Contents

Page List

Guide

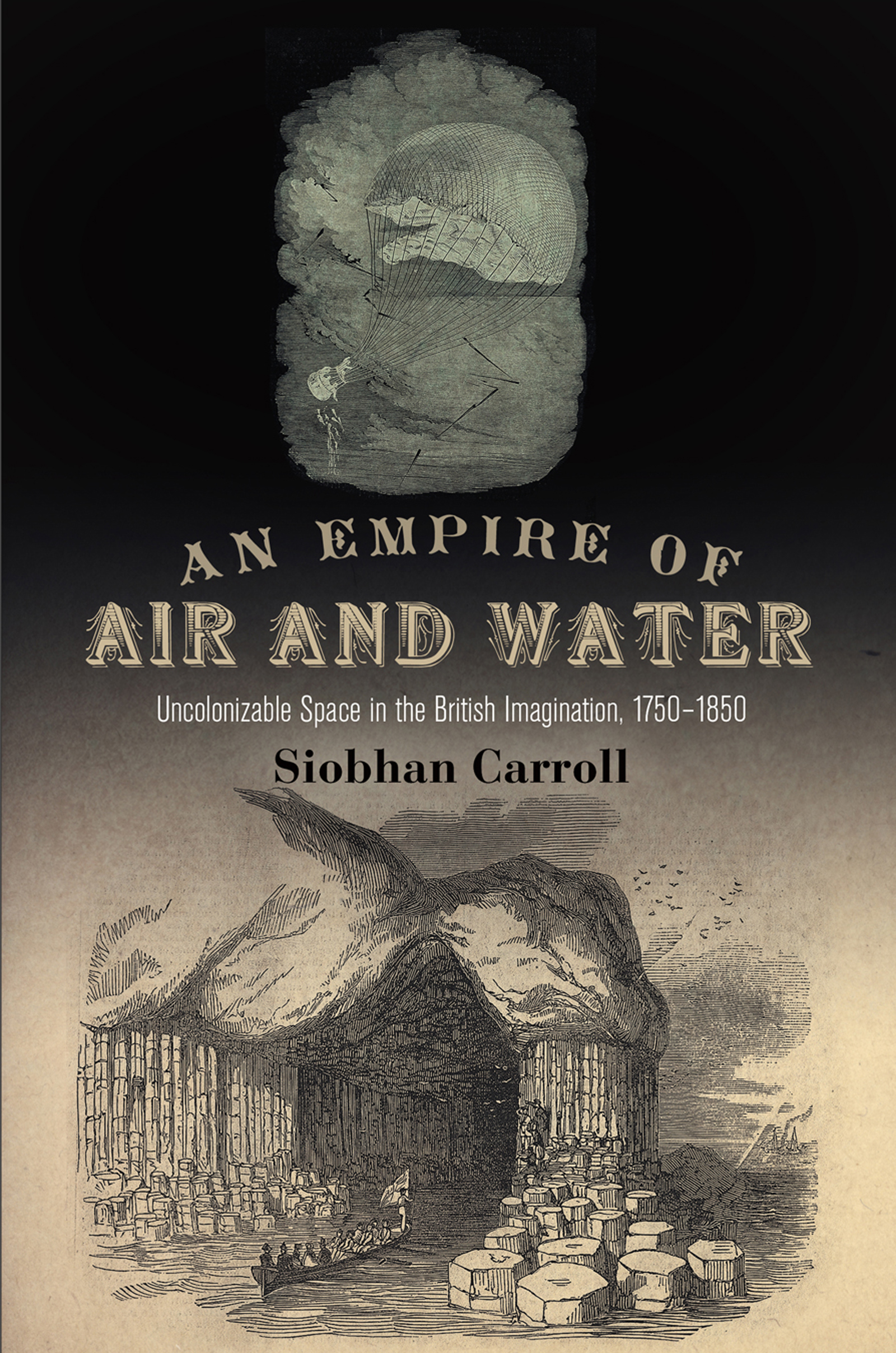

An Empire of Air and Water

AN EMPIRE OF AIR AND WATER

Uncolonizable Space in the British Imagination, 17501850

SIOBHAN CARROLL

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA PRESS

PHILADELPHIA

Copyright 2015 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Carroll, Siobhan.

