Contents

Guide

Page List

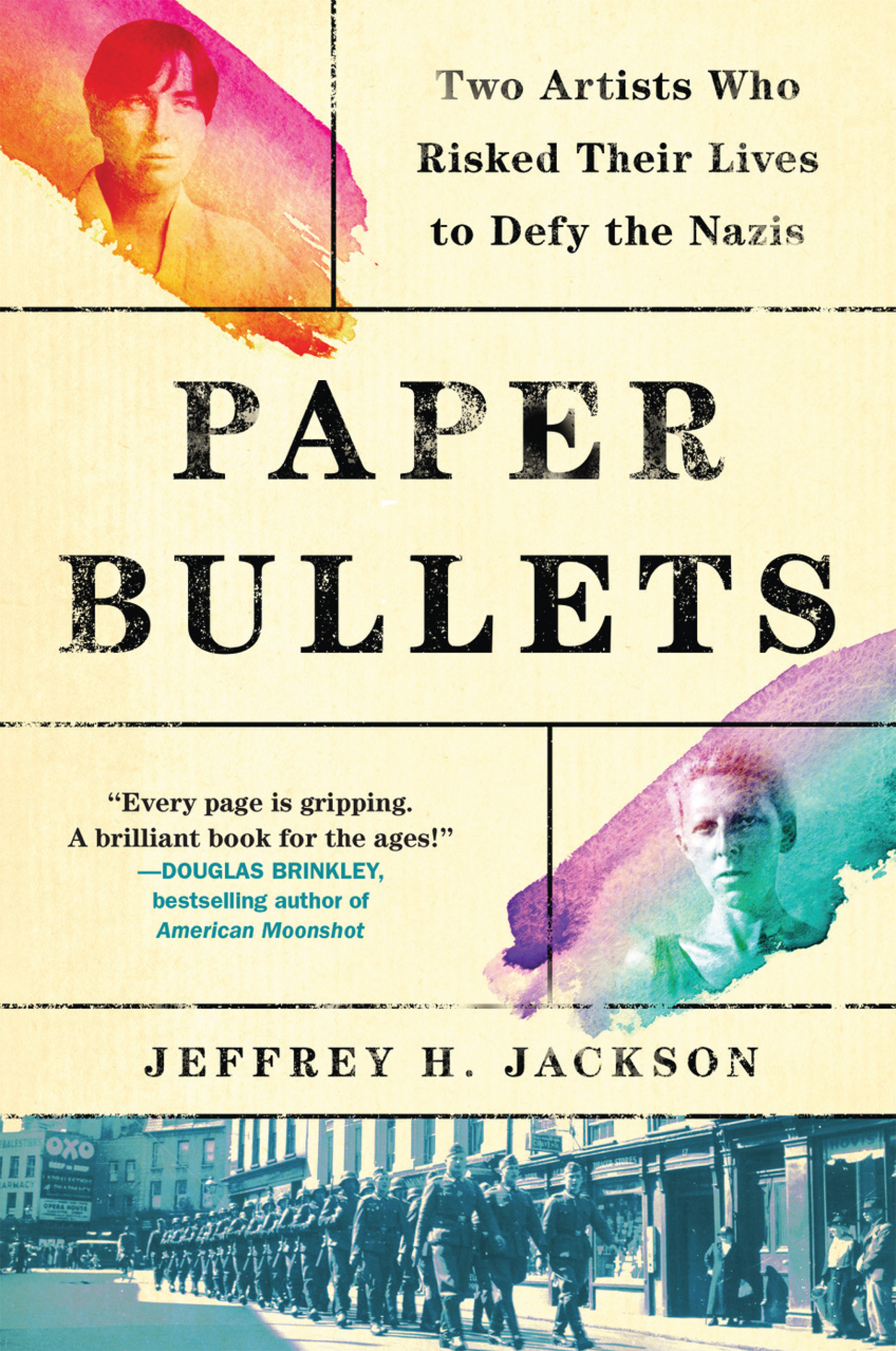

Paper Bullets

Two Artists Who Risked Their Lives to Defy the Nazis

Jeffrey H. Jackson

Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill

Published by

Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill

Post Office Box 2225

Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27515-2225

a division of

Workman Publishing

225 Varick Street

New York, New York 10014

2020 by Jeffrey H. Jackson. All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020018040

eISBN: 978-1-64375-112-2

For Ellen

Contents

Prologue

They Have Not Caught You This Time

On The Morning Of July 25, 1944, Lucy Schwob and Suzanne Malherbe went into St. Helier to do some shopping. The trip was part of their regular routine. Outside the offices of the Jersey Evening Post, they glanced up at the large clock at the top of the building. Suzanne leaned in and whispered to Lucy to keep watch. Then Suzanne scanned the long row of police cars the Nazi occupation forces always parked along Charles Streeta reminder of how heavily the Germans censored the islands only newspaper.

