Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the Print Version

PRAISE FOR Whats Prison For?

Americas unjust system of mass incarceration tears families apart, costs taxpayers billions of dollars each year, and doesnt make our communities any safer. Bill Keller has been shining a light at our broken criminal justice system for years, and powerfully argues that America can and must do better. To do nothing or say nothing only reinforces the current nightmare. I hope you read this book, learn, and in some way, join the growing bipartisan efforts to bring about urgently needed change.

SENATOR CORY BOOKER

A learned, lucid primer on the American prison systemits history and particularly on the best ideas for reforming it. Broadly sourced, intelligently curated, wisely explained.

TED CONOVER,

author of Newjack: Guarding Sing Sing

Whats Prison For?

Punishment and Rehabilitation in the Age of Mass Incarceration

Bill Keller

COLUMBIA GLOBAL REPORTS NEW YORK

Whats Prison For?

Punishment and Rehabilitation in the Age of Mass Incarceration

Copyright 2022 by Bill Keller

All rights reserved

Published by Columbia Global Reports

91 Claremont Avenue, Suite 515

New York, NY 10027

globalreports.columbia.edu

facebook.com/columbiaglobalreports

@columbiaGR

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Keller, Bill, author.

Title: Whats prison for? : punishment and rehabilitation in the age of mass incarceration / Bill Keller.

Description: New York, NY : Columbia Global Reports, [2022] | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022014399 (print) | LCCN 2022014400 (ebook) | ISBN 9781735913742 (paperback) | ISBN 9781735913759 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Prisons. | Imprisonment. | Criminals--Rehabilitation.

Classification: LCC HV8665 .K45 2022 (print) | LCC HV8665 (ebook) | DDC 365--dc23/eng/20220513

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022014399

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022014400

ISBN: 978-1-7359137-5-9 (ebook)

ISBN: 978-1-7359137-4-2 (paperback)