An empire of air and water : uncolonizable space in the British imagination, 17501850 / Siobhan Carroll. 1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8122-4678-0

1. English literature18th centuryHistory and criticism. 2. English literature19th centuryHistory and criticism. 3. Space in literature. 4. Geography in literature. 5. Place (Philosophy) in literature. 6. Geography and literature. 7. Nationalism and literatureGreat BritainHistory18th century. 8. Nationalism and literatureGreat BritainHistory19th century. I. Title.

PR447.C37 2015

820.9'32dc23

2014028856

For my family, with love and appreciation

Contents

Introduction

Blank Spaces on the Earth

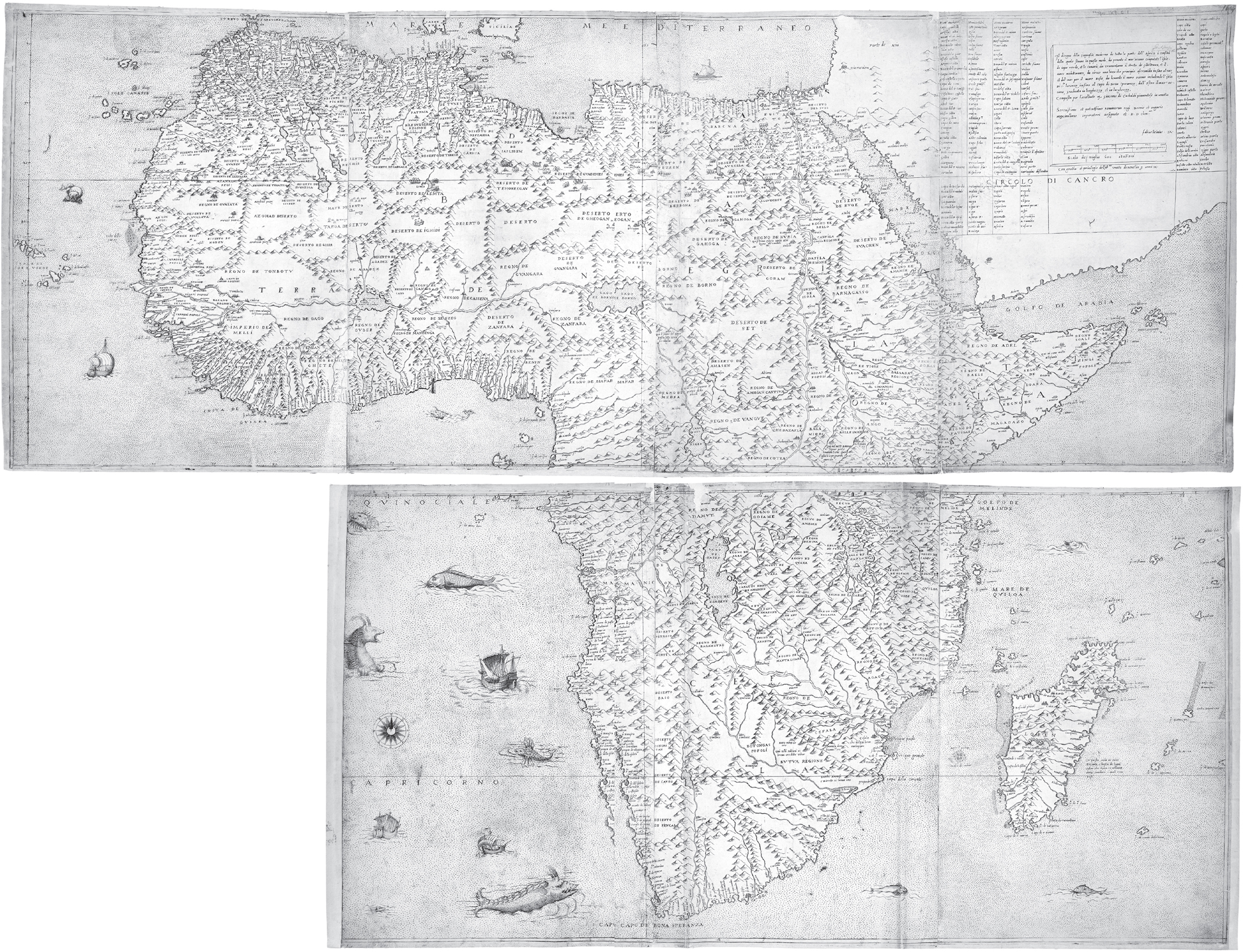

In 1749, Jean Baptiste Bourguignon dAnville erased the world. Born into a century full of elaborate illustrations of distant places, the French cartographer (16971782) became famous less for the beauty of his maps than for