For distributor details and how to order please visit the Ordering section on our website.

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publishers.

The rights of Gavin James Bower as author have been asserted in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

We operate a distinctive and ethical publishing philosophy in all areas of our business, from our global network of authors to production and worldwide distribution.

Foreword

My names Gavin, and Im a Cahunian.

My addiction to The Artist Formerly, and indeed Formally, Known As Lucy Rene Mathilde Schwob dates back to 2004. I was asked to write a feature for FLUX magazine, on an exhibition taking place at the Manchester Art Gallery. The exhibit included a smattering of striking self-portraits taken by a lesbian surrealist turned resistance fighter with a penchant for Marxism and an androgynous pseudonym: Claude Cahun.

I did what any young journalist would and hopelessly over-researched the eight-hundred-word piece, reading everything I could get my hands on through the University of Manchester library. I was hooked. Here was an artist not in the traditional sense perhaps, but in any case an individual whose life was her art and for whom the epithet artist could be reasonably applied who was practically unknown beyond the auspices of a handful of art historians, students and the narrowest of readerships; and yet Claude Cahun is, to my mind then and still years later, the most singularly fascinating creative spirit of the twentieth century. A writer of poetry and prose, self-centered curator of tableaux, a skilled sketch artist, photographer and muse, a poseur, actress and performer, composer of objets dart, a propagandist and a saboteur Claude Cahun was nevertheless all but forgotten by the time of her death, now nearly sixty years ago, and has only in the last two decades enjoyed something of a renaissance.

Ive spent the past year attempting to discover not only how Claude Cahun vanished from history, but also the reason for her disappearing act. Its my contention that to be a Cahunian is to wish that status on everyone; to not stop until her name resonates with more than just a handful of loosely connected enthusiasts. But thats not enough, for to do so demands a certain focus a degree of understanding as well as context that transcends my arrogant notion that you, the reader, should know about Claude Cahun. I need to explain why you should know about her, not merely what.

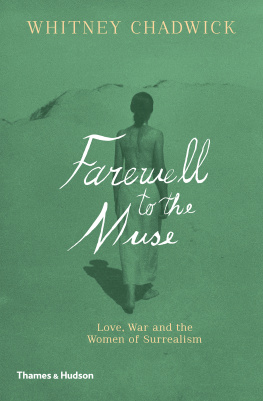

As a writer my instinct, on beginning this search, was to concentrate on Cahuns literary output and strip away the art historical narrative that has built up around her photography for its with the latter that art historians have, if they are aware of Cahun at all, become preoccupied. What of her writings place among the various tracts of Surrealism, or its merit in relation to her other influences? What of its context in the male-dominated canon of avant-garde literature? And what of the obvious comparisons to be made with other female writers working in Paris at the time particularly those who comprised one half of a kind of lesbian literary power-couple, most notably Gertrude Stein (with Alice B. Toklas) and Adrienne Monnier (with Sylvia Beach)? These questions warrant an answer, but it should be provided elsewhere, in a work of literary theory, which this is not; further, to ask them in isolation is to render any study at all of Cahun futile. How can one separate out the works of an artist, effectively decide to pick and choose, while attempting to write something sensible about their art?

Indeed, a disproportionate amount of time has already been spent on only part of Cahuns oeuvre not to mention her after-the-fact influence on the gender-politico debates of the seventies; the artist, stranded in historical No Mans Land, wasnt even known to her acolytes at the time. More still has been made of her time-continuum-defying one-upmanship when it comes to visual artists who would inadvertently mimic her, none more so than Cindy Sherman. The auto-portraits of each are eerily similar noteworthy, if only for their mutual exclusivity: Sherman was of course unaware of Cahun and, naturally, vice versa. A remarkable coincidence, but given this focus on Cahuns photography putting aside the inconvenient truth that, as a cult artist, she has only enjoyed brief revivals of interest over the last two decades scant attention has been paid to her writing. Whats more, all this is despite the fact that her photography was not in the vast majority of cases intended for public scrutiny. Putting aside the images composed by Cahun for use in her literary works, along with one lithograph and illustrations for a 1937 childrens book (Le Coeur du Pic, by Lise Deharme), Frontire humaine (Bifur 5, 1930) was the only self-portrait published in Cahuns lifetime.

Still, to ignore Cahuns visual output in order to pigeonhole her as just a writer would tell only half the story perhaps more, but in any case not all. In appreciating what makes Cahun worthy of anyones time after all these years we cannot have one without the other. Further, to pay no attention to her photography whatsoever would be downright idiotic; some of her work is astonishing and all of it deserving of an audience. After all, by experimentation with costume, make-up and pose, by manipulating the existing categories of identity and defying the boundaries of established femininity, by fusing the traditional subject-to-object dichotomy, and by placing herself firmly at the centre of her work, Cahun challenged the surrealist conception of woman in ways never before seen. Though this has been amiably argued elsewhere and here is not the place to expend yet more energy illustrating the fact she is certainly worthy of greater fanfare solely as a visual artist.

Through every medium she employed, Cahun was willfully narcissistic in her quest for self-identity. As the centre of her own work, she refused to submit either to narratives or preconceived relationships of subject to object, while she returned the scrutiny of her audience and, indeed, her own investigations with uncompromising effrontery. She sought to reflect rather than deflect, and never shied away from what was for her an unanswerable question: Who am I? Rather than attempting to solve the mystery of Claude Cahun by positing her, explaining her, and thereby somehow understanding her we would be advised to ditch our agendas, strip away the art historical narrative, and follow her lead.

Cahun was far from prolific. Of the work that survived her tumultuous lifetime and the passing of years since her death, the question of authorship not to mention target audience is by no means in all cases clear. She was the most unreliable of narrators, disingenuous, dissembling and deliberate in subsuming her identity while, on the surface at least, attempting to reveal it. And yet, none of this matters because to be a Cahunian is akin to addiction: to art for arts sake; to the most unknowable of all things; to a life lived without compromise, with courage and conviction. When Marcel Duchamp said my art is that of living, he was talking about individuals like Cahun for her life was a remarkable one, and a masterpiece unparalleled by anything she would ever produce on paper or through the lens of a camera. To us Cahunians, Claude Cahun