Book design by Strick&Williams

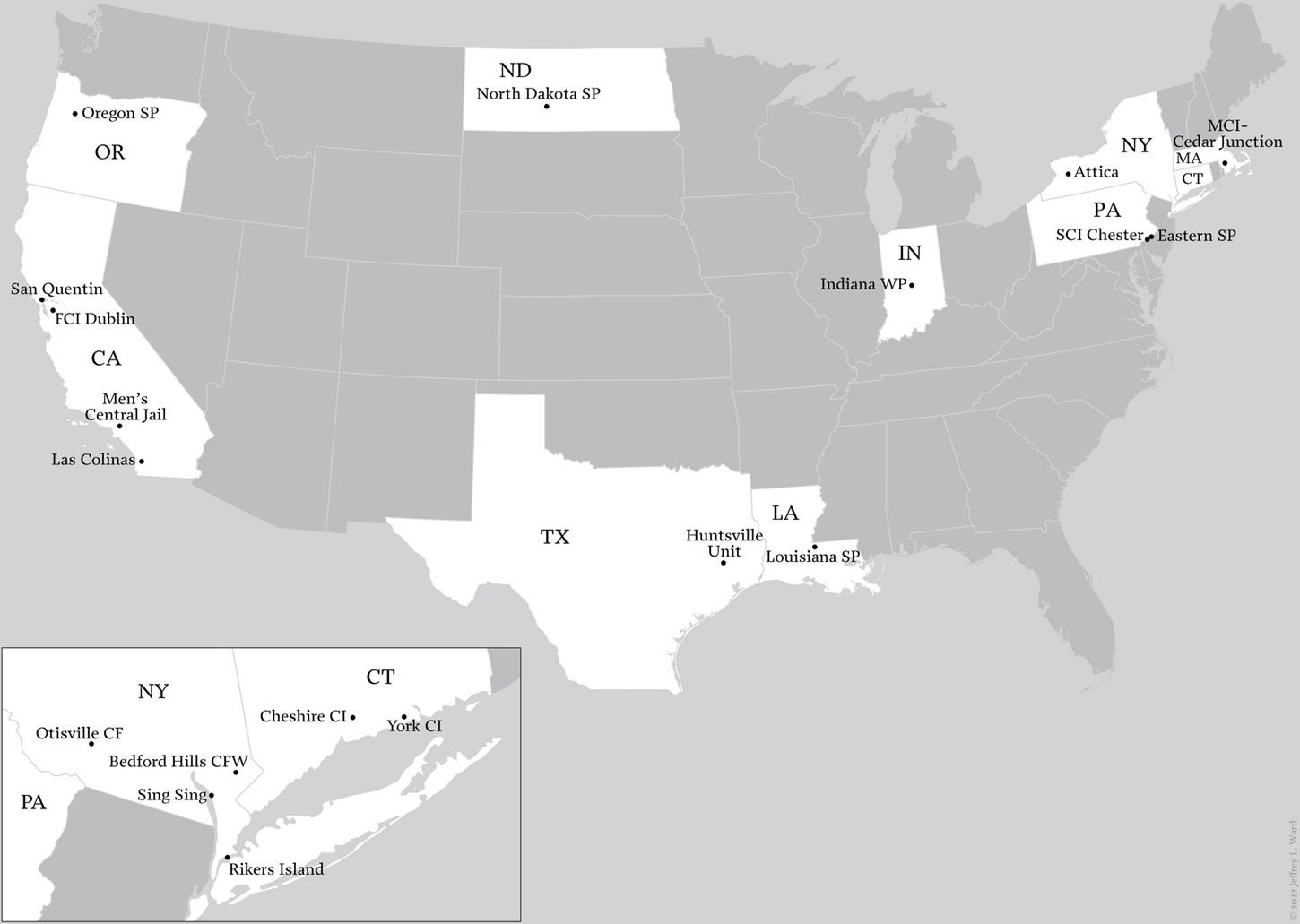

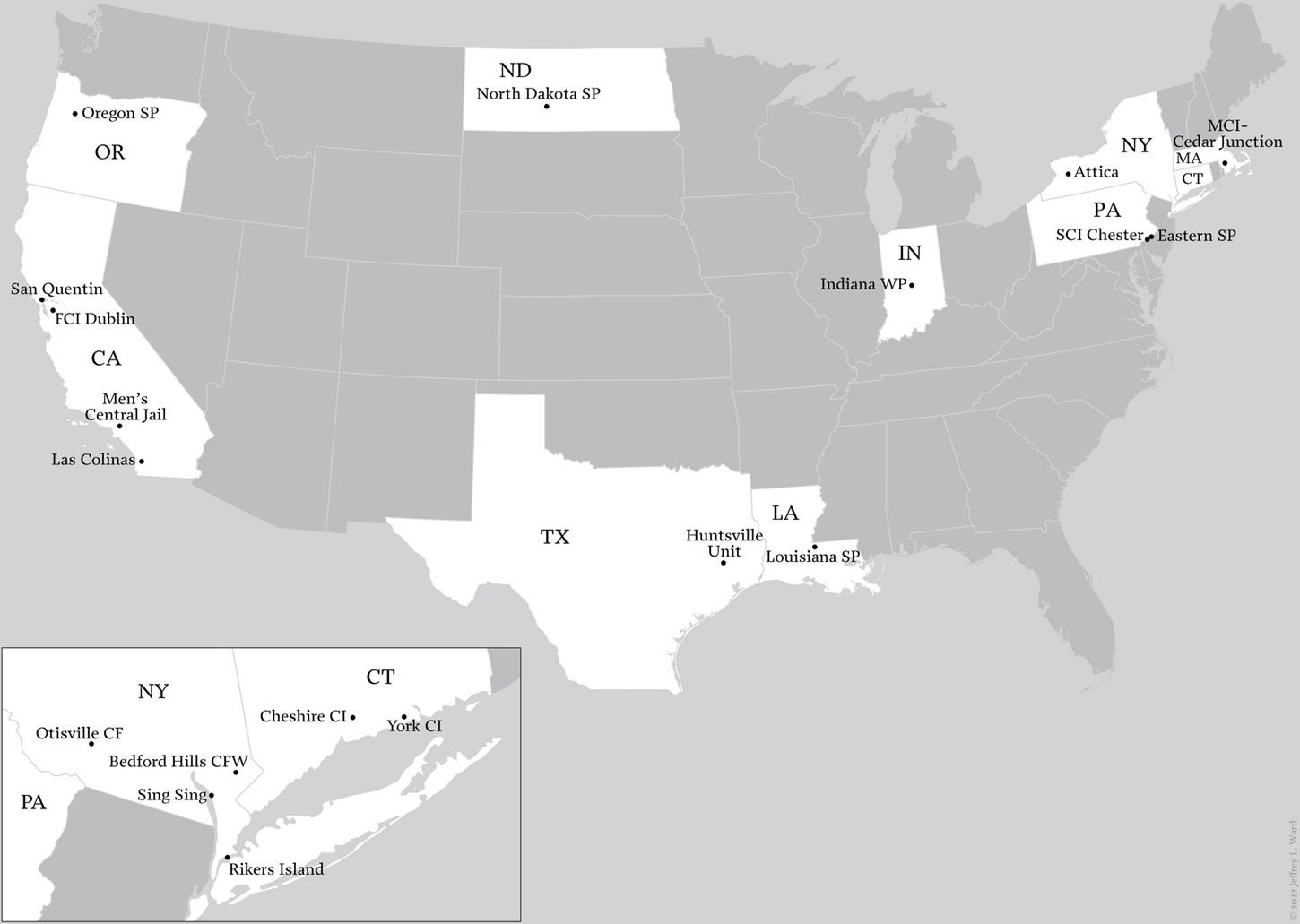

Map design by Jeffrey L. Ward

Author photograph by Emma Keller

Printed in the United States of America

While society in the United States gives the example of the most extended liberty, the prisons of the same country offer the spectacle of the most complete despotism.

ALEXIS DE TOCQUEVILLE AND GUSTAVE DE BEAUMONT

On the Penitentiary System in the United States and Its Application to France, 1833

CONTENTS

Introduction

In early 2014, I was invited to breakfast by Neil Barsky, a journalist turned investor turned philanthropist, who had an audacious proposition. At a time when news outlets were struggling to stay afloat, Neil planned to start a new one: a nonprofit newsroom focused on our broken criminal justice system. The Marshall Project, which he named for the civil rights giant and Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, would assemble an independent team of reporters and editors to investigate the causes and consequences of mass incarceration. To maximize its impact, it would share the work with other news organizations. He was looking for an editor in chief.

Id spent thirty years at the New York Times as a correspondent, editor, and, most recently, op-ed columnist, but had never covered criminal justice, unless you count a few months long ago on the night cops beat for the Oregonian. So, before accepting Neils offer, I did a little reporting, which marked the beginning of an education that continues to this day.

My crash course in criminal justice taught me that this country imprisons people more copiously than almost any other place on Earth. Some countries, notably including China and North Korea, do not fully disclose their prison populations, so America may not actually hold the dubious distinction of first place. But there is ample justification for calling what we do in America mass incarceration. Our incarceration rate per 100,000 population, which includes adults serving time in state and federal prisons and those awaiting trial or doing short time in county jails, is roughly twice that of Russias and Irans, four times that of Mexicos, five times Englands, six times Canadas, nine times Germanys, and seventeen times Japans. Our captive population is disproportionately Black and brown.