what they excluded: centuries of accumulated stories, maps, and travelers tales concerning distant places on the globe. As Alfred Hiatt observes, dAnvilles cartographical predecessors had followed the tradition of including mountain ranges, rivers, and tribes that were rumored to exist in spaces that had yet to be explored by Europeans, producing detailed maps of a world that was already known and merely awaited rediscovery: a world such as the one depicted in Giacomo Gastaldis (15001566) famed 1564 map of Africa (see

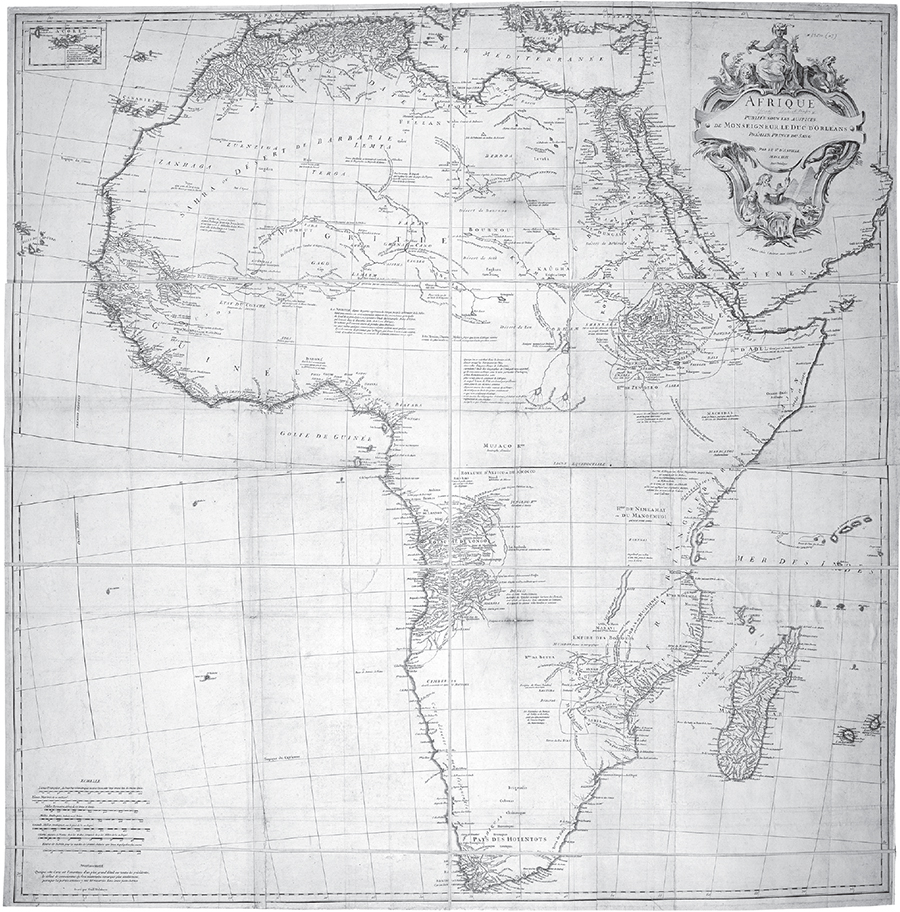

DAnvilles 1749 map of Africa, however, marked a decided shift away from the world of the ancients (see

DAnville defended his use of blank space by referring to French Enlightenment historiography, which, as Voltaire would argue, proposed to eliminate all the fables with which fanaticism, the romantic spirit and credulity have at all times peopled the theatre of the world.

