Thirteen friends purchase bus tickets to New Orleans, Louisiana. They plan to reach that city on May 17 to help celebrate the seventh anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Courts Brown v. Board of Education decision. They are men and women, young and old, black and white. They are people with a plan. They chat quietly, nervously, excitedly. They are prepared for the unexpected.

For Cindy Clevenger and Kathleen Krull, with thanks

Text copyright 2017 by Larry Dane Brimner, Trustee or his Successors in Trust, under the Brimner-Gregg Trust, dated May 29, 2002, and any amendments thereto.

All rights reserved.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

please contact .

Calkins Creek

An Imprint of Highlights

815 Church Street

Honesdale, Pennsylvania 18431

Printed in China

ISBN: 978-1-62979-586-7 (hc) 978-1-62979-917-9 (e-book)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017937780

First edition

H1.0

Designed by Barbara Grzeslo

Titles set in Impact

Text set in Courier Bold and Adobe Caslon

LANDMARK

EVENTS BEFORE

THE TWELVE DAYS

IN MAY

Plessy v. Ferguson (1896)

On June 7, 1892, Homer Plessy, a light-complexioned black man, deliberately sat in the white-only car of the East Louisiana Railroad. He identified himself as Negro and was arrested for violating Louisianas Separate Car Act, passed in 1890. The act segregated railroad passengers by race. Plessy wanted to test the law, and his case eventually reached the U.S. Supreme Court. The court ruled that separate facilities for blacks and whites were constitutional as long as they were equal. This separate-butequal doctrine eventually was applied to all areas of liferestaurants, theaters, schools, waiting rooms, restrooms, and even drinking fountains. The facilities for blacks were never equal.

Morgan v. Commonwealth of Virginia (1946)

Irene Morgan, a black woman, boarded a bus going from Virginia to Baltimore, Maryland. She was ordered to sit in the back of the bus. She objected, saying the laws and the Constitution of the United States, not Virginia segregation laws, applied since the bus was an interstate bus (one that crossed state boundaries). She was arrested and fined $10, but Morgan took her case to the Supreme Court. The court ruled in Morgans favor. The laws of one state cannot extend beyond its borders. To avoid a patchwork of regulations in which some states racially segregated passengers and others did not, the court saw a need for a single, uniform rule for interstate passengers. Segregated seating on interstate buses was declared unconstitutional, but the courts ruling did not apply to buses traveling only within a state.

Separate-but-equal was the law of the land following the U.S. Supreme Courts Plessy decision, but accommodations for blacks were always inferior, never equal.

Brown v. Board of Education (1954)

In 1954, a large portion of the United States had segregated schools as a result of the Plessy decision. A black third-grader in Topeka, Kansas, named Linda Brown would help bring an end to the separate-but-equal doctrine established in Plessy. Linda could not attend the white-only school just six blocks from her house. She had to catch a bus to attend a segregated school a mile away. Oliver Brown, Lindas father, filed a lawsuit. But it was later combined with other cases making their way to the Supreme Court. The Browns and other plaintiffs claimed that racially segregated schools violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution. The Equal Protection Clause requires states to treat individuals equally under the law. In its landmark decision, the Supreme Court unanimously declared that separate-but-equal has no place in the field of public education because to separate is to make unequal.

At their black-only school, children gather to warm themselves around a stove in their classroom. Black youngsters relied on tattered, used textbooks and supplies handed down from schools for whites.

Boynton v. Virginia (1960)

In 1958, Bruce Boynton, a black Howard University law student, boarded a bus in Washington, D.C., bound for Montgomery, Alabama. In Richmond, Virginia, the bus stopped briefly so passengers could eat. Boynton went into the terminal restaurant and sat in the white-only section. When told to move, he refused, was arrested, and fined $10. He took his case to the Supreme Court. The Morgan decision had ruled that racial segregation in interstate transportation was unconstitutional. Now in Boynton, the court extended its ruling, declaring that segregation among interstate passengers at bus station facilitiesrestaurants, lunch counters, waiting rooms, and restroomsalso violated the law.

Young students, black and white, from six Texas schools protest segregation in 1949.

