Daughters

of

Chivalry

The Forgotten Children of Edward I

KELCEY WILSON-LEE

For my parents.

Contents

List of Illustrations

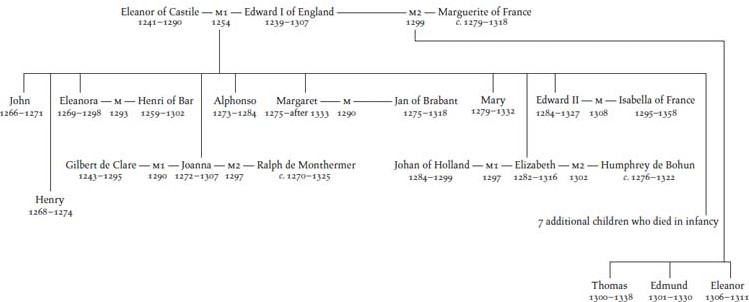

Family Tree

Introduction

C lose your eyes and think of a medieval princess. Do you see a woman clothed in vibrant silks and rich velvets, her head, hands, and waist girdled with gleaming gold and sparkling gemstones? Is she sitting at a table creaking under the weight of exotic foods, with precious wines spilling from silver vessels onto fine linens, against a backdrop of tapestries woven with romantic heroes and heroines, or in a painted hall, heraldic banners fluttering behind proclaiming her royal status and connections? Or is she riding a magnificent horse through a forest with a hunt? Or travelling from one luxurious palace to the next in a decorated carriage, stopping to preside over jousting tournaments from raised pavilions or to add lustre to the dais at major feasts and festivals? Despite the richness of her surroundings, in your mind is she ultimately a mere pawn to be traded for the political gain of her father? Are her concerns confined to the beauty of the trinkets that surround her? Is she acquiescent, a person whom the most important things happen to or for, rather than an actor in her own right?

There is no doubt that stories of medieval princesses that have built an empire of fairy stories, Hollywood films, theme parks, and cheaply produced ball gowns, all offer a vision of maidenhood focused on passive virtue. Medieval castles promote visits to princess towers, reinforcing the link between royal women in history and their powerless fictional counterparts, locked inside or frozen in deathless sleep, condemned simply to wait their eventual reward, marriage to a male saviour. It is a vision that real medieval princesses would not have recognized in their lives.

Between the end of the Middle Ages (which, depending on whom you ask, occurred in England in the quarter century or so before or after 1500) and the mid-nineteenth century, no one cared much about princesses. History was the preserve of Great Men: kings and bishops, conquerors and tyrants. And even the popular fictional heroines from the dawn of the novel Fanny Burneys Evelina, Thackerays Becky Sharp, or Austens many wonderful women were isolated from power, confined to the lower rungs of the county gentry or the middle classes. Then, in 1837, an eighteen-year-old girl raised in England became Queen Regnant, the first woman to rule her country since Queen Annes reign, more than one-hundred-and-twenty years earlier. The countless ways in which Victoria and her long reign shaped Britain, its society, and ultimately its empire have long captured public imagination. How her rule and the lives of her five princess daughters prompted a popular interest in royal women is also of immense significance. The first volume in a pioneering study of medieval women, Lives of the Queens of England, was published three years after Victoria came to the throne, written by Agnes Strickland, a poet who undertook research in partnership with her sister, Elizabeth. In the decade that followed, the historian Mary Anne Everett Green published Letters of Royal and Illustrious Ladies of Great Britain that for the first time gave a voice to medieval and early modern noblewomen. Her subsequent six-volume masterpiece Lives of the Princesses of England, from the Norman Conquest used her command of Latin and medieval French, and her access to original manuscripts, letters, and charters, to construct short biographies of every princess between the reigns of William the Conqueror and Victoria. It remains one of the outstanding achievements of nineteenth-century biography.

Across Europe at this time, as nations emerged from the Industrial Revolution, many of them developed an increasingly romanticized interest in their own histories and native mythologies, seeking connection to a pastoral, pre-industrialized past. In England, this led not only to a widespread interest in the lives of long-dead queens and princesses, but also in other aspects of the Middle Ages. Art and architecture began to feature distinctly medieval elements, such as the Gothic Revival Palace of Westminster and literary works such as Alfred Lord Tennysons poem Idylls of the King, which converted the ancient myth of King Arthur and his court at Camelot into a national epic. And paintings and stained glass panels by the artists known as the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and their followers depicted scenes from medieval romances and folktales Guinevere and the Lady of the Lake, Fair Rosamund, and Isolde that brought these old stories to new audiences that were hungry to understand what set England apart from other nations.

The romanticizing tendency of mostly male Victorian historians made it easy for genuine historical figures such as Fair Rosamund Clifford and the royal women that Strickland and Green wrote about to be melded in popular imagination alongside fictional heroines. Together with the Guineveres and Isoldes of medieval romance, the passive princesses of the fairy tales compiled by the German brothers Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm whose works were translated into nineteen separate English editions during Victorias reign became so well known that they created an expectation that real princesses would conform to these models. It was a pattern perfectly constructed for the burgeoning Victorian middle class, for whom a wife kept at home, safe from the tawdry bustle of the city and the labour market, was a mark of success; they took these newly idealized visions of princesses found in poems and artworks acquiescent, serene beauties and held them up as prime examples of womanhood.

In many ways, we have failed to move on from the vision of the medieval past that we inherited from the Victorian era. Most of us, when we hear the word princess, still imagine a damsel trapped in a tower like the eponymous heroine of Tennysons Lady of Shalott. Loosely based on the medieval Arthurian tale of Elaine of Astolat, Tennysons maiden lives full royally apparelled, sleeping on a velvet bed with a garland of pearls encircling her head. Despite the luxury of her chamber, all is not well: she lives alone in a tower encircled by a fence of thorny roses and, though the people passing hear her chanting cheerly / Like an angel, singing clearly, they never visit. Inside the tower, the Lady is entranced; forbidden by an unspoken curse from looking directly at the beauty of the world and Camelot, she must instead continually weave a tapestry depicting its glory through the dimmed reflection of a mirror. Finally, one day, Sir Lancelot rides by, his armour and horse trappings glittering in the bright sunlight like one burning flame, a meteor, trailing light. Overcome by the sight of his coal-black curls, the Lady escapes her tower and sets out in a boat towards Camelot, determined to find her knight. But the nameless curse cannot be evaded, and by the time her boat reaches the city she is no more than a beautiful corpse, which means that her virginity first signalled by the roses that guarded her bower has remained intact, despite her evident desire for Lancelot. The lesson is simple: it was the Ladys rejection of the boundaries that had been set for her that spelled her doom. Her action could not go unpunished. Dozens of paintings of the Lady of Shalott (and the inspiration for her, Elaine of Astolat) survive from the late nineteenth century; she represented a perfect tragic heroine for the Victorians. Shades of her story are also present in the fairy tales of princesses that have come down to us from the Brothers Grimm: Rapunzel, trapped in a tower; Snow White, prized for her purity; and Sleeping Beauty, preserved beautifully in sleep.