The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

It is marvelous enough that man is capable at all to reach such a degree of certainty and purity in pure thinking as the Greeks showed us for the first time to be possible in geometry.

THE SUPERINTENDENTS CRIME

The sun was setting in the summer sky of August 17, 1661, when the young king of France descended from his gilded carriage onto the front steps of the chteau of Vaux-le-Vicomte. Only a few years in the making, and still under construction, the chteau was the pride and glory of its owner, Nicolas Fouquet, the kings superintendent of finances. At Vaux, he had built his dream house and garden, a magical land of canals and fountains, woods and fruit groves, open vistas and hidden springs. Sparing no expense in his preparation for the royal visit, Fouquet was determined to dazzle his guest with a celebration worthy of a king.

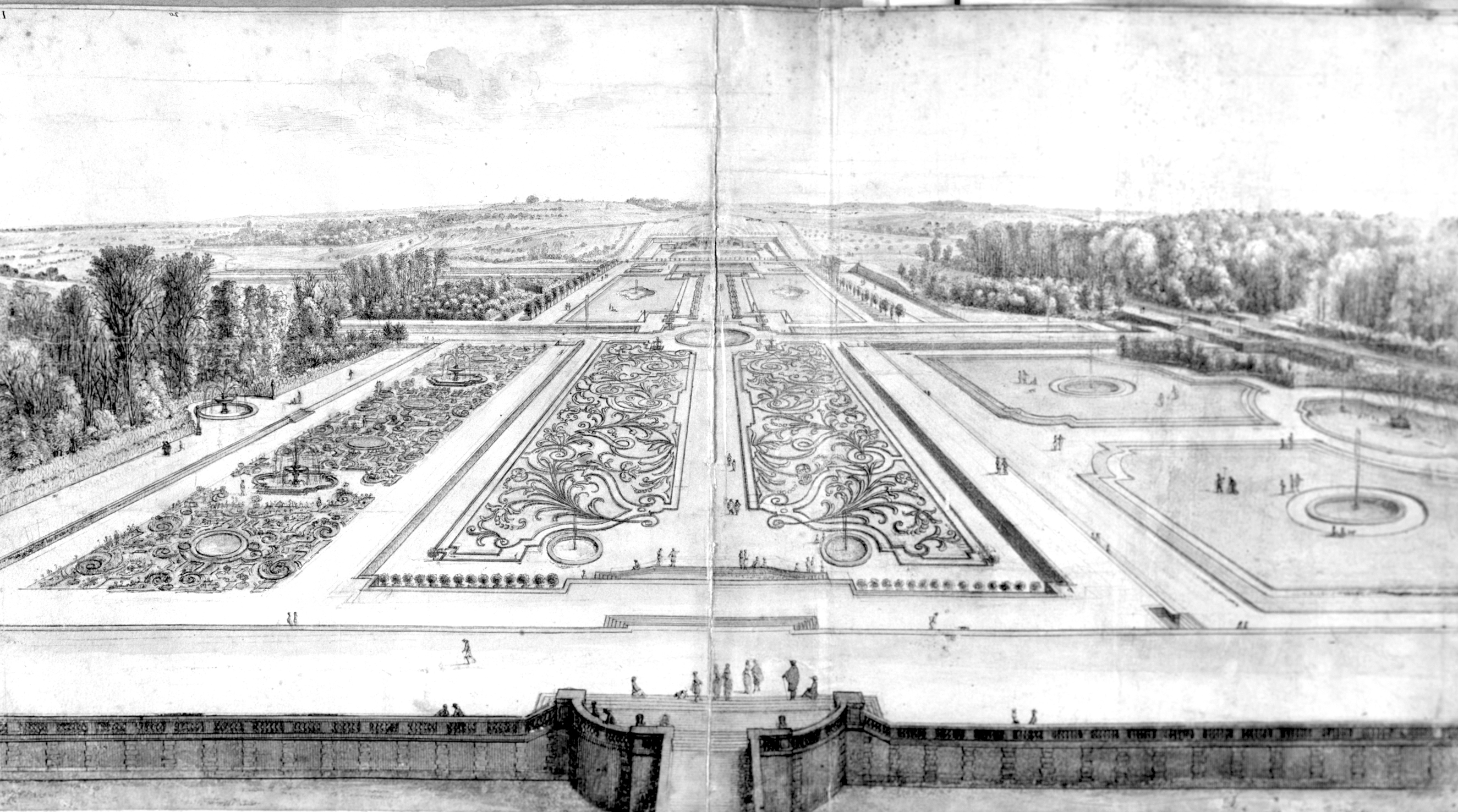

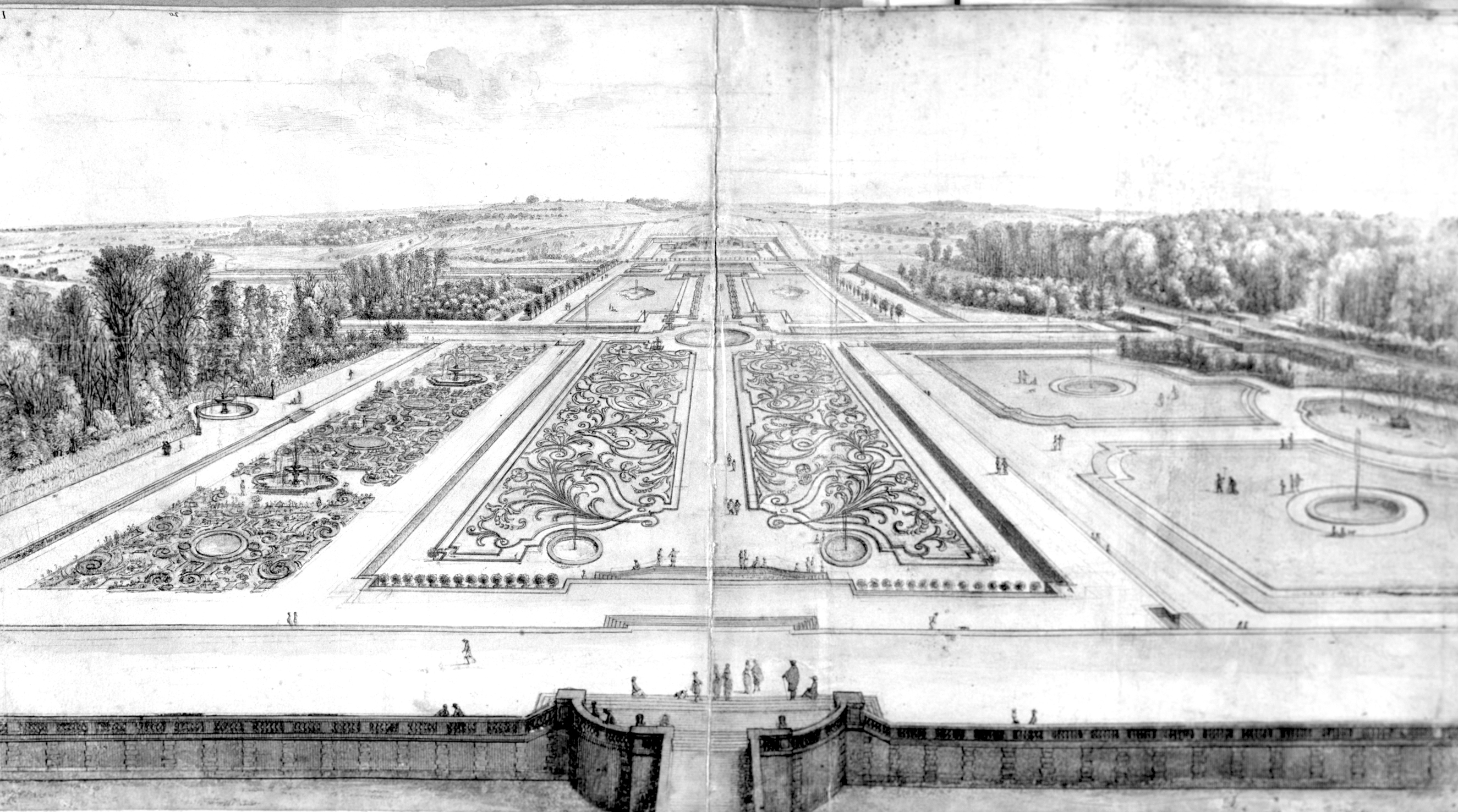

Fouquet first led the king and his retinue on a tour of the elegant new chteau, designed by his favorite architect, Louis Le Vau. He guided them through the main hallway, decorated by Frances leading painter, Charles Le Brun, then showed them on to the gardens behind it, created by the inimitable Andr Le Ntre. There, they walked through the broad central avenue that stretched southward from the center of the chteau to the gardens farthest end, dividing it into two near-identical halves. They passed between rectangular parterres, known as the Embroidery for their exquisitely-gardened patterns, and gazed into the placid water circle between the two straight branches of the central