THE SIT-INS

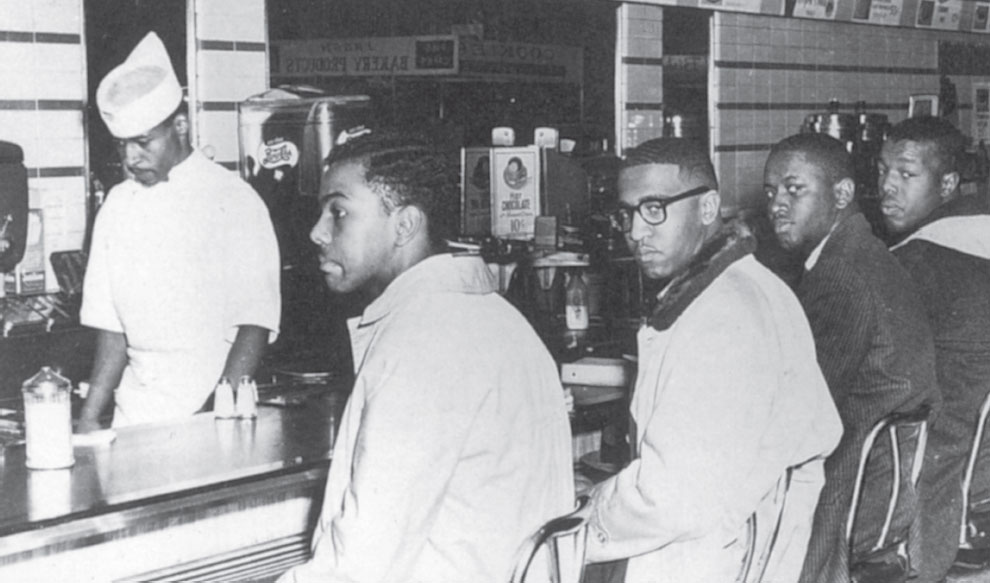

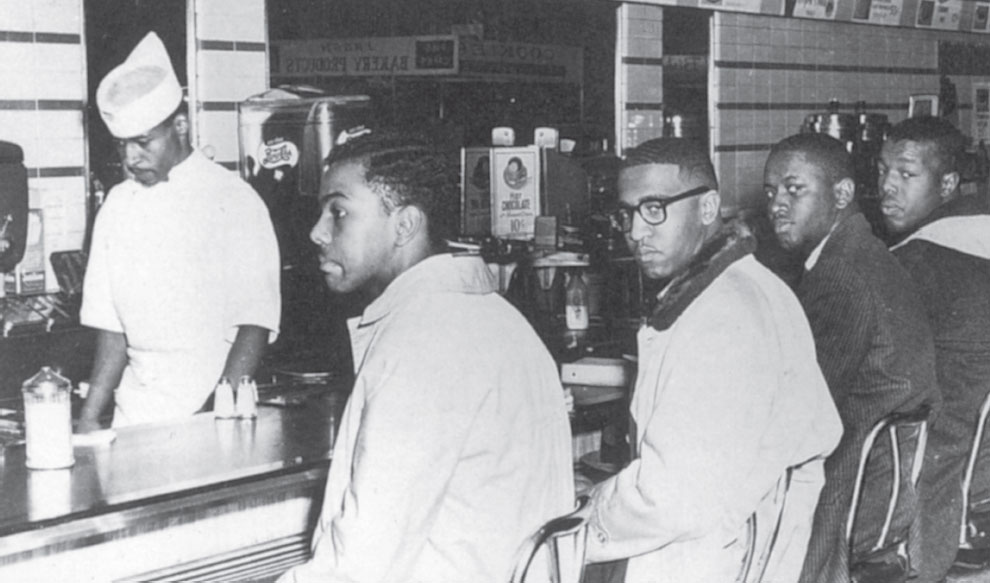

In February 1960, four black students from North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University took seats at the local Woolworths white-only lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina. They politely ordered coffee, but they were refused service and asked to leave. When they told their classmates about what had happened, the local protest grew in size. Within two months, more than seventy thousand young peopleblack and whitein fourteen states were conducting sit-in campaigns. The protests eventually spread throughout the United States wherever discrimination was practiced.

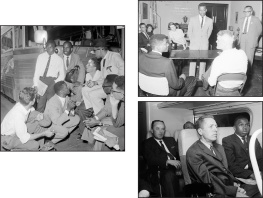

The Greensboro, NC, sit-ins began when David Richmond, Franklin McCain, Ezell Blair Jr. (known now as Jibreel Khazan), and Joseph McNeil sat down on February 1, 1960, at Woolworths white-only lunch counter and waited for service. (Press photographers were not allowed into the store the first day of the demonstration.) On the second day of the peaceful protest, McNeil (seated, from left) and McCain are joined by Billy Smith and Clarence Henderson, and more than a dozen others as the sit-in movement grew.

