habit was to check on his patients for a couple of hours on a Saturday morning. So by 7:15 A.M. on Saturday, April 19, 2008, he was already making the seven-minute drive to Amstetten Hospital. Hed had a coffee instead of breakfast at home, and now he lit a cigarette.

At 7:30 A.M. he was in the elevator up to the second floor: the intensive care unit of which he was the head.

As usual he stopped off in the staff room to discuss any problems that might have occurred among the patients overnight. There had been none, and Reiter was soon making his way through the series of noiseless, code-accessed automatic doors, past the calm and well-administered horseshoe-shaped reception areathe departments nucleusand to each of the units eight beds, distributed among two single and three double rooms. To help make the patients experience as comfortable as possible, framed photographs of trees and flowing streams had been hung on the walls, and a sign, hand-painted on a door panel by some of the nurses, read Waking-up Room in cheerful rainbow colours. Reiter moved from bed to bed, each one flanked by its vast panel of elaborate, lifesaving equipment on one side and a large window on the other. On Reiters instructions, every bed space had been designed to have access to plenty of natural light from the south-facing windows that looked onto the hospital parking lot below. Beyond the parking lot, Reiter saw that it was becoming a magnificent spring day.

It was getting toward 8:30 A.M. when a call came through from the hospitals accident and emergency room: Paramedics had just brought in a critically ill young woman. Reiter sent down a junior doctor to look at the case. Five minutes later he joined him.

The girl was unconscious.

Laid out on a stretcher, she looked no more than twenty and was clearly terribly sick. Even Reiters first glance told him that she was very close to death. Her name, Reiter was told, was Kerstin.