canal, leading east and west. Proceeding between the symmetrical pools of Triton they paused to meditate before the great square mirror of water and finally settled down in front of a semicircular grotto. There they were treated to a performance of The Bores, a new comedy-ballet Molire had written for the occasion. A sumptuous meal served to each member of the royal court and the five thousand household guards was followed by a display of fireworks. They shot up from the chteaus central dome and lit up the sky, then slowly descended on the gardens like midnight suns.

FIGURE 1: The gardens of Vaux-le-Vicomte today, pen and ink and watercolor by Israel Silvestre the Younger (16211691)

The next morning Fouquet saw off the king and his retinue, still basking in the glow of royal approval. But as the king settled himself in the royal carriage on his way to the royal castle of Fontainebleau, he turned to his aging mother and remarked with disdain: Ah, Madame, should we not make these people disgorge all of that?

Louis XIV was only twenty-three years old at the time, but already a man of his word. Three weeks after the festivities at Vaux he invited Fouquet to join him on a royal trip to Nantes, and there he set his trap. While showing every sign of favor in an audience with the superintendent, he secretly summoned the Comte dArtagnan, captain of the Kings Musketeers, to the adjacent room. DArtagnan, the historical inspiration for Alexandre Dumass famous hero, had known Fouquet for years and had benefited from his largesse, but he did not hesitate. At a sign from the king the dashing musketeer sprang forward and placed his former friend under arrest.

