The Vietnam War was one of the key events of the Cold War (1947-1991), as well as the longest and most destructive conflict in the history of US-Vietnamese relations.

After the First Indochina War against the French colonisers between 1946 and 1954, Vietnam was split into two territories, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in the north and the Republic of Vietnam in the south. This division led to a military and political conflict which devastated the Vietnamese population during the 20 years of war that followed. When US forces entered the conflict in 1964, the discord between these two ideologically opposed populations only intensified, resulting in profound national trauma. Constant battles and bombing campaigns left the country drained and powerless to manage the vast quantities of toxic waste which continue to pose health risks to its inhabitants even today.

The Vietnam War had unprecedented consequences not only on American policy, but also on the American population, who witnessed the horrors of an all-out war against enemies who were sometimes impossible to detect or even figments of the US imagination. The conflict is etched into the memory of American veterans as a human disaster, and the damage inflicted on the Vietnamese population has yet to heal.

Political and social context

French colonialism in Indochina

Vietnam was a French colony from 1883 to 1954. It was made up of three states, Tonkin, Cochinchina and Annam, and from 1887 onwards was part of the Indochinese Union, which also comprised Laos and Cambodia. The country was partly run by the French colonisers, who developed an increasing number of tea, coffee, rice, pepper and rubber plantations and mined coal, zinc and tin for the profit of mainland France. The countrys indigenous inhabitants did not have the same rights as its European minority: even though the Code de lindignat (Code of the Indigenate) and the system of forced acculturation were not applied, unlike in Frances African colonies, the native Vietnamese formed a diverse proletariat who worked in the countrys rice fields, factories and mines.

The Code de lindignat

The Code de lindignat was a piece of legislation introduced in French colonies in 1887. It divided the population into two categories: French citizens from France and French subjects (Africans, Algerians, Malagasy, Antilleans, and so on), who were deprived of most of their freedoms and political rights. Their civil rights were limited to the right to follow their religion and traditional customs. The codes discriminatory measures included forced labour, the requisitioning of indigenous inhabitants property and head taxes on the reservations, among others.

Acculturation in the colonies was based on assimilation or coexistence: indigenous inhabitants were forced to learn about the colonisers culture through secular and religious schools, and their traditions were denigrated in favour of Western customs. The colonial administration rejected traditional thinking and ways of life, and imposed a system and lifestyle modelled on those of Europe.

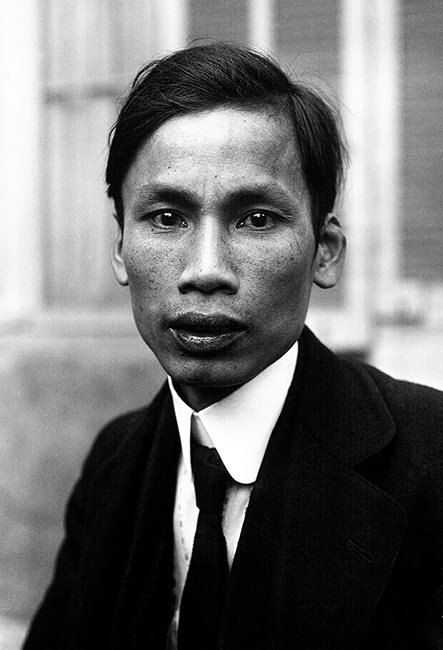

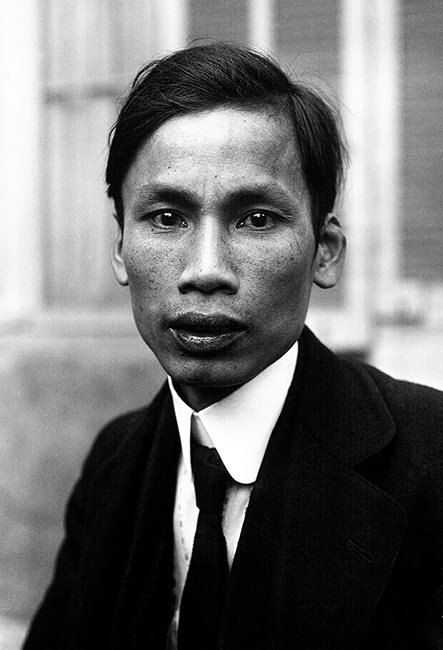

The native Vietnamese faced difficult working conditions, and corporal punishment and pay deductions were common occurrences. The mistreatment of workers created a breeding ground for nationalist and Communist movements such as the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV), which was founded in 1930 by Nguyn Sinh Cung (1890-1969), who later assumed the name Ho Chi Minh.

Ho Chi Minh in 1921.

The CPV was initially part of the French Communist Party, but in May 1931 joined the Communist International and adopted the name Indochinese Communist Party (ICP). The ICP was responsible for the first calls for independence, which became more vociferous in 1941 when Ho Chi Minh founded the Viet Minh, which brought together the ICP and several nationalist groups. The Viet Minh paved the way for anti-French and then anti-Japanese resistance, as Indochina was occupied by Japanese forces between March and September 1945.

The movement became particularly active from early 1945 onwards thanks to material support from the USA, which had decided to drive the French out of Indochina following the Yalta Conference (4-11 February 1945) and the Potsdam Conference (17 July-2 August 1945). However, after the fall of the Vichy regime and the liberation of France, the countrys new provisional government, led by General Charles de Gaulle (1890-1970), directed new efforts at its colony in Indochina, and British and Japanese troops left the territory.

However, the Viet Minh and other independence movements were trying to gain control of Vietnam, and Ho Chi Minh called for a general insurrection on 13 and 19 August 1945. His party subsequently took control of all Hanois public services, and by 20 August, Tonkin (North Vietnam) was entirely controlled by revolutionary committees.

In response to attacks on French citizens, France sent armed troops to the region. Negotiations with the Viet Minh led to the signature of the Ho-Sainteny agreement on 6 March 1946, in which France recognised Vietnam as a free, but not independent, state. However, France proved unwilling to respect its colonys new status, and decided to reopen hostilities and take control of the territory by force. This resulted in open war between France and Vietnam.

The First Indochina War (1946-1954)

After Japanese troops withdrew from Indochina, France wanted to regain control of its Asian colonies, particularly Vietnam. At that time, the country was controlled by the Viet Minh, who wanted to turn it into an independent Communist republic.

The war began on 23 November 1946 with the bombing of the major industrial city of Haiphong, which was taken back from the Communists after a series of destructive raids. The Viet Minh retaliated by executing French soldiers in Hanoi on 19 December. As a result, the simmering tensions between Ho Chi Minhs Viet Minh and the French colonial troops, who wanted to preserve mainland Frances grip on Vietnam, developed into a full-blown war that would last for eight years.