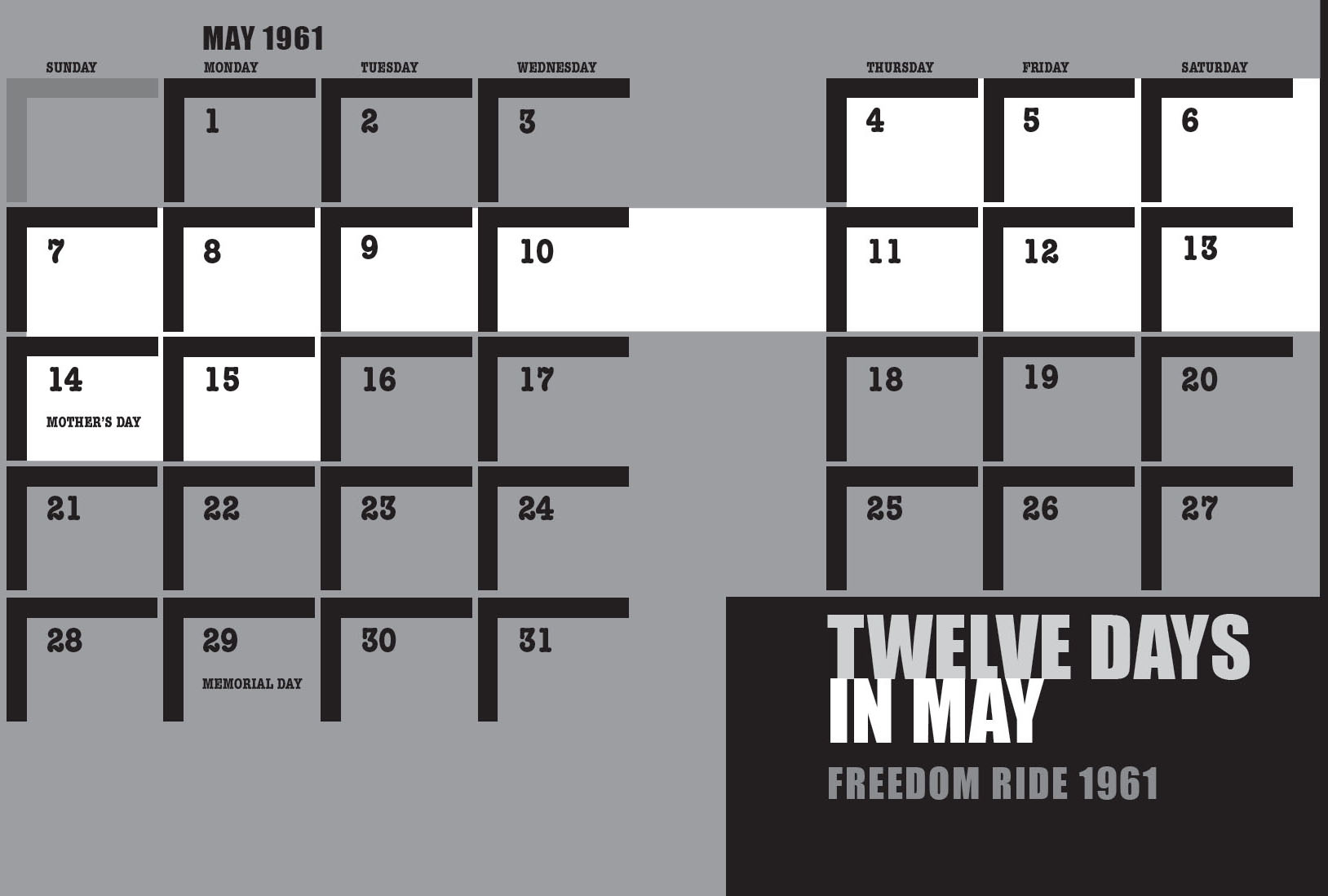

MAY 1961

SUNDAY | 14

MOTHERS DAY | | |

MONDAY | | | 29

MEMORIAL DAY |

TUESDAY | | | | |

WEDNESDAY | | | | |

THURSDAY | | |

FRIDAY | | |

SATURDAY | | |

TWELVE DAYS

IN MAY

FREEDOM RIDE 1961