Soon after, Fouquet was put on trial for despoiling the royal treasury. His personal popularity and friends in high places helped sway the judges sufficiently to spare his life and sentence him to permanent exile. But the king would not be denied: by royal decree he commuted Fouquets sentence from exile to life imprisonment and kept him locked up in an alpine fortress for the remainder of his days. He died a forgotten man in 1680, without ever setting eyes on his beloved estate again.

How had the loyal Fouquet, who had known Louis since childhood, incurred the kings wrath? Partly, no doubt, it was his success that made him a marked man. Fabulously wealthy, the owner of a private fleet of armed merchant vessels, and master of the strategic island of Belle-Isle, Fouquet was an obvious target for a young king looking to assert his authority. But power politics alone cannot explain Louiss vengefulness. After all, the king had been lenient with the leaders of the Frondean uprising that marred the early years of his reignand he forgave the wealthy grandees of the Parlement of Paris for their key role in it; he tolerated the questionable loyalty of the provincial nobility, choosing to draw them to his court rather than bring them to heel; and he entirely forgave his ablest general, the Grand Cond, who had gone so far as to take up arms against his sovereign. But for Fouquet there was no mercy. Though he professed nothing but love and loyalty to his king, he was condemned by his implacable monarch to a cold and lonely prison cell from the day of his arrest to his death nineteen years laterlong after he could possibly have been considered a threat.

