The author and publisher have provided this ebook to you for your personal use only. You may not make this ebook publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this ebook you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at:us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

The arms of mothers are made of tenderness; in them children sleep profoundly.

Victor Hugo

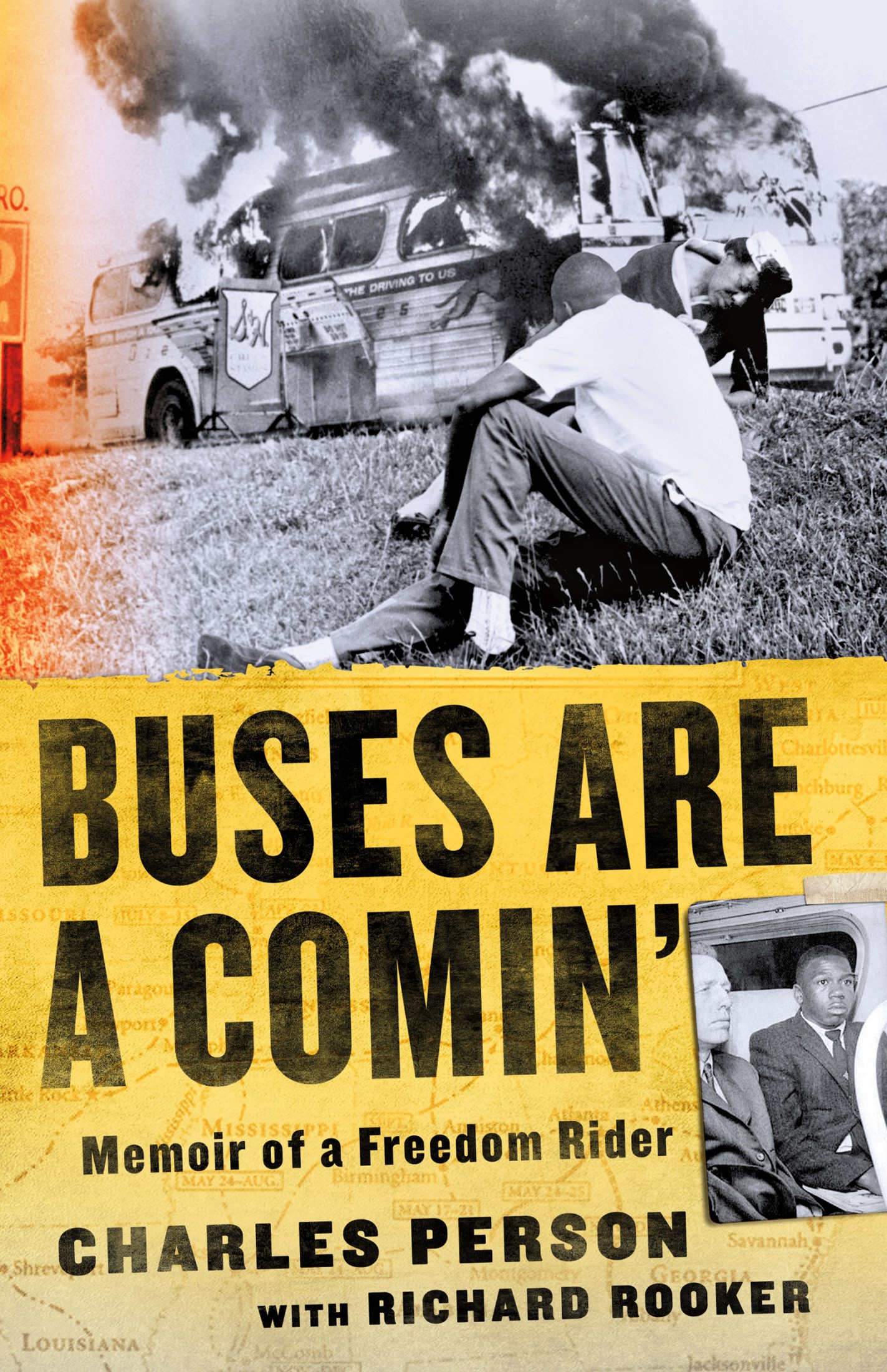

Lets burn them niggers alive. Lets burn em alive, the voice said.

