The Complete Works of

PAUSANIAS

(c. AD 110 c. 180)

Contents

Delphi Classics 2014

Version 1

The Complete Works of

PAUSANIAS

By Delphi Classics, 2014

COPYRIGHT

Complete Works of Pausanias

First published in the United Kingdom in 2014 by Delphi Classics.

Delphi Classics, 2014.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form other than that in which it is published.

Delphi Classics

is an imprint of

Delphi Publishing Ltd

Hastings, East Sussex

United Kingdom

Contact: sales@delphiclassics.com

www.delphiclassics.com

The Translation

Ancient remains at Sardis, the capital of the Kingdom of Lydia Pausanias was most likely a native of Lydia

Other ruins at Sardis

DESCRIPTION OF GREECE

Translated by W. H. S. Jones

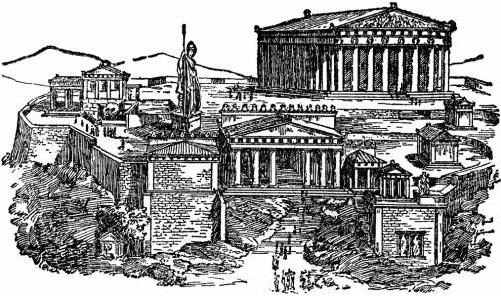

Composed in ten books, with each being dedicated to an area of Greece, Pausanias Description of Greece is an important surviving work that describes many lost wonders and archaeological features of ancient Greece from firsthand observations, serving as a crucial link between classical literature and modern archaeology. The great work commences in Attica, with Athens and its demes dominating the discussion. The subsequent books concern Corinth, Laconia, Messenia, Elis, Achaia, Arcadia, Boeotia, Phocis and Ozolian Locris. The Description of Greece functions largely as a cultural geography, where Pausanias often digresses from description of architectural and artistic objects to review the mythological and historical underpinnings of the society that produced them. As a Greek writing under the auspices of the Roman Empire, he found himself in an awkward cultural space, between the glories of the Greek past he was so keen to describe and the realities of a Greece partly in servitude to Rome as a dominating imperial force. For these reasons, the Description of Greece demonstrates the authors careful attempts to establish an identity for Roman Greece, which is distinctly its own.

Pausanias is particularly noted for his detailed descriptions of the religious art and architecture of Olympia and of Delphi. At Thebes he views the shields of those who died at the Battle of Leuctra, the ruins of the house of Pindar and the statues of Hesiod, Arion, Thamyris and Orpheus in the grove of the Muses on Helicon, as well as the portraits of Corinna at Tanagra and of Polybius in the cities of Arcadia.

In the topographical sections of his work, Pausanias is fond of digressions on the wonders of nature, including comments on the signs that herald the approach of an earthquake, the phenomena of the tides, the ice-bound seas of the north, and the noonday sun which at the summer solstice casts no shadow at Syene (Aswan). Though he never doubts the existence of the gods and heroes, he occasionally criticises the myths and legends relating to them. His descriptions of monuments of art are plain and unadorned, producing an impression of reality, with their accuracy confirmed by the extant remains. Pausanias is entirely open in his confessions of ignorance and when he quotes a book at second hand he takes pains to say so.

