Pagebreaks of the print version

AUTOPSY OF AN UNWINNABLE WAR:

VIETNAM

COLONEL (RET) WILLIAM C. HAPONSKI WITH COLONEL (RET) JERRY J. BURCHAM

All rights reserved, including without limitation the right to reproduce this ebook or any portion thereof in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of the publisher.

Copyright 2019 by William C. Haponski

ISBN: 978-1-5040-5912-1

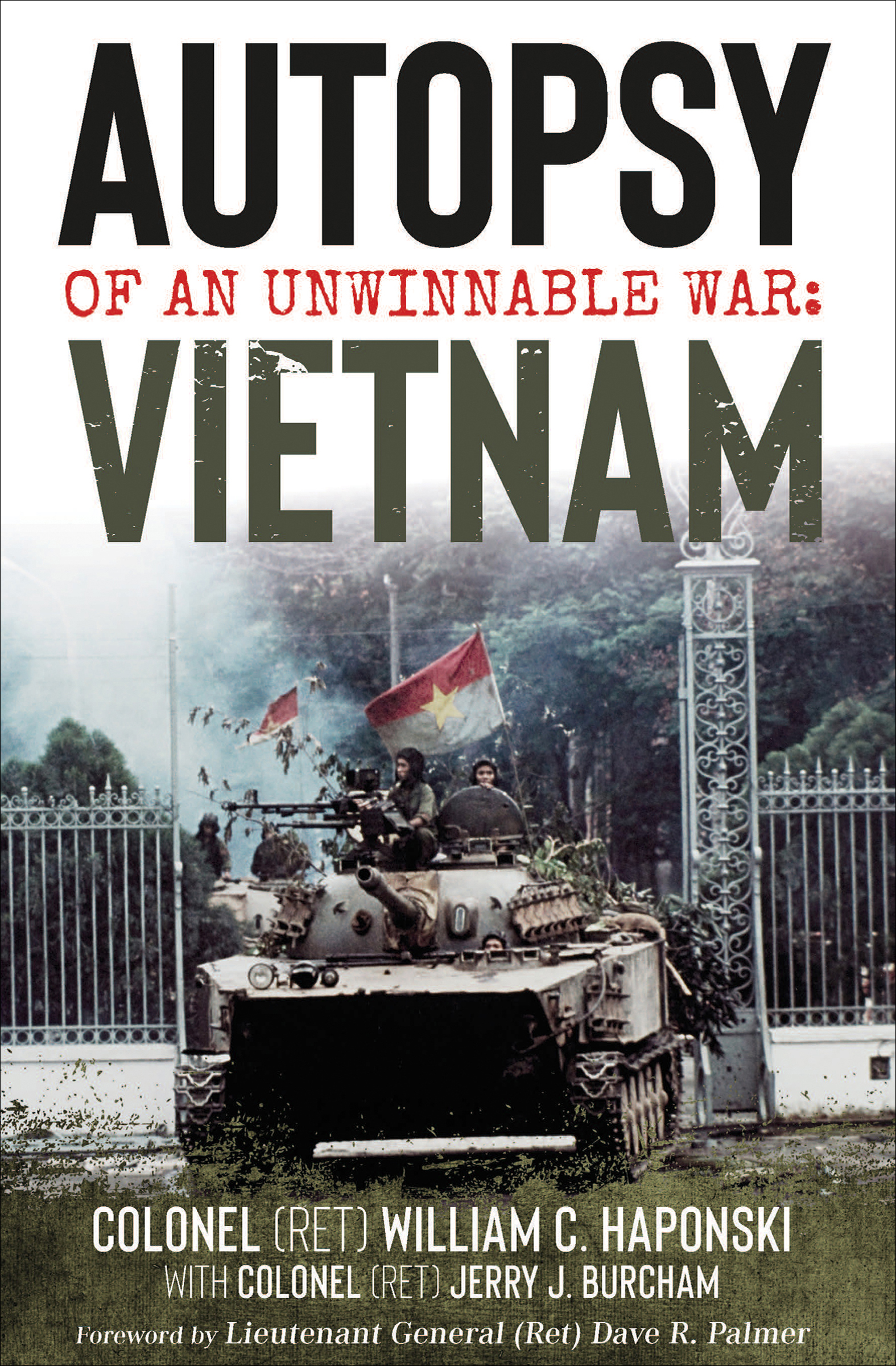

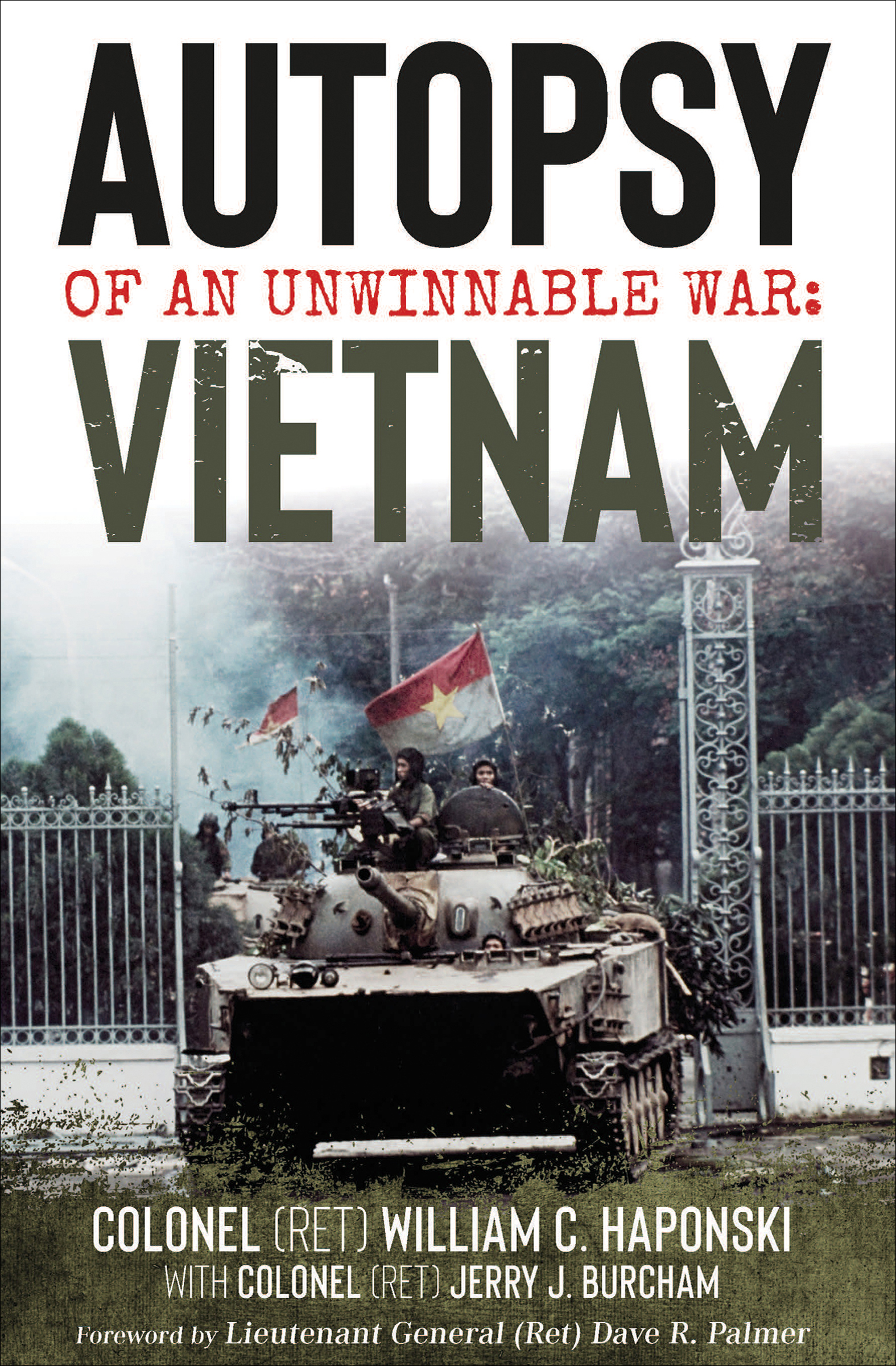

Front cover: A North Vietnamese tank entering the smashed-down gate of Independence Palace, April 30, 1975. (Roger-Viollet/TopFoto)

AN AUSA BOOK

Association of the United States Army

2425 Wilson Boulevard, Arlington, Virginia, 22201, USA

Casemate Publishing

1950 Lawrence Road,

Havertown, PA 19083, USA

www.casematepublishing.com

This edition distributed in 2019 by Open Road Integrated Media, Inc.

180 Maiden Lane

New York, NY 10038

www.openroadmedia.com

DEDICATED TO

General of the Army (Ret, French) Jean Delaunay

Genevive (de Galard) de Heaulme, The Angel of Dien Bien Phu

Colonel (Ret, French) Jean de Heaulme

Lieutenant Colonel Nguyen Minh Chau (Former Marine Corps, Republic of Vietnam)

Dr. Charles Lamb

Sandra Haponski

Maura and Stephen Cornell

Troopers of 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment, Vietnam and Cambodia

Troopers and Soldiers of Task Force 1/4 Cavalry, 1st Infantry Division, Vietnam

Troopers of 2/5 Cavalry (Airmobile), 1st Air Cavalry Division, Vietnam

You cannot kill an idea with bullets

General Jacques Philippe Leclerc

Commander, French Expeditionary Corps entering Vietnam 1945

Foreword

In the eight years from 1775 to 1783, American revolutionaries astounded observers in capitals all across Europe by defeatingagainst all oddsmighty Great Britain. They did so on the wings of a supremely motivating dream: to gain independence and to create a single nation united.