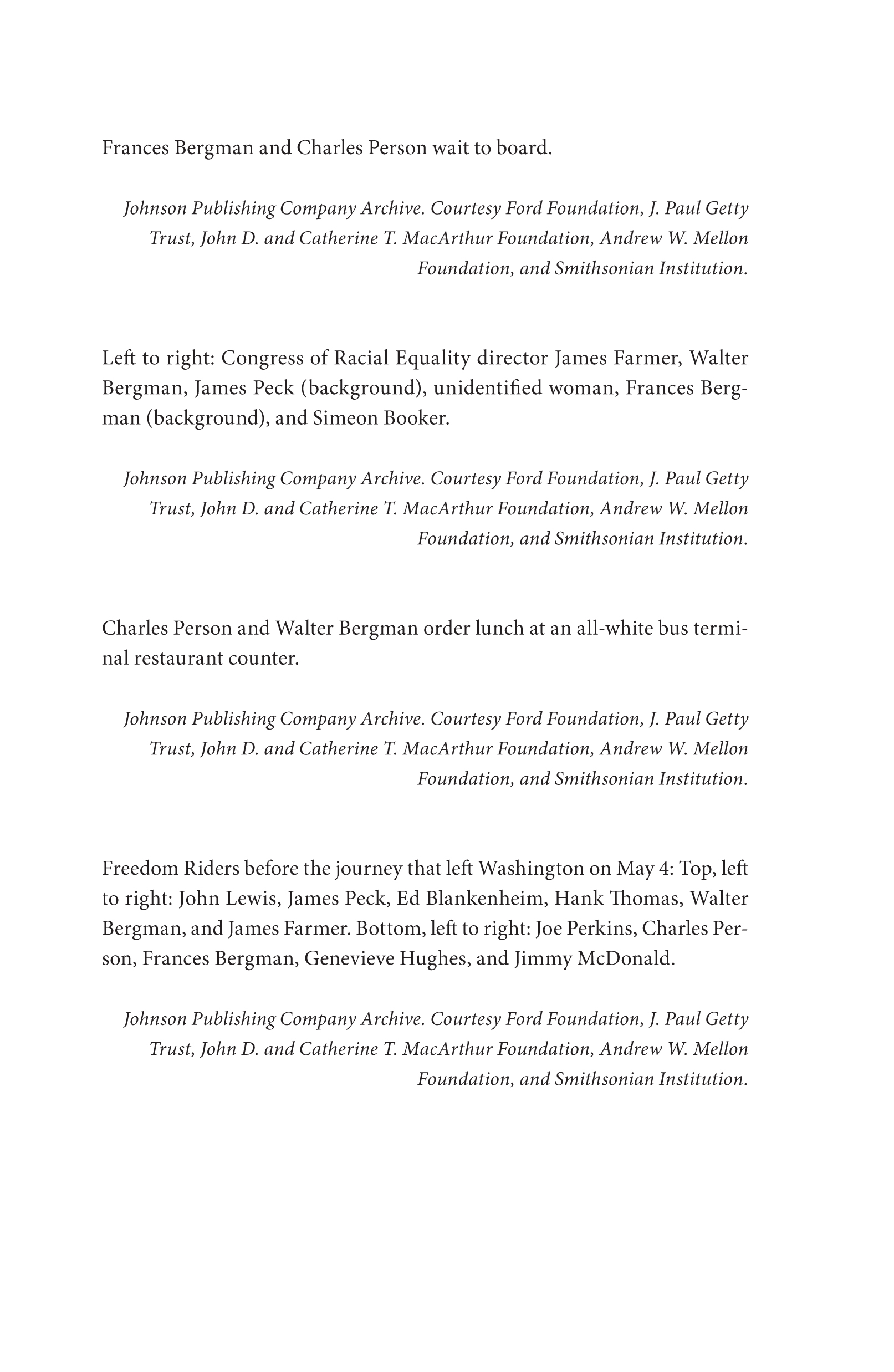

Strong arms held the door of a burning bus closed from the outside. Angry men shouted vile words to the black and the white passengers sitting side by side in the busthe Greyhound bus traveling from Washington, D.C., to the Deep South through the Bible Belt. The passengers heard the hatred, saw the enmity, felt the venom. Panic mixed with resignation. Panic. No escape apparent. If escape were possible, the route out would lead to men bent on murder. Resignation. So, this is how life ends. With last breaths being smoke, not air.

