Campaign 4

Tet Offensive 1968

Turning point in Vietnam

James R Arnold

Series editor Lee Johnson Consultant editor David G Chandler

CONTENTS

BACKGROUND TO SURPRISE

The supreme command for the Viet Cong/North Vietnamese Army (VC/NVA) forces had a coherent strategy for conquering South Vietnam that the Americans neither fully appreciated nor effectively countered. In general terms, Communist strategists followed Mao Tse-tungs principles of guerrilla war. But ever inventive, the Vietnamese Communists adapted strategies for their unique circumstances. It was a strategy devised in the early 1960s when America only had advisers in Vietnam, and tenaciously clung to during the difficult years of massive US military activity until final victory. In essence it proved a war-winning strategy.

The overriding goal was to effect a withdrawal of American forces from South Vietnam to bring about negotiations leading to a new, Communist-dominated government in the south. To achieve this political end, the National Liberation Front fought on three fronts: political, military and diplomatic. The political battle involved mobilizing support from the people of South Vietnam while undermining the South Vietnamese government. The military component required confronting the Americans and their allies on the battlefield to inflict losses whenever possible. On the battlefield there were no objectives that had to be held. The diplomatic element of the three-prong strategy focused on mobilizing international opposition to the American war effort and promoting anti-war sentiment in the United States. As explained by a high-ranking Viet Cong:

Every military clash, every demonstration, every propaganda appeal was seen as part of an integrated whole; each had consequences far beyond its immediately apparent results. It was a framework that allowed us to view battles as psychological events.

In mid-1967, the Communist high command decided that the time was ripe for the crowning psychological event, a surprise nation-wide offensive to coincide with the Tet holidays.

About the time when Communist planning for the Tet Offensive began, top-level American civilian and military planners met in Honolulu. The conference focused on how to interdict the flow of enemy troops and material into South Vietnam. Inevitably, this led to consideration of higher strategy. The conferences final report stated: A clear concise statement of US strategy in Vietnam could not be established... A war of attrition provides neither economy of force nor any foreseeable end to the war. The conference could simply not identify anything worthy of being called a strategy.

In the broadest terms, the American high command had pursued a two-part scheme since 1966. General William C. Westmoreland described this approach in an interview as the Tet Offensive was winding down:... the [South] Vietnamese forces would concentrate on providing security to the populated areas, while the US forces would provide a shield behind which pacification could be carried out. The idea was that the American forces would operate away from populated areas where they could use their superior firepower and mobility to counter the North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong mainforce units. Speaking after the war, Marine Corps historian and Vietnam veteran Brigadier General Edwin Simmons commented:

Its true we violated many of the basic principles of war. We had no clear objective. We had no unity of command. We never had the initiative. The most common phrase was reaction force we were reacting to them. Our forces were divided and diffused. Since we didnt have a clear objective, we had to measure our performance by statistics.

Thus the sterile tabulation of Battalion Days in the Field, hamlets controlled, or most notably body count replaced clear strategic direction.

According to Westmorelands strategy, US forces were to engage regular enemy formations while ARVN forces concentrated on pacification. The problem was finding the enemy. Men of the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) the lite First Team conduct combat assault into the An Lao Valley.

During the months leading up to the Tet Offensive, President Lyndon Johnson and his administration told the American public that the Allies were winning the war. This left the public unbraced for the coming shock. A well-intentioned man, Johnson lacked the vision to guide the country to a satisfactory resolution of the war. Here he shakes hands during a visit to a hospital at Cam Ranh Bay in 1967.

President Lyndon Johnson tried to counter the growing public doubts about the war by a carefully crafted propaganda campaign in late 1967. It claimed that the Communists were slowly losing the war. He sought to gain support for a longterm, limited-war policy. With hindsight it is clear that this approach contained neither a decisive war-winning stategy nor a plausible diplomatic outcome. Worse, from the administrations standpoint, the implicit message was that there would be no unexpected battlefield surprises.

The Plan is Born

In July 1967, the Communist high command, including political and military leaders from both North and South Vietnam, met in Hanoi. Because North Vietnam recalled its foreign ambassadors to attend the meeting, American intelligence learned of the unusual gathering. It could have been the first piece in the intelligence puzzle leading to anticipation of the coming offensive. Instead, analysts believed the meetings purpose was to consider a peace bid.

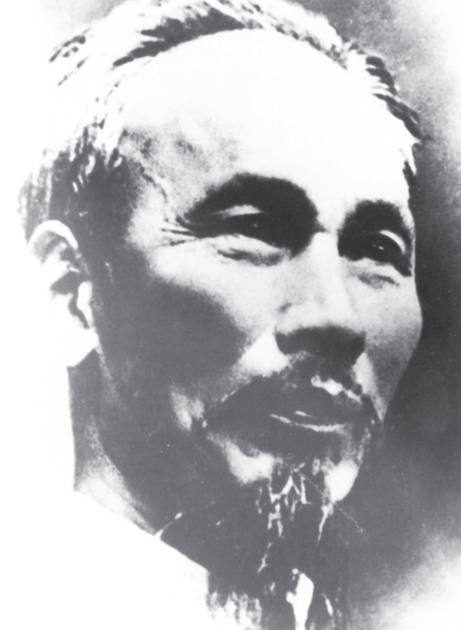

In the summer of 1967 North Vietnamese warriors and diplomats met in Hanoi and decided to take an immense strategic gamble. While the Tet Offensive was Defence Minister Giaps brainchild, Ho Chi Minh gave his blessings to the effort. His recorded tapes were meant to be played on captured South Vietnamese radio stations. Communist planners believed that everyone would rally to the popular Uncle Ho and help drive out the hated foreigners.

The offensive required a long lead time because of the difficulty of moving supplies south along the tortuous Ho Chi Minh Trail. This section of the supply line consists of a road carved into the side of a hill for the movement of light trucks.

Reviewing events, the Communist leaders recognized that heretofore their battlefield strategy had relied upon well-planned, periodic small- to medium-sized surgical strikes against selected targets and daily small-scale actions designed to raise the enemys anxiety level and destroy his self-confidence. However, aggressive American tactics during 1967 seemed to auger poorly for the future. A Viet Cong general explains: