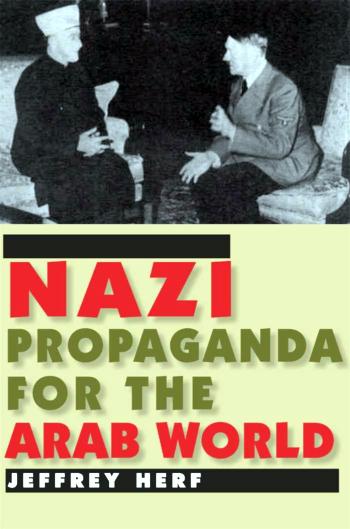

Nazi Propaganda for the Arab World

Nazi

Propaganda

for the

Arab World

JEFFREY HERF

For Sonya and In memory of Jeannie Rutenburg, 1950-2009

Contents

ix

xi

xv

Preface

During World War II, the Nazi regime distributed, in Arabic, millions of printed leaflets and broadcast thousands of hours of shortwave radio programs to diffuse its ideology throughout North Africa and the Middle East. This book is a history of the ideas, individuals, and institutions involved in that effort. It draws on underutilized and unused archival sources to shed new light on the nature and scope of Nazism's ideological extension beyond Europe and the adaptation of its messages to the local politics and Islamic religious idioms of the region. It is a sequel to my previous work on Nazi propaganda aimed at a domestic audience. It adds to a historical scholarship that draws attention to the connections between World War II and the Holocaust in Europe and the Mediterranean and Middle Eastern dimensions of the war, and in particular to the failed attempt to extend the Holocaust to encompass the Jews in the countries of that region. As Alexander Kirk, the American ambassador to Egypt, put it in one of his many important wartime dispatches from Cairo about `Axis Broadcasts in Arabic;' Nazi shortwave radio poured forth hatred of the Jews "ad nauseam." The fate of 700,000 Jews living in the Middle East and North Africa depended on the outcome of the fighting between the Allies and Axis forces in North Africa. The propaganda barrage was an instrument used simultaneously to try to win the war against the Allies as well as to extend Nazism's genocide of the Jews. The diffusion of anti-Semitism was at the center of this effort.

Although this book is first and foremost a work of history about a distinct set of events in the past, it also documents a chapter in the history of the lineages and origins of ideas that emerged in Arab radicalism and Islamist politics after World War II. Radical anti-Semitism and the ideas of Nazism and fascism ceased to play a major role in European politics after 1945, but traces of the melange of Nazi ideology, radical Arab nationalism, and fundamentalist Islam that emerged in wartime Berlin did persist in the Middle East. Though they were often on the political margins, these ideologies were not discredited as extensively as they were in Europe. The political and ideological collaboration between officials of the Nazi regime and pro-Nazi Arab exiles in wartime Berlin introduced the ideas of twentieth-century European totalitarianism into an Arab and Islamic context. They did so both by secular denunciations of Zionism, Britain, the United States, and the Soviet Union and by asserting that there was an elective affinity between Nazism and what the Nazis claimed Islam to be. In this sense, the propaganda campaign was a chapter in the history of what I earlier called "reactionary modernism;' namely, the use of the most modern technology of the time to advance a political and cultural revolt against the West's liberal political traditions.

In postwar Europe, on the whole, anti-Semitic conspiracy theories and equally absurd hatreds rooted in ancient religious texts became a disgraced and dead relic buried in the ruins of the Third Reich. But in the postwar Middle East, these notions persisted in elements of radical nationalist and Islamist politics. The ideas and events examined in this book are one piece of the explanatory puzzle that accounts for this tragic afterlife in another context. An adequate history of the reception of this propaganda offensive awaits the efforts of scholars who work primarily on North Africa and the Middle East. Here I offer readers the most extensive record to date of what Nazi Germany was communicating to Arabs and the Muslims of North Africa and the Middle East during World War II.

As a work of intellectual and cultural history, this book also documents and interprets an important chapter in what one could call the dark history of globalization and cultural interaction. A simple-minded optimism seeks to convince us that contact and communication between people from different cultures will invariably foster international understanding, peace, and goodwill. Sometimes it has. In this case, the collaboration of officials of the Nazi regime with Arab allies in wartime Berlin demonstrated that the opposite was also possible. The more these political allies exchanged ideas, the more they reinforced, renewed, and accentuated some of the worst elements of their respective civilizations, namely, hatred of Jews and of Western political modernity. This direct gaze at the results of their collaboration during World War II will, I hope, contribute to the contemporary criticism that the aftereffects so richly deserve.

Acknowledgments

With pleasure, I acknowledge the people and institutions that supported the research and writing of this book. Thanks are due to archivists at the United States National Archives and Records Administration in College Park, Maryland, for their assistance in locating relevant files of the United States Department of State. Lawrence MacDonald, in particular, helped unravel some of the complexities of the World War II-era American intelligence files. My fellow historian Richard Breitman, himself a pioneer in the scholarly use of American intelligence and diplomatic files in the United States National Archives regarding the Holocaust, shared both his deep knowledge of them as well as encouragement for this project. His assertion that our National Archives contain a great deal of material of interest to historians of modern European history has turned out to be even more accurate than I anticipated.

A fellowship at the American Academy in Berlin in fall 2007 and the support of its director Gary Smith and his excellent staff facilitated research in German archives. Yolanda Korb's assistance with library acquisitions was particularly helpful for the research. Archivists Martin Hanselmann, Mareike Fos- senberg, and Dr. Martin Kroger at the Political Archive of the German Foreign Ministry (PAAA) in Berlin; Elfriede Frischmuth at the German Federal Military Archive in Freiburg (BA-MA); and staff at the German Federal Archive (BAB) and at the Zentrum fur Moderner Orient (ZMO), both in Berlin, facilitated my work in their collections. A sabbatical leave from the University of Maryland, College Park, for spring semester 2008 gave me the time needed to complete the research and much of the writing.

I am particularly grateful to Martin Coppers and Klaus-Michael Mallmann. The importance of their research and writing on Nazi Germany and the Middle East is evident in the text and notes of this book. Dr. Cuppers graciously shared his knowledge of the relevant files and offered comments on the manuscript. Thanks to David and Dawn Cesarani for their kind hospitality during my research in Britain's National Archives (NA) in Kew Gardens. Both the informative Web site of Britain's National Archives and the professional staff helped in locating files quickly.

I benefited greatly from the computerized ordering of files at the Political Archive of the German Foreign Ministry, the National Archives in Britain, the German Federal Archives in Berlin and Freiburg. Thanks are due to the archive administrators of the PAAA, NA, ZMO, and the United States National Archives for permitting the use of digital cameras in the archives. In so doing they are facilitating a minor revolution in the speed and reliability with which researchers can make copies of needed files at dramatically reduced costs.