If we got off of that bus, remembered my friend Hank Thomas, there was no doubt in my mind we would have been killed. I decided that the best way to die was by taking a big gulp of poisonous smoke. I thought that would put me to sleep, and thats the way I was going to die.

It was 2:00 P.M., Sunday, May 14, 1961, in Anniston, Alabama.

Two hours later, sixty miles to the west in Birmingham, Alabama, dozens of angry arms and fists and knuckles surrounded and beat a man. In his infancy that man had slept profoundly in the tenderness of his mothers arms. His black mothers arms. It was now white arms of power and violence attacking him. Hadnt those men, too, slept profoundly in their mothers tender arms?

Years earlier Birminghams commissioner of public safety had proclaimed, Damn the law. We dont give a damn about the law. Down here we make our own law. He had assured those bent on hate and violence they could have fifteen uninterrupted minutes this day to do whatever they wanted to the unwanted Black bus riders and their white companions before he and his police force would intervene. Had not the commissioner of public safety also known the tender arms of his mother?

Mothers wrap their babies in blankets and love. They protect them from danger. They gaze into their innocent eyes and see kindness. They stare into their imagined futures and see promise. It is a rare mother who holds her infant in her tender arms and awaits with eager anticipation the day her child will hold a burning buss door closed trapping people inside, who foresees with hopefulness a bludgeoning, or who dreams of her child having thoughts beginning with the word Damn.

Because a mothers love is like no other, we give mothers a day like no other: Mothers Day. Today, we celebrate Mothers Day with store-bought cards, bouquets of flowers, gourmet chocolates, and meals at nice restaurants. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Mothers Day to me meant making a homemade card and giving Mom a hug. At best, I might give my mom a dainty hanky that cost pennies. When a parent brings home $40 to $50 a week, flowers, chocolates, and restaurants are not on your Mothers Day mind. But whatever the year, wherever the place, we want Mothers Day to be a memorable day.

On the most memorable Mothers Day of my life, arms held a burning buss door closed. My friends and colleagues, such as Hank Thomas, were on that bus in Anniston.

On that Mothers Day in Birmingham, a circle of anger and hatred rained down fists, feet, and clubs on a black man. I was that black man. And Eugene Bull Connor was the commissioner of public safety who assured members of the Ku Klux Klan he would not interfere with their violence for a quarter of an hour.

The year 1961 began with optimism and hope. On January 20, the youngest man elected president in our nations history took the oath of office. Forty-three-year-old John F. Kennedy opened his inaugural address by calling the day a celebration of freedom.

Folks such as me were not feeling all that free. But President Kennedys words inspired usinspired mebecause a moment later he said, United there is little we cannot do.

Make no mistake, the young black people who wanted to bring change to the Southern way of life were united. And in our youthful exuberance and our hopeful optimism, we believed there was little we could not do.

The new president said that day, The energy, the faith, the devotion which we bring to this endeavor will light our country and all who serve it. And the glow from that fire can truly light the world.

Well, we in the Movementbe it the Atlanta Student Movement or the Civil Rights Movementhad energy, had faith, had devotion. In abundance. We believed. We believed we could spark a fire that would be a light unto the country and the world.

In his most famous line President Kennedy challenged us: And so, my fellow Americans, ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country.

In 1961, we answered that challenge. We fulfilled that call. We did something for our country.

We took to the streets, the establishments, the institutions, the parks, and the playgrounds where we were not welcomed. We made a demand to be seen, acknowledged, heard, and affirmed as human beings. We sat in at restaurants, kneeled in at churches, and waded in at beaches where human beings who somehow thought they were more human than we met us with force, indignation, mockery, and arrest. We sought to educate those who had little tolerance and no acceptance of the idea that because the Declaration of Independence had declared all men are created equal, it was more than time to think those words included us. We marched down streets. We got arrested. We went to jail for our beliefs. We did this because the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution told us all persons born in the United States are citizens of the United States. But we were not being treated the way other citizens were.

We asserted our humanity because it galled us that white men in our communities had not only been cradled in the loving arms of their mothers, but had also been cuddled in the caring arms of black nannies and domestics rearing them as they would rear their own children. Now as adults those former innocent babies held a bus door closed and pounded on people who sought to do something as simple as ride a bus. Might it have been possible that a woman who had held one of those attackers as an infant in her loving arms was now being trapped by the door they held shut? Would they have cared if she had been?