Suzanne took a small piece of paper out of her pocket and began moving carefully toward one of the police cars as Lucy stood by on lookout duty. Suzanne stuck the gummed paper on the windshield. The cowardly bureaucrats of the police, who live on lies and shameful cruelty, will be destroyed by the Soldiers with No Names, the note read.

No one seemed to be paying any attention to the middle-aged women in Burberry trench coats with bright scarves tied around their heads. Suzanne quickly attached papers to a few more windshields and casually strolled away, her Wellington boots thumping on the pavement. If anyone asked the women what they were doing, their shopping bag would provide a ready alibi.

After finishing their secret mission, along with some mundane errands, they met up with their housekeeper, Edna Le Neveu, and boarded one of the wood-burning buses to head back home on the other side of the island. Lucy held a package of cigarette papers they had just bought at the newsstand. These papers were destined to become a new batch of notes for the Nazis. In her pocket, alongside more of their notes, Suzanne could feel the bright blue Milk of Magnesia bottle. It did not contain the digestive medicine, however, but instead an overdose of the powerful barbiturate Gardenal, in case the Germans caught them in the act.

Jersey native Edward Le Quesne was also on board as the bus bumped along its route overlooking St. Aubins Bay. Le Quesne had worked as a plumber for many years and served in the leadership of his union. He was elected as a deputy in the States, the islands governing body, where he rose to president of the Labour Committee and became a member of the Superior Council during the war. An avowed pacifist, Le Quesne remained one of the most popular politicians during the occupation because he was occasionally willing to run afoul of occupation regulations. Earlier in the war, he had been arrested by the Germans for possessing an illegal radio.

With no warning, the bus came to an abrupt halt, and a fair-haired soldier climbed aboard. Everyone off the bus!

Le Quesne, grandfatherly at sixty-two years old, with round glasses and a receding hairline, fumbled off the vehicle. Random inspections like these were an experience we have to tolerate under Nazi rule, he noted with resignation in the diary that he kept on paper made from the covers of tomato packing crates. Most people were used to this treatment. Le Quesne had done nothing wrong, so he was more annoyed than fearful. Lucy clutched her parcel a bit tighter.

Outside, the soldier approached each commuter. Suzanne noticed his bright blue eyes. Le Quesne remembered the litany of commands and questions: Please show me your papers. How old are you? What is your occupation? Where were you born? Where do you live? How many children do you have? With his critical eye, the German carefully looked over each passengers documents until satisfied, saying very little other than what was necessary to get his answers. If something was suspicious, or if passengers had forgotten their documents, Le Quesne observed, they were told: Someone will visit you in your home.

Then the soldier approached Lucy and Suzanne. Lucy recalled the scene several years later in a scrapbook of notes that might have formed the basis of a memoir if she had lived long enough. She titled these reminiscences The Mute in the Middle of the Muddle. Show me your registration card, the German demanded. He stood in front of Lucy, glaring at her. A look of recognition crossed his face when he saw a familiar name. Schwob. What kind of name is that? The document listed French as her national origin. She explained nervously that she was an orphan and raised by a Frenchman. Perhaps you are Alsatian? Maybe, she replied, but admitted that she didnt really know. Lucy stated that she had been on Jersey for some thirty years.

Nearly everything she had just told the German about herself was a calculated lie. She invented a new backstory for herself, and not for the first time.

Her fabricationperhaps planned, perhaps on the spotwas important because Lucy had a lot to hide. It obscured the fact that she and Suzanne had both grown up as the daughters of wealthy and prominent residents of the western French city of Nantes. Lucys mothers family was Catholic, but her fathers family was Jewish. The Schwobs had enjoyed coming to Jersey during regular vacations in Lucys youth, and she and Suzanne had visited together in the early 1920s. But Lucy had certainly not lived on the island for three decades.

Her invention also left out the womens nearly twenty years of living in Paris as part of the cutting-edge art world, she as a writer and Suzanne as an illustrator. The two collaborated on experimental photography and photomontage, and their sometimes-alarming images challenged conventional notions of beauty and art, and expectations about how women were supposed to look. They worked alongside surrealists to push artistic boundaries and create what the Nazis would come to denounce as the degenerate art that supposedly undermined Western civilization. In those years, Lucy and Suzanne also befriended communists, immersing themselves in intense political debates about the fate of Europe.

By the 1930s, Paris had become a city roiling in the turmoil of the Great Depression and radical politics as right-wing groups chanted anti-Semitic slogans and fought with left-wingers in the streets. Artists took sides too, squaring off in the pages of journals and around the tables in cafes.

But the battles became too much, and Lucys years-long struggle with illnesspoor eyesight, a chronic kidney disease, intestinal problems, and recurring migrainesstressed her nerves to the breaking point. She had grown dependent on Gardenal to help manage her insomnia, although she frequently read or wrote her way through long nights and into early morning hours. Suzanne took good care of Lucy, but life in the French capital was overwhelming, and they decided to return to the island to find quiet.