Figure 1. Giacomo Gastaldi, Il disegno della geografia moderna de tutta la parte dell Africa (Venice, 1564). The British Library Board. Maps 189.C.I. Note that the interior of Africa, which at the time European explorers had yet to penetrate, is depicted as thoroughly mapped.

Figure 2. Jean Baptiste Bourguignon dAnville, Afrique (Paris, 1749). The British Library Board. Maps * 63510.(47)

As J. B. Harley has argued, the silences of blank space had social consequences. DAnvilles blank spaces replaced visions of populated territory with a visual terra nullius, a no persons land invitingly open for colonial appropriation. And dAnvilles map also erases stories: the details gleaned from centuries of speculation concerning the African continent. In their place, we are presented with empty paper, which on one hand tantalizes us with the promise of future inscriptionwe, too, can write on this map; there is now space for us to do sobut on the other hand testifies to the fragility of fiction in the face of the Enlightenments pursuit of knowledge. The Africa of dAnvilles map is no longer occupied by polyphonic tales of monsters and strange peoples: There is, the map asserts, only one master narrative of African space. There is only one Africa, and dAnvilles map is the authoritative voice on what it contains.

The publication of dAnvilles 1749 map marks a seminal moment in the history of European spatial thought, and it provides a useful starting point for examining the impact of a new phase of state-sponsored exploration and cartographical representation on geo-imaginary spaces. DAnvilles erasure of story points us to some of the tensions inherent in the rise of scientific cartography, indicating not only the colonial ramifications of this new era of exploration, but also the challenge posed to fiction makers, as areas previously open to all types of speculation now appeared roped off to all but the most realistic representations. When we see British authors such as Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and Sophia Lee attempting to set limits on the nation-states penetration of blank spaces, I suggest, it is in part because the literary imagination itself can appear threatened by such expansion.

This book takes as its subject not the blank space of continents like Africawhich, as Joseph Conrads Marlow notes in Heart of Darkness, was destined not to remain blank at all but to become a place of darkness, dark with the ink depicting European claims, black with the names of colonial venturesbut a set of spaces that, even into the early twentieth century, retained their association with blankness. On global maps, areas such as the poles, the ocean, the atmosphere, and the subterranean were either depicted as mostly empty spaces or evaded such representations altogether. They were imagined as harboring within themselves marvelous unknowns such as the deep sea and the inner earth, but also as resisting, because of their climate or material character, their conversion into colonizable forms of space. On one hand, these atypical spaces often played an important role in imperial ideologies, recognized, in the case of the ocean, as the foundational space of Britains maritime empire, and depicted, as in the case of the poles, as spaces illuminating Britains national character. But on the other hand, these spaces were also perceived as challenging imperial ambitions by virtue of their intrinsic resistance to cultivation and settlement and, thus, to territorial appropriation and state control.

As Carl Schmitt observes of the sea in The Nomos of the Earth, certain spaces exist outside the terrestrial orientations of the great primeval acts of law appropriating land, founding cities, and establishing colonies; even in Schmitts own day, they are not considered to be state territory.

As spaces presumed to lie at or beyond the fringes of everyday life, atopias dialectically construct the inhabited places of home and community, providing a contrast to the familiarity, stability, and security implied by idealized sites of dwelling. Unlike the wilderness of Turners frontier, the unsettling nature of atopias is imagined as a permanent affair: They await neither improvement, nor inevitable wide-scale settlement, nor seamless incorporation into the domestic space of the nation. To voyage too far or stay too long in an atopia is considered hazardous, a perception reinforced in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries by explorers descriptions of the bodily disintegrations they experienced in such regions: blackouts, snow-blindness, scurvy, madness, suffocation, and poisonings. And to be rendered