.st0{fill:#F1C81F;}.st1{fill:#414042;}

ARKTOS

London 2018

Copyright 2018 by Arktos Media Ltd.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means (whether electronic or mechanical), including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

ISBN

978-1-912079-11-7 (Print)

978-1-912079-10-0 (Ebook)

Translation

Jean Bernard

Editing

Martin Locker and Melissa Mszros

Design

Tor Westman

Arktos.com | Facebook | Twitter | Instagram

Dedicated to Franois-Xavier Dillmann.

Part I

F | U | Q | a | R | k | g | W |

f | u | a | r | k | g | w |

h | n | i | j | $ | p | y |

h | n | i | j | p | z(R) | s |

t | B | e | m | l | | d | o |

t | b | e | m | l | ng | d | o |

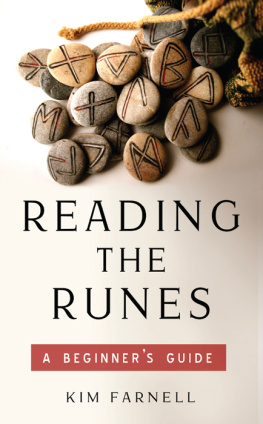

The older runic alphabet ( Fuark ),

comprising twenty-four letters grouped into three ttir.

The modern f uark , 16 letters.

Writing and Oral Tradition

A ny conception of culture that would designate the propensity to write as an indicator of a cultures wealth and complexity should be discarded, writes Eric A. Havelock. A culture can rely entirely on some kind of spoken communication and nevertheless be a culture with all that it entails.

That preliminary remark is useful in understanding why there is no common Indo-European term to refer to writing, in spite of the early development of several writing systems by ancient Near-Eastern cultures for administrative and utilitarian purposes. The Indo-European tradition is indeed essentially oral, and most Indo-European people seem to have voluntarily ignored writing, in its contemporary sense. Bernard Sergent describes that singular phenomenon as follows:

Writing is not categorically rejected , but it is put to the side to prioritize orality which comes first and foremost. In all ancient Indo-European cultures, or almost all of them, there is that rejection or marginalization, its use is very specific. It is that way because writing has an ambiguous status: on the one hand it has cons, written culture is perceived by those people to be of inferior quality compared to spoken culture [] but on the other hand it has pros, as writing is also perceived to be somewhat magical because it makes things last and popularizes them.

It is worth remembering that last point.

That is why writing plays no part in Vedic religion. The Brahmins role is to preserve the Vedas by reciting the text and learning it by heart to keep the oral transmission going. The sacred scriptures of the Indo-Aryan culture are a revelation confided to the ear, literally a hearing ( shruti ). While the Brahmin tradition exalts the strength of the spoken word (the very name of the Brahmins comes from brhman poetic spell), it neglects scriptural activities, but it does not mean that they are ignored. In the Veda language, there is no verbal root for the act of writing. In the Sanskrit vocabulary, the term for letter (verna) originally meant a kind of sound, it was a phonetics term. The earliest Sanskrit manuscripts only date from the 5 th century [Editors Note: All dates are AD unless specified], with their Asoka chancellery inscriptions. The Vedas, which have been transmitted orally for at least 4000 years, have only been written down in the 18 th century.

In Iran, the Avesta had also only been written down in the Sassanid period. The Celts shared the druidic teachings exclusively orally (this is why there are no remains of it). Arbois de Jubainville writes about druids from Gaul that we know that their teaching comprised making their students learn by heart a long didactic poem that they sang and that was actually memorized correctly by some students only after twenty years of studying. Cesar also emphasized the hostility which druids showed when they were told to write down their knowledge:

novice druids learned a lot of verses; many of them study for over twenty years; they dont think their religion allows the writing down of verses ( neque fas esse existimant eas litteris mandare ) but they do use Greek letters for all kinds of public and private uses.

Christian J. Guyonvarch, according to whom the conversion to Christianism implied a conversion to the written tradition, tells us that there are no native words in any Celtic language for the act of writing or reading. He adds that there is no ancient Celtic epigraphy for the regions far from the Mediterranean, as well as no writings in Gaulish in north-eastern Gaul. The Celtic name for writing (Old-Irish: scrib- ) comes from Latin scribo. In Scandinavia, the skalds art had also been transmitted orally for a long time.

Plutarch said about Numa that, according to him, it was wrong to preserve religious secrets in inanimate letters, which explains why he was thought to be the father of an unwritten tradition by Rome.

The importance of oral tradition must be kept in mind when one delves into writing.

Runic Writing

R unic writing is the writing system that was used to transcribe different Germanic languages before the Latin script, and then alongside it. It seems to have appeared roughly in the 1 st century AD and it was still used up to the 14 th century, when it began to fall out of use. However, it was still used marginally in the 17 th and 18 th centuries in some parts of the Swedish and Norwegian countryside (Dalarna, Hrjedalen, Telemark, Gotland, etc.) Its oldest variety comprises twenty-four signs or runes which form an alphabet which was given the name Fuark (Futhark) because of its particular order. Those twenty-four runes, materialized by vertical or oblique strokes, transcribe twenty-four sounds or phonemes. The Fuark comprises eighteen consonants and six vowels. Runes in the available body of inscriptions manifest a striking unity. Most of them are almost always the same; there are only minor variations and they rarely are isolated.

The former Fuark that had twenty-four signs stopped being used in the 8 th century. A new Fuark reduced to sixteen signs appeared in the beginning of the 9 th century in the Danish isles and in southern Sweden. Did it happen through a voluntary reform or was it rather a progressive evolution? Some specialists simply dont believe that the new Fuark comes from the old. Some others accept the derivation but they explain it through other means. Theres a disagreement between the upholders of the utilitarian hypothesis and those of the strictly linguistic theory. The former think that the reform comes strictly from a wish to simplify, which is quite dubious; the latter claim that it is the result of phonetic disruptions that affected the Proto-Scandinavian system. Lastly, some suggest (without any precise argument) a desire to make the Fuark more incomprehensible in the age of the first Christian missions. Ren L. M. Derolez writes that

Next page