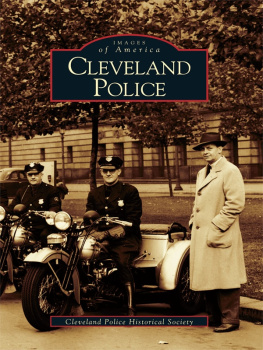

W hen the news broke that three women had been held captive for over ten years in Cleveland, Ohio, the world was shocked. It seemed unbelievable that they could have been kept prisoner in a seemingly normal house by a man well known in the community just a few blocks from where they had disappeared. Neighbours and friends had spotted nothing and no one suspected their captor, Ariel Castro, of being a depraved monster who used the young girls as sex slaves while simultaneously maltreating and torturing them.

Sadly, America and the world had been shocked before. How could Jaycee Lee Dugard have been held for 18 years in the back garden of convicted sex offender David Garrido in a small town in California? How could Tanya Nicole Kach be held in the bedroom of her school security guard in his parents home in a suburb of Pennsylvania for ten years without anyone noticing? And how could Colleen Stan be kept in a box under the bed of a couple in Red Bluff, California, who only brought her out to humiliate, torture and rape her?

Back in the 1980s, Gary Heidnik established a basement baby farm in his home in Philadelphia where he beat, tortured and raped six women, one of whom he tortured to death. Then there was John Jamelske who held five women as sex slaves, one after another, over 15 years before he was caught.

The world was equally shocked when Elisabeth Fritzl emerged from the cellar of the family home in Austria after 24 years and having given birth to eight children sired by her own father. This came less than two years after another Austrian girl named Natascha Kampusch emerged after 3,096 days in captivity in a cellar. It was followed by the case of what the newspapers dubbed the British Fritzl, who kept his daughters isolated by moving frequently while fathering seven children by them.

In Belgium, two young girls were found in the cellar of convicted child molester Marc Dutroux, sparking a political scandal that reached the highest levels of society. Even in Russia, a former army officer put two girls in a cellar to rape them and impregnate them.

But those who disappear from the streets are not only held for sex. While the Cleveland case was unravelling, it was discovered that four men were being held in Houston for their social security cheques. In Britain, a handful of men were held for up to 15 years by a family who forced them to work while holding them in the most squalid conditions.

But this book is not about the monsters who thrive on the misery of others. The Disappeared is about the bravery of the survivors particularly the women who endured the unendurable and came out fighting. Often, they have simply outsmarted their captors who somehow imagined that they were intellectually superior to their victims. While the perpetrators demonstrate the extreme depths of depravity to which human beings can sink, the survivors show the heights of courage attainable by the human spirit.

O n Monday, 6 May 2013, Ariel Castro left his house at 2207 Seymour Avenue, Cleveland, Ohio. It was a three-storey clapboard building with a detached garage, standing in the middle of a tree-lined street in Clevelands West Side neighbourhood a working-class area with a close-knit community. Ariel Castro had bought the four-bedroom house from Edwin and Antonia Castro in 1992 for $12,000 (7,750). It was now valued at $36,100 (23,300), but faced repossession over the non-payment of taxes. Castro owed some $2,501 (1,615) in taxes for the period 201012. The property had four bedrooms, a bathroom, a 760sq ft (71sq m) basement, two porches and an attic. It is just steps away from a petrol station and a Caribbean grocery. Other than being a bit run down, there was nothing at all extraordinary about it except that it held a terrible secret.

Ariel Castros son Anthony had visited the house just two weeks before and noticed that the doors to the basement, the attic and the garage were padlocked. He had spent his early years in this house, but most of the rooms were off limits even to family members. Ariel Castros ex-wife, Grimilda Nilda Figueroa, Anthony and his three sisters moved out of the house in 1996 after years of violent abuse. Since then, Anthony seldom visited.

The house was always locked, recalled Anthony. There were places we could never go. There were locks on the basement locks on the attic locks on the garage.

In fact, on that visit Anthony had not even been invited inside. Visits, when he made them, were brief. I havent been at that house for longer than 20 minutes for longer than I can remember, he said. And were talking since high school. Late nineties.

To the neighbours, Ariel Castro, a school bus driver, was just a regular Joe who chatted with other families on their porches, waved hello in the street and invited neighbours to clubs where he played bass with several Latin bands. He was not a troublemaker, said 58-year-old Jovita Marti, whose mother lived across the street.

Mike Kazimore, a local postman who delivered mail to the porch virtually every day for the previous 12 years, said, It looked like a normal house.

Niki Greiner, another resident, said the property was usually quiet, although sometimes you would hear music. This broke the background hum of traffic, but was rarely loud enough to obscure the birdsong.

Some of the houses in the street had seen better days. The recession had taken its toll and paint peeled from a fair few of the one-and two-storey houses. As in many of the poorer areas of American cities, a number of houses had been boarded up since the sub-prime mortgage crash. But it was not the kind of area where you felt menace on the streets. The people were friendly and happy to talk; residents like to sit out on their porches in the warm weather and watch the world go by, and the red-brick Immanuel Evangelical Lutheran Church with a large silver cross on the wall was well attended.

Ariel Castro had left home to visit his mothers house nearby that afternoon. He arrived at around 4.30pm. Other members of the family were there and he greeted them warmly. The first thing he said was, Familia! said his 63-year-old brother-in-law, Juan Alicea.

After a meal of rice and beans and pork chops, Castro and Alicea did some digging in the garden with Aliceas two grandchildren. He was talking about how he wanted to get it done because he didnt want to have to come back and do it tomorrow, said Alicea. Then he kissed his mom goodbye and said, I love you, Mom. The food was good. Just like normal.

But that day was not like normal. When he left the house, Castro had forgotten to lock the front door. Inside was 27-year-old Amanda Berry, one of three who had been held as a slave there for over a decade. All that stood between her and freedom was a flimsy storm door, but she was afraid to break it open because she thought that Castro might be testing her. Castro used a sick game to intimidate his captives; he would pretend to leave the door unlocked and beat them if they tried to escape.

This time, though, she plucked up all her courage and started screaming. Her cries alerted a neighbour, restaurant pot-washer Charles Ramsey, who was eating a hamburger.

He had spoken to Castro early that day. It was at around 3.00pm when Ramsey handed Castro his mail, which had been put in the wrong mailbox. He had seen Castro leave the house. Then Ramsey had got on his bike and cycled around to the local McDonalds. After he got back, he was in the living room by the front door when he heard Amandas cries for help.

Man, this girl screamed like a car had hit a kid, which made me, you know, stop eating. What the hell was that? said Ramsey. You know, so when I got up, I saw this my neighbour across the street, he run across the street and Im like Im thinking, where you going, because aint nobody next door because I just saw Ariel leave.