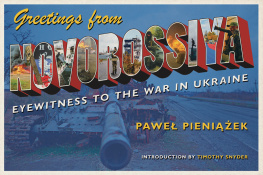

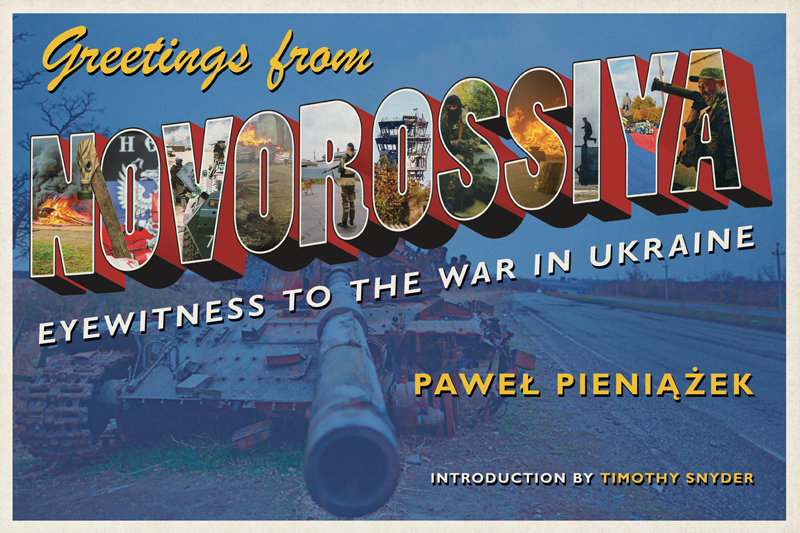

INTRODUCTION

TIMOTHY SNYDER

THE YEAR 1989, the year the Polish war reporter Pawe Pieniek was born, was understood by some in the West as an end to history. After the peaceful revolutions in Eastern Europe, what alternative was there to liberal democracy? The rule of law had won the day. European integration would help the weaker states reform and support the sovereignty of all.

But was the West coming to the East or the East to the West? By 2014, a quarter century after the revolutions of 1989, Russia proposed a coherent alternative: faked elections, institutionalized oligarchy, national populism, and European disintegration. When Ukrainians that year made a revolution in the name of Europe, Russian media proclaimed the decadence of the European Union (EU), and Russian forces invaded Ukraine in the name of a Eurasian alternative.

When Pieniek arrived in Kiev in November 2013 as a young man of twenty-four, he was observing the latest, and perhaps the last, attempt to mobilize the idea of Europe in order to reform a state. Ukrainians had been led to expect that their government would sign an association agreement with the European Union. Frustrated by endemic corruption, many Ukrainians saw the accord as an instrument to strengthen the rule of law. Moscow, meanwhile, was demanding that Ukraine not sign the agreement with the EU but instead become a part of its new Eurasian trade zone of authoritarian regimes.

At the last moment, Russian president Vladimir Putin dissuaded the Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych from signing the EU association agreement. The Russian media exulted. Ukrainian students, who had the most to lose from endless corruption, gathered on November 21 on Kievs central square, the Maidan, to demand that the agreement with the EU be signed. Pieniek arrived a few days later. After police beat the students on the night of November 30, the young men and women were joined by hundreds of thousands of others, people who would brave the cold, and worse, for the next three months.

The Euromaidan, as the protests were called at first, was multicultural and anti-oligarchical. Ukrainians were taking risks for a local goal that is hard to understand beyond the post-Soviet setting: Europeanization as a means to undo corruption and oligarchy. By enriching a small clique, writes Pieniek in this collection of his reportage from Ukraine, Yanukovych brought the state to the brink of actual collapse. In December 2013 Russian leaders made financial aid to Yanukovychs government contingent upon clearing the streets of protesters. The governments subsequent escalation of repressionfirst the suspension of the rights to assembly and free expression in January 2014 and then the mass shooting of protesters in Februaryturned the popular movement into a revolution. On February 22, Yanukovych fled to Russia. (Two years later his political strategist, Paul Manafort, would resurface in the United States, playing the same role for Donald Trump.) After the failure of its policy of repression by remote control, Russia invaded Ukraines Crimean peninsula. By March Russians who had taken part in that campaign were arriving in the industrial Donbas region of southeastern Ukraine, Yanukovychs onetime power base, to help organize a separatist movement.

Inhabitants of southeastern Ukraine had just as much reason to be dissatisfied with corruption as anyone else, and it was reasonable to fear that the revolution in Kiev was nothing more than a swing of the pendulum from some oligarchs to others. Just how these sentiments might have been resolved through negotiations or elections we will never know, since the Russian intervention precluded both, bringing instead fear and bloodshed that changed everyones political calculations.