Nearly two centuries later, in the 30 years from 1945 to 1975, Vietnamese revolutionaries, driven by that very same dream, shocked the world by defeating, one after the other, three powerful foes: France, the United States, and their fellow countrymen in the southern half of Vietnam.

That is more than a coincidental similarity of aspirational ideas and surprising outcomes. Ho Chi Minh, the revered Communist and Nationalist leader of Vietnams revolutionaries from well before World War II, dramatically proclaimed his movements basis to a huge cheering throng in Hanoi in 1945. All men are created equal, he said. The Creator has given us certain inviolable Rights; the right to Life, the right to be Free, and the right to achieve Happiness. After pausing for effect, he continued, These immortal words are taken from the Declaration of Independence of the United States of America in 1776. In a larger sense, this means that: All the people on earth are born equal; All the people have the right to live, to be happy, to be free. He then invoked a second declaration, one guiding the later French Revolution, saying, Men are born and must remain free and have equal rights. Those are undeniable truths.

In the light of that animating visionthe unwavering idea of a united Vietnam free of foreign influenceWilliam Haponski holds that no French or American or South Vietnamese general could have gained a victory in Vietnam. That is his central theme as he tells the story of those three decades of war.

His telling is as unique as his thesis. Although the book itself is solid history Haponskis style is far from that of the traditional historian. While he writes often in the first person and does not shy away from placing himself in the story where appropriate, the tone is not that of a memoir. That out-of-the-ordinary approach reflects the author himself. Haponski has examined the war exhaustively for half a century, at every level from reflections on his first-hand experiences to post-doctoral research. The result is an absorbing blend ranging from the deeply personal to the academically professional. He has created a multi-dimensional narrative, at once alive and lucid.

A most valuable facet of the book is its focus on events inside Vietnam, placed in the clarifying framework of the four distinct phases of the long war. First, from 1945 to 1954, was the fight against the French. Next came a decade of transition, 1954 to 1964, as American military elements gradually took the place of French forces. Then, from 1965 to 1972, was the ill-fated American effort to defend South Vietnam. And finally, 1973 to 1975, the conquest of South Vietnam. To understand the Vietnam War, to really understand it, one must know the essence of all four phases.

Ever since North Vietnamese tanks rolled into Saigon in April 1975, journalists and generals and politicians and historians have debated heatedly over why America lost. Conclusions abound . It was a default, not a defeat. It was lost in Washington, not in Vietnam. Poor generalship is to blame. And on and on.

This book might not stop the debate, but it deftly rearranges the arguments. Haponski contends no generalno generalcould have mustered military forces to defeat the enduring idea of a free and unified Vietnam. That idea, so fervently held, provided the Vietnamese the will to persevere unto victory no matter how long it took or how painful the cost.

He asserts that in the end, willpower trumped firepower.

Lieutenant General (Ret) Dave R. Palmer

Preface

The politicians, media, and hippies lost that war for us! Since the April 30, 1975 fall of Saigon how many times have we heard it, or something like it? Especially from veterans who sacrificed so much, having buddies killed, getting wounded themselves, getting Dear John letters, acquiring cancers from toxins, trying to deal with their physical wounds and PTSD?

Many vets have expressed their feelings more colorfully: The ******* politicians , ******* media , and ******* hippies lost that ******* war for us!

Can the vets who fought close indown in the jungles and rice paddies, on the inland waterways, or overhead engaging the enemybe faulted for such a view when it also came as a post-war assessment from the very top? The senior American commander in charge of prosecuting the war during its buildup and peak of fighting was Admiral U.S.G. Sharp, Commander in Chief Pacific. As such, he was in overall charge of U.S. operations in the waron land, on water, and in the air. He concluded his memoir, saying: The real tragedy of Vietnam is that this war was not won by the other side, by Hanoi or Moscow or Peiping. It was lost in Washington, D. C.

This remains an all too common belief. The stark facts, though, are that the Vietnam War was lost before our first American shot was fired. In fact, it was lost before the first French Expeditionary Corps shot, almost two decades before us, and was finally lost when the South Vietnamese after us fought partly, then entirely on their own. It was not a war in which the generals of France, America, or South Vietnam could have led to victory.

It is important to understand why.

Americas inability to win in Vietnam cannot be just dumped conveniently onto the laps of the Washington politicians who established the rules of engagement within which the war could be fought. In essence those parameters were restrictions on crossing borders during the ground war in South Vietnam, blockading North Vietnamese ports, and conducting the air war over North Vietnam. Washington rejected the kick ass and take names approach of tough-talking men such as General Curtis LeMay and presidential candidate Senator Barry Goldwater. Their utterances on how to win the Vietnam Warbomb them back to the Stone Age; make that place a mud puddlewere roundly rejected by the American people and decision makers in Washington, and rightly so.