Much of the public debate was focused on the mass in mass incarceration, a growing consensus that we lock up too many people for too long. There was also considerable agreement on how to reduce the incarcerated populationif we can muster the political will. We can make some relatively minor crimesstarting with low-level drug offensesnon-crimes. We can divert people to mental health and addiction programs, or probation or community service. We can abolish mandatory minimum sentences and encourage prosecutors and judges to apply the least severe punishment appropriate under the circumstances. We can raise the age at which accused youngsters are subject to adult punishment. We can give compassionate release to old and infirm inmates who are unlikely to pose a danger. We can reduce the use of cash bail, which traps the poor in the modern equivalent of debtors prison.

In fact, the incarcerated population in this country has been in a gradual but steady decline since a peak in 2008from 2.3 million to 1.8 million in 2020, according to data compiled by the Vera Institute of Justice. That includes an unprecedented 14 percent drop in 2020, attributed in part to early releases and locked-down courts during the coronavirus pandemic.

States have demonstrated that they can cut prison populations without jeopardizing safety. In the decade ending in 2017, thirty-four states, red and blue, simultaneously reduced incarceration and crime rates. Addressing the mass could also mean prisoners left behind would be less subject to overcrowding, which contributes to explosive violence and, as the 2020 plague year demonstrated, leaves prisons more vulnerable to rampant contagion.

This book examines the incarceration part of mass incarceration. Our prisons are not the most transparent institutions, and out of sight too often means out of mind. But the American way of incarceration is a shameful waste of lives and money, feeding a pathological cycle of poverty, community dysfunction, crime, and hopelessness. What is the alternative? Can we use our prisons to improve the chances that those caught in the criminal justice system emergeand upward of 95 percent of them will emergewith some hope of productive lives?

For more than two hundred years, there has been a tension between a punitive streak and a faith in rehabilitation, between treating prisoners as incorrigible Others to be incapacitated and shamed and, alternatively, viewing them as capable of restoration, even redemption. Opinions about how we should use prisons have ranged from the mean-spirited no-frills prison movement of the 1990s, which proposed to take away such amenities as television and hot meals, to, at the other end of the spectrum, calls for abolishing prisons altogether.

Assuming that outright abolition is not in our near future, what kind of incarceration do we want for those were not yet ready to set free? Whats prison for?