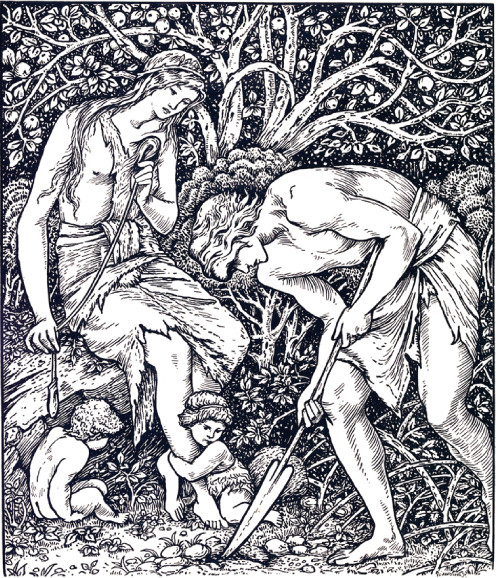

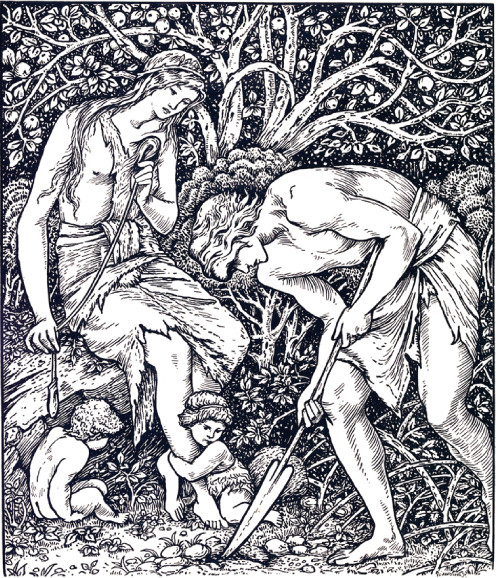

When Adam delved, and Eve span,

Who was then a gentleman?

A 14th century rhyme

According to Genesis, in the beginning there were only workers; Adam who delved and Eve who span.

About the author

Mark OBrien is a socialist based in Liverpool, UK. He researches and publishes on working class social history and aspects of social inequality in British society. His previous publications include Perish the Privileged Orders: A Socialist History of the Chartist Movement.

WHEN ADAM DELVED

AND EVE SPAN

A History of

the Peasants Revolt of 1381

Mark OBrien

For Rohina and Ruben

When Adam Delved and Eve Span

A History of the Peasants Revolt of 1381

By Mark OBrien

Published 2016 by Bookmarks Publications

c/o 1 Bloomsbury Street, London WC1B 3QE

Bookmarks Publications

Cover image: Richard ii meeting the rebels (detail)

from Froissarts Chronicles

Designed and typeset by Peter Robinson

Printed by Melita Press

ISBN 978-1-910885-26-0 PBK

978-1-910885-27-7 Kindle

978-1-910885-28-4 ePub

978-1-910885-29-1 PDF

Contents

Preface to the second edition

IT IS difficult to talk of a historical episode that occurred more than six centuries ago without giving way to a sense of distance. The strangeness of the images from manuscripts and woodblock illustrations, the unfamiliar trades, the pervasive presence of the Church, the brutality of life and so on combine to create the medieval world in our minds as something utterly alien to our own.

Of course, in an everyday sense this is true. It is difficult for us (impossible really) to imagine ourselves into the experience of the late medieval peasant, or to properly understand how they bore the burden of the unremitting toil that was their lot.

However, looked at differently, there is a sense in which their experience is more familiar than we might at first have thought. It is in the political sense of the issues they faced and the injustices inflicted upon them that they come closer to us. The ruling class of that erathe royal court and its supporting infrastructure of manorial estates, abbeys, magistrates, prisons and constables conspired to drive the peasantry back to an earlier, pre-plague and more immiserated condition. They expected them to pay for the successive English wars of adventure in France. They strengthened the legal power of the manor to keep their labourers from wandering, tearing up the few rights of redress that existed. Socially, they treated the peasantry with contempt.

The political parallels we can see with this historical era and our time have intensified since this book was first published. Our own time is one in which the already poor and put-upon are being pushed further down the social pyramid into ever more desperate straits, in which previously taken-for-granted liberties are being removed, and in which the costs of war are being carried by the poorest in society as state resources are diverted from meeting social need to covering military budgets.

The peasants of 1381 should be appreciated for one further thing, however; they refused what was expected of them. The anger they felt, we can understand; their chafing at the social restrictions placed upon them, we can identify with; and the rising they undertook, we can be inspired by. The story of the Peasants Revolt of 1381 is a wonderful historical drama; however, it is also an allegory for our times.

Mark OBrien

Liverpool, 2016

Preface to the first edition

THE AIM of this book is a modest one. It is to tell the story of one of the most extraordinary episodes in English history in a manner that is, hopefully, accessible, exciting and enjoyable to the reader. It does not offer new research drawn from recently discovered primary sources or the like. Nor does it offer original analytical frameworks or perspectives. Indeed, the reliance on the work of others will be obvious and acknowledged throughout.

It is also beyond the scope of this bookas well as the competence of the authorto assess the accounts given in the early chronicles. As is well known among scholars of the period, the chronicles do not agree on some important detailsthe role of John Ball, the precise sequence of events on 13 June 1381, the location of the king at various points and so on. However, the general consensus given in the most authoritative histories has been taken at face value and presented in this historical introduction.

What is offered here is an account that is overwhelmingly sympathetic to the key actors in this unique historical drama the peasants of late-14th century England. For what it is worth, it is also an account told by someone who, on discovering the story for himself, was amazed and inspired. It is this sense of inspiration and the desire to share the story with a wider audience that has motivated the writing of this short book.

Mark OBrien

Liverpool, 2004

1

The medieval scene

NOT SELDOM I please myself with trying to realise the face of medieval England; the many chases and great woods, the great stretches of common village and common pasture quite unenclosed; the rough husbandry of the tilled parts, the unimproved breeds of cattle, sheep and swine, especially the latter, so lank and long and lathy, looking so strange to us; the strings of packhorses along the bridle roads; the scantiness of the wheel roads, scarce any except those left by the Romans, and those made from monastery to monastery; the scarcity of bridges, and people using ferries instead, or fords where they could; the little towns well be churched, often walled; the villages just where they are now (except for those that have nothing left but the church to tell of them), but better and more populous; their churches, some big and handsome, some small and curious, but all crowded with alters and furniture, and gay with pictures and ornament; the many religious houses with their glorious architecture; the beautiful manor houses, some of them castles once, and survivals from an earlier period; some new and elegant; some out of all proportion small for the importance of their lords.

In this passage William Morris knowingly idealises the medieval world by way of contrast with the horrors and ugliness of the industrial towns of his own day. The scenic vista of feudal times in the eye of Morriss imagination of course disguises the grim realities of life for most people of the time. This passage, however, evokes something of the way things must have looked. With most of the country covered by wood and fen this was indeed a more natural, a more nature-dominated, world than our own. The air the people breathed was clean and the water they drank was uncontaminated by chemical and human waste. But equally the diseases they contracted were debilitating, regular and frequently fatal. This was an age of fears. Fears of the wildness of the woodlands, of the vagaries of climate, of the failure of harvest and of the dangers of childbirth. When times were good, when the harvest was successful, there could also be drunkenness, celebration and merriment within closed and strong village communities.

In our period, the mid to late 14th century, 95 percent of the population was rural. People lived in small, scattered village communities that were located far from other settlements and almost autonomous of their neighbours. They worked the

Next page