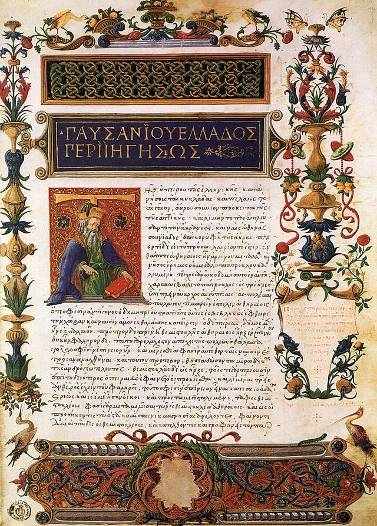

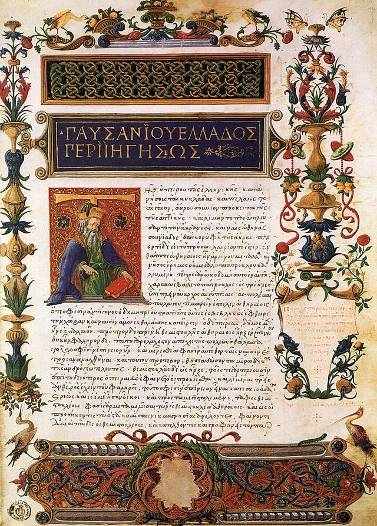

The work was largely ignored until the Middle Ages. We in fact came perilously close to losing it altogether, as only three manuscripts survive from 15th-century copies, with are troubled with errors and lacunae, which all appear to depend on a single manuscript that survived to be copied. Niccol Niccoli had this archetype in Florence in 1418 and following his death in 1437, the copy went to the library of San Marco, Florence and then disappeared after 1500. Until twentieth century archaeologists discovered just how reliable Pausanias was a guide to the sites that were being excavating, Pausanias was almost dismissed by previous classicists, who followed the authoritative Wilamowitz in discrediting him, as a purveyor of literature quoted at second-hand, who, it was suggested, had not actually visited most of the places he described. Habicht 1985 describes an episode in which Wilamowitz was led astray by misreading Pausanias, in front of an august party of travellers, in 1873, and attributes to it Wilamowitz lifelong antipathy and distrust of Pausanias. The experience of a century of archaeologists, however, has fully vindicated the reputation of Pausanias and his Description of Greece .

The 1485 manuscript of the Description of Greece, housed in the Laurentian Library

CONTENTS

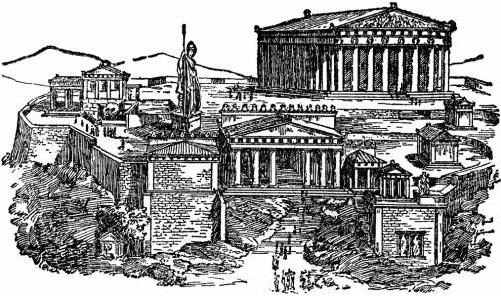

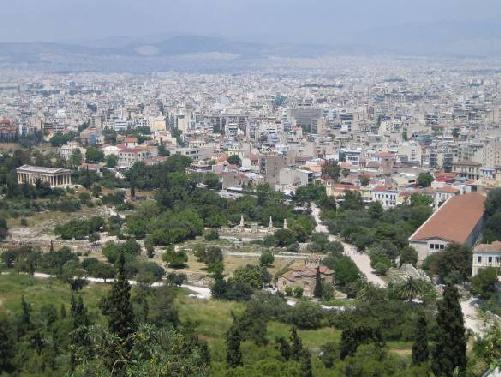

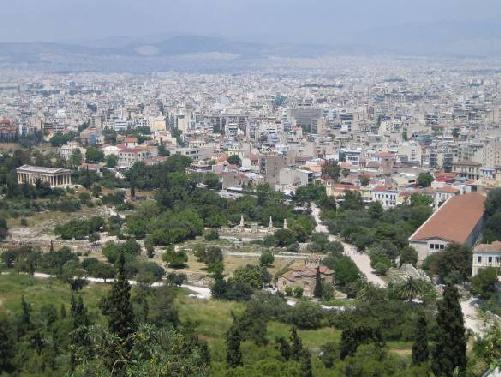

The Athenian Agora, features in Book I

Ancient Corinth, whoich features in Book II

PREFACE.

THE present work was originally intended to be a plain translation of the text of Spiro. After a time I was requested by the Editors of the Loeb series to add a few notes, dates, maps, etc., so that the Tour might be more intelligible to English readers. Fully aware of the difficulties and dangers of the plan, I have nevertheless tried my best to choose from a vast quantity of material just those scraps of information which an English reader would need most. A few of the notes are printed at the side and foot of the page; most of them, together with the maps and plans, are reserved for the Index, which it is hoped to make a companion to Pausanias.

The transliteration of Greek names has been a matter of difficulty. The only wav to avoid inconsistencies is to transliterate letter for letter without attempting either to Latinize or to Anglicize. To follow the rules adopted in the Loeb series without occasional inconsistencies is impossible, especially as the number of names given by Pausanias is so vast; here again I can only say that I have tried my best.

The text of Spiro has rarely been altered. A few of the most plausible conjectures, generally though not always adopted by Spiro, have been assigned to their authors in footnotes.

In my translation I have not distinguished between Medes and Persians, or Ilium and Troy. It is rather deceptive to an English reader to do so, and the Greek scholar can easily tell from the original which word in each case was used by Pausanias.

I have to acknowledge much kind help. Especially am I indebted to my friend Mr. A. W. Spratt, Fellow of St. Catharines College, for his careful reading of the proofs. Professor Ridgeway and my colleague, Mr. R. B. Appleton, have given invaluable criticism and advice.

Next page