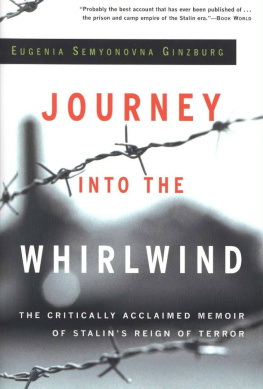

Exiled to Stalins Prisons

Exiled to Stalins Prisons

Albert Pleysier and Alexey Vinogradov

Hamilton Books

Lanham Boulder New York Toronto London

Published by Hamilton Books

An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

Hamilton Books Acquisitions Department (301) 459-3366

6 Tinworth Street, London SE11 5AL

Copyright 2019 by The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018958295

ISBN: 978-0-7618-7091-3 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN: 978-0-7618-7039-5 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN: 978-0-7618-7040-1 (electronic)

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

Acknowledgments

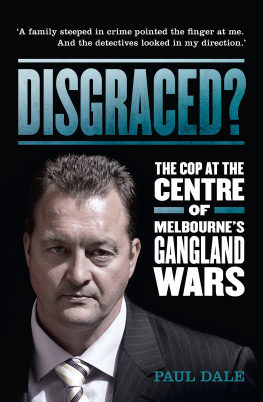

The drawing on the cover of the book is of a female Soviet citizen who is being transported by train to one of Joseph Stalins prison labor camps. The authors wish to thank the artist, Jane Pleysier, for permission to use the drawing.

The authors also wish to thank David Price for creating the map of Soviet Russia included in the book.

The author, Albert Pleysier, dedicates the book to his Heavenly Father.

Introduction

Why have I been exiled to prison? It was a question millions of Soviet citizens asked themselves in the latter 1930s and in the years that followed the Great Patriotic War. The charges brought against those who were imprisoned were decided by the State and the time of incarceration was also decided by the State. Urkho Rukhanen was arrested in 1938 and was accused of participating in an anti-Soviet nationalist organization. The accusation was a fabrication. Urkho was declared guilty, was exiled to a prison labor camp and was released in 1946. Sofia Prupis was arrested in 1949. She was accused of being a Trotskyite and a Zionist. The charges brought against her were fabrications. She was declared guilty of treason and given a ten-year prison sentence. Both Urkho and Sofia are the main subjects in the book.

In the mid-1930s Joseph Stalin became concerned that enemies outside the Soviet Union would use ethnic minorities within the Soviet Union to undermine socialism and the political leadership of the Soviet Union. Thus, Stalin initiated the national operations directed against ethnic groups from Afghanistan, Bulgaria, China, Estonia, Greece, Iran, Germany, Poland, Korea, Kurdistan, Latvia, Macedonia, Romania and Finland. By the time national operations ended in 1938, almost 350,000 people from these ethnic groups had been arrested of whom more than 247,000 were executed. More than 88,000 were held in local prisons or were sent to prison labor camps in remote areas within the Soviet Union. Urkho Rukhanen was an ethnic Finn and he was among the thousands of victims that were sent to a prison labor camp. Urkho was declared guilty of participating in an anti-Soviet nationalist organization and was sentenced to five years of imprisonment. The charge that the State brought against Urkho was a fabrication. Urkhos story is recorded in chapter two of the book.

Trumped-up charges were also brought against Sofia Prupis in 1949. She had refused to denounce a professor at Leningrad State University where Sofia worked as an assistant lecturer. The professor was accused of being a cosmopolitan and in 1946 Stalin had begun a campaign against cosmopolitanism. Upon Sofias arrest, she was charged with being a Trotskyite, a charge used often against people who were viewed as enemies of the State. Because Sofia was a Jew, she was also accused of being a political Zionist. Sofia was declared guilty of treason and given a ten-year prison sentence under Article 58 paragraph 10 within the Criminal Code of the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic. Sofias story is recorded in chapters four through eight of the book.

Source: Drawn and designed by David Price.

Chapter 1

Stalins Campaign

against the Soviet Finns

In 1923 the government of the Soviet Union officially adopted at the Twelfth Party Conference a policy known as Korenzatisiia (nativization). Under Korenzatisiia the Soviet government actively sought to promote the cultural development of non-Russian nationalities and to encourage their political participation in the Communist Party and the Soviet government.

In 1933 there were two Finnish national raions, Lembolov and Nicholas, within the Leningrad Province. (A raion was the smallest territorial unit in the Soviet Union above the village.) Finnish, not Russian, was the official language of the two raions in the Leningrad Province. There also existed in Leningrad Province 284 Finnish elementary schools, a Finnish pedagogical institute in the city of Leningrad and 434 Finnish collective farms throughout the province. The Soviet government also made, in the province, Finnish language radio broadcasts.

In the mid 1930s, Joseph Stalin terminated Korenzatisiia in favor of a more Russian-centered nationality policy. Stalin believed that many of the nationality groups in the Soviet Union were inherently disloyal to the Soviet state. These groups fell into two major categories. One category consisted of nationalities indigenous to Russia. It included the Karachays, Kalmyks, Chechens, Ingush, Balkars and Crimean Tartars. The other category consisted of nationality groups that had emigrated to Russia or the Soviet Union from other countries. These nationality groups had ethnic and cultural ties with states outside of the Soviet Union. Stalin feared that the nationality groups were filled with potential spies and saboteurs awaiting orders from their ethnic homelands. Thus, Stalin initiated the national operations directed against ethnic groups such as the Soviet Koreans, Greeks, Meskhetian Turks, Khemshils, Kurds, Germans and Finns.

Stalin initiated a series of repressive measures against the Soviet Finns beginning in 1935. He wanted to secure the border regions of the Soviet Union with Finland and Estonia by creating military zones from which all non-Russians would be expelled on grounds that they were politically unreliable. On March 25, 1935, Genrikh Yagoda, head of the NKVD, (see Glossary- Soviet secret police) reported on the proposed removal of anti-Soviet elements from Karelia and the Leningrad Province.

In 1937, Stalins regime abolished the Finnish national raions in the Leningrad Province. The cultural institutions within these raions did not survive long without administrative support. Between 1937 and 1938 Stalins government shut down all of the Finnish-language publishing houses, the schools administered in Finnish, the Finnish-language radio broadcasts and the churches in which worship services were conducted in the Finnish language.

In 1938, the regime of Stalin took action against spies and diversionists. The State viewed anybody with a foreign sounding name as a potential spy or a diversionist. On January 31, 1938, Nikolai Yezhov issued a memorandum to the Central Committee of the Communist Party regarding a Politburo decision which was to extend, until April 18, 1938, a NKVD operation to neutralize spies and diversionists. (Yezhov, at this time, was the head of the NKVD. Earlier, on September 25, 1936, Stalin had sent a telegram from Sochi to Moscow informing the members of the Politburo that Yagoda was to be removed as head of the NKVD. The man who would take his place was Yezhov.)

Next page

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.