The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

Foreword

The only encouragement we hold out to strangers are a good climate, fertile soil, wholesome air and water, plenty of provisions, good pay for labor, kind neighbors, good laws, a free government and a hearty welcome.

These words were spoken by Benjamin Franklin, who did so much to promote the American cause of independence, a hundred years before the Famine Emigration. But they held true for a million and more citizens of Ireland, the men, women and children who sailed to America between 1846 and 1851, so that they might escape the Famine and survive. For as little as US $10, a passenger could sail 3,000 miles across the Atlantic Ocean, a voyage of fear, hunger, sickness, misery and hope. But a million more would die at home, from starvation and fever, after the failure of the potato crop in successive seasons.

Were those voyagers alive today, what stories they could tell, of the agonizing decision to leave their beloved Isle of Erin, of the lamentions on their last night at home and the American Wake, as it came to be known, of the arduous journey to the port and the search for a ship, of the misery they endured on the voyage! But what joy when they arrived, what relief they must have savoured as they stepped ashore! They were released from tyranny, no longer tormented tenants. Free at last, they could start to live again.

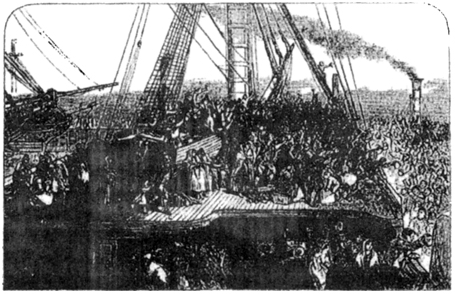

A famous drawing from the Illustrated London News, July 6th 1850, The Departure.

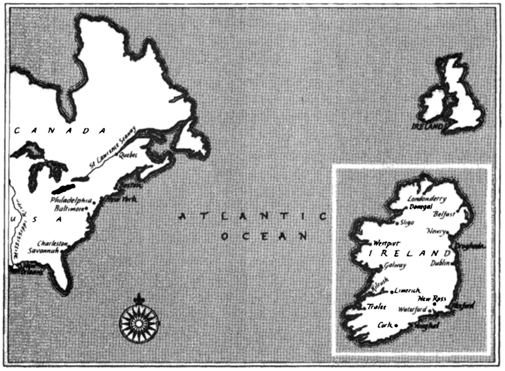

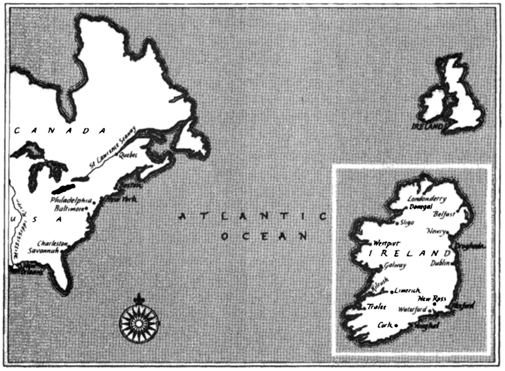

In fact emigration from Ireland to America had begun in the early 1700s. A trickle swelled to an average of 5,000 a year by 1830 and grew steadily until the Famine arrived and the exodus began, 150 years ago. The emigrants sailed to New York and Boston, to Philadelphia, Baltimore and New Orleans, and they spread across Americas heartland. They sailed to Canada, a British colony to which the passage was cheaper, from where an estimated 200,000 immediately went south across the border.

Before the Famine the population of America had risen to around 23 million. The Statue of Liberty, with its famous welcome for immigrants, was not yet built Ellis Island was many years away. But the Irish looked upon America as their natural choice and by 1850 the residents of New York were 26 per cent Irish.

Seven million are believed to have left Ireland for America over the last three centuries. For a million, over a period of six years, there was no option. Now more than 40 million American citizens can claim Irish blood.

While books on the Famine period have dealt with the journey, no publication has dealt specifically with the Irish-owned ships, the Irish crews who sailed them, the Irish ports they sailed from and the Irish passengers they carried in those years.

The ships featured in this book made these crossings on the dates shown, at the times stated; passenger lists are from US Immigration files, crews papers for the specific voyages from marine archives, and a wealth of first-hand reports have contributed to the stories. Details have been taken from eyewitness accounts; original Certificates of Registration, paintings and contemporary lithograph drawings have been reproduced.

SOURCES: National Library, Dublin; Linen Hall Library, Belfast; American-Ulster Folk Park; Famine Museum, Strokestown, County Roscommon; Royal Maritime Museum, Greenwich; Liverpool Maritime Museum; Public Record Office and Guildhall Library, London; the libraries of Cork, Cobh, Galway, Limerick; the Bodleian and Rhodes House Libraries, Oxford; Irish Historical Society, New York; Balch Institute and Maritime Museum, Philadelphia.

Introduction: These Desperate People

For 700 years prior to the Great Famine, the Irish had gradually become a nation of tenants in their own homeland. Irelands estates and farms were continually seized and redistributed by their oppressors, the invading armies and the avaricious kings and noblemen of England. The land was let and sub-let, divided and sub-divided, often to be rented and worked by the original owners. In 1841 a census revealed that the population of Ireland had peaked at just above 8 million. Fully two-thirds of those depended on agriculture for their survival, but they rarely received a working wage in return for the patch of land they needed to grow enough food for their own families.

The rich maintained their wealth through ownership of the land and wielded the political power in Ireland, yet a number of the absentee landlords living in England had never set foot in Ireland. They extracted profitable rents from their impoverished tenants or paid them minimal wages to raise crops and livestock for export. This was the system which forced Ireland and so many of her people to rely on a single crop, and only the potato could be grown in sufficient quantity on these tiny scraps of soil.

The rights to a piece of land meant the difference between life and death in Ireland in the early 1800s. The population was exploding, and with hundreds of thousands without work, entire families managed to exist on a section no bigger than half an acre, growing nothing more than row after row of potatoes. If they were lucky, they might have enough land to raise a pig each year, to slaughter, salt and eat through the worst of the winter months. They might go hungry for a few weeks at the end of the summer, when the previous seasons potatoes were no longer edible, but what was the alternative?

There were famine years before the blight struck and the English rulers were well aware of the problems arising out of the economic structure they had forced on the Irish. During the first 45 years of the last century at least 150 committees and commissions of inquiry, appointed by the British Parliament, had made their reports on the State of Ireland. But nothing happened.

Emigration to America began in earnest more than a hundred years earlier, but the Famine years, from 1846 to 1851, were marked by an urgency to get away as never seen before. Ships had always sailed in the spring and summer months. Now, the clamour for a passage saw vessels of every kind and size, with bunks hastily raised in the holds, departing in the autumn and winter too. They braved the worst of the weather the bitter cold, ice, gales, fog, storms and heavy seas, short days and long nights, could not deter these desperate people. Desperation was the distinctive feature of the Famine sailings.

As the potato crop was wiped out in successive years, Ireland started to starve and the exodus to America began. On tiny two- and three-masted ships they sailed from Dublin and Donegal, from Sligo, Galway and Limerick, from Waterford and Wexford, New Ross, Belfast, Londonderry and Cork, from Tralee, Drogheda, Newry, Kilrush, Westport and Youghal, directly to America.