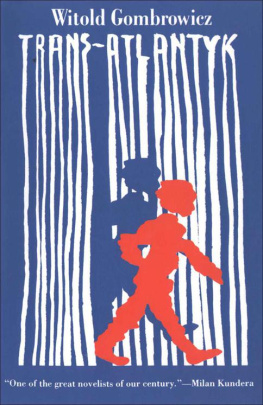

Gombrowicz Witold - Polish Memories

Here you can read online Gombrowicz Witold - Polish Memories full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: New Haven, year: 2004, publisher: Yale University Press, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Polish Memories

- Author:

- Publisher:Yale University Press

- Genre:

- Year:2004

- City:New Haven

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Polish Memories: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Polish Memories" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Polish Memories — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Polish Memories" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Polish Memories

Witold Gombrowicz

Translated by Bill Johnston

Copyright 2004 by Rita Gombrowicz.

Polish-language edition, Wspomnienia Polskie, published 2002

by Wydawnictwo Literackie.

Translation copyright 2004 by Bill Johnston.

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part,

including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted

by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except

by reviewers for the public press), without

written permission from the publishers.

Designed by Nancy Ovedovitz

Set in Minion type by Integrated Publishing Solutions.

Printed in the United States of America by R. R. Donnelly & Sons.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gombrowicz, Witold.

[Wspomnienia polskie. English]

Polish memories / Witold Gombrowicz ; translated by Bill Johnston.

p. cm.

ISBN 0-300-10410-3 (alk. paper)

1. Gombrowicz, Witold. 2. Authors, Polish20th centuryBiography.

I. Johnston, Bill. II. Title.

PG7158.G6692A38713 2004

891.8537dc22 2004014633

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability

of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity

of the Council on Library Resources.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Polish Memories

I was born and raised in a most respectable home: This ironic sentence, which begins one of my short storiesThe Memoirs of Stefan Czarnieckimay also serve as an opening for these present recollections. I was indeed a milksop from a so-called respectable family, but here the word respectable should be used without irony, since it was a home of people who generally speaking were kind-hearted and had their principles.

My father owned a small property in Sandomierz province and also worked in industry; when I was growing up he was president of Central Salvage and a member of several supervisory committees and governing boards, which guaranteed him an income considerably greater than that produced by tiny Maoszyce. My mother was the daughter of Ignacy Kotkowski, a local landowner. My father was originally from Lithuania; my grandfather, Onufry, had had his property confiscated by the Russian government in 1863, and this led him to move to the Kingdom, where with the little money he had managed to hold on to he bought the village of Jakubowice, and then a second, Maoszyce, where I was born.

We Gombrowiczes always regarded ourselves as rather better than the landed gentry of the Sandomierz region, particularly because of various family connections that had remained from the times in Lithuania, and also because the Lithuanian gentry, richer and settled for centuries on their possessions, could boast of a better tradition, a more detailed history, and more respectable appointments. Im not convinced, though, that the Sandomierz gentry shared this point of view. I was the youngest child. Janusz was the oldest, then came Jerzy, and then my sister, Irena, who was two years older than I was.

My life in Poland was uneventful and unchanging; I knew few exceptional people and had few adventures. But Id like to show, though I do not know whether it will be of use to anyone, the way in which life shaped meme and my literature. Naturally this will be very much an incomplete testimony, which will often remain on the surface of events, because this is not the place for more exhausting analyses or more ruthless confessions; yet I believe that even this toned-down biography will shed a small ray of light on the realities of Poland in those days. It would also be good if at the same time I were able to convey how today I regard the Poland of that timefrom a perspective of twenty years spent abroad, a western, American perspective.

In Poland I think that only a few people know me from an extensive reading of my books, which are admittedly somewhat difficult and eccentric. There are more who have heard of me; for them I am above all the author of the mug and the bum; its through these two powerful myths that I have entered Polish letters. But what does it mean to give someone a mug or to fix a bum on him? To give someone a mug is to lend someone a different face than his own, to distort him. For instance, when I treat a wise person as a fool or impute criminal intentions to a good person, I give them a mug. And fixing a bum on someone is in fact an identical operation, the only difference being that in this case an adult is treated like a child, infantilized. As you can see, both these metaphors are connected with an act of deformation that one person commits upon another. And if I have occupied a separate place in our literature, it is perhaps above all because Ive highlighted the extraordinary significance of form in both social and personal life. One person creates the otherthis was my psychological starting point. I believe, too, that my sensitivity to form from earliest childhood allowed me later to find my own literary style and to create a genre that today is slowly acquiring adherents around the world.

Yet where did I get it, this sensitivity to human formin other words, to a persons way of being? Once, before the war, in a lecture on my novel Ferdydurke the brilliant Polish artist Bruno Schulz said that this book was not made up, that it must have been the product of many difficult personal experiences. Schulz was not mistaken. In my own way I suffered considerably in the very early days of my existence; we shall speak at first of those torments of the Polish process of coming into being, in order later on to touch on other topics.

I shall begin from the fact that, appearances to the contrary, my family home was one immense dissonance constantly rending my childs ears. There were many reasons for this state of affairs; one of the most important was the incompatibility in temperament and character between my mother and my father.

My father, a handsome, dapper mana thoroughbred as people would emphasize in those dayswas considered serious, responsible, and honest. The contrast between his proper and dignified behavior and certain eccentricities manifested by us, his sons, produced many a reaction along the lines of what would your father have to say about that, or what a pity they didnt take after old Gombrowicz. His impeccable appearance, in combination with a mind that was neither particularly profound nor had especially wide horizons, yet which worked efficiently, secured for my father those mostly symbolic positions on various committees and boards.

My mother, on the other hand, was distinguished by an uncommonly lively nature and a fertile imagination. She was nervous, extravagant, inconsistent; she had no self-control. She was naive and, worst of all, had the most mistaken image of herself. Father often succumbed to her quick-wittedness and intelligence, but more often endured in silence her various exaltations, which were indeed hard to handle.

I dont wish to dwell overlong on my closest family. I will say that, in my view, it was my mother who introduced into our home the profound formal ambiguity within which I grew up. I dont blame her for this, since she had a noble character and the best of intentions, and she was exceedingly fond of us; but, despite her excellent command of French, various kinds of knowledge that constituted the education of a young lady of the gentry, and firm moral principles, she lacked that which gives an ordinary milking-girl such self-confidence, naturalness, and straightforwardnessshe hadnt been tested by life. She had never really come into contact with it. This was what deprived her of authority in our eyes and meant that she moved about in a vacuum.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Polish Memories»

Look at similar books to Polish Memories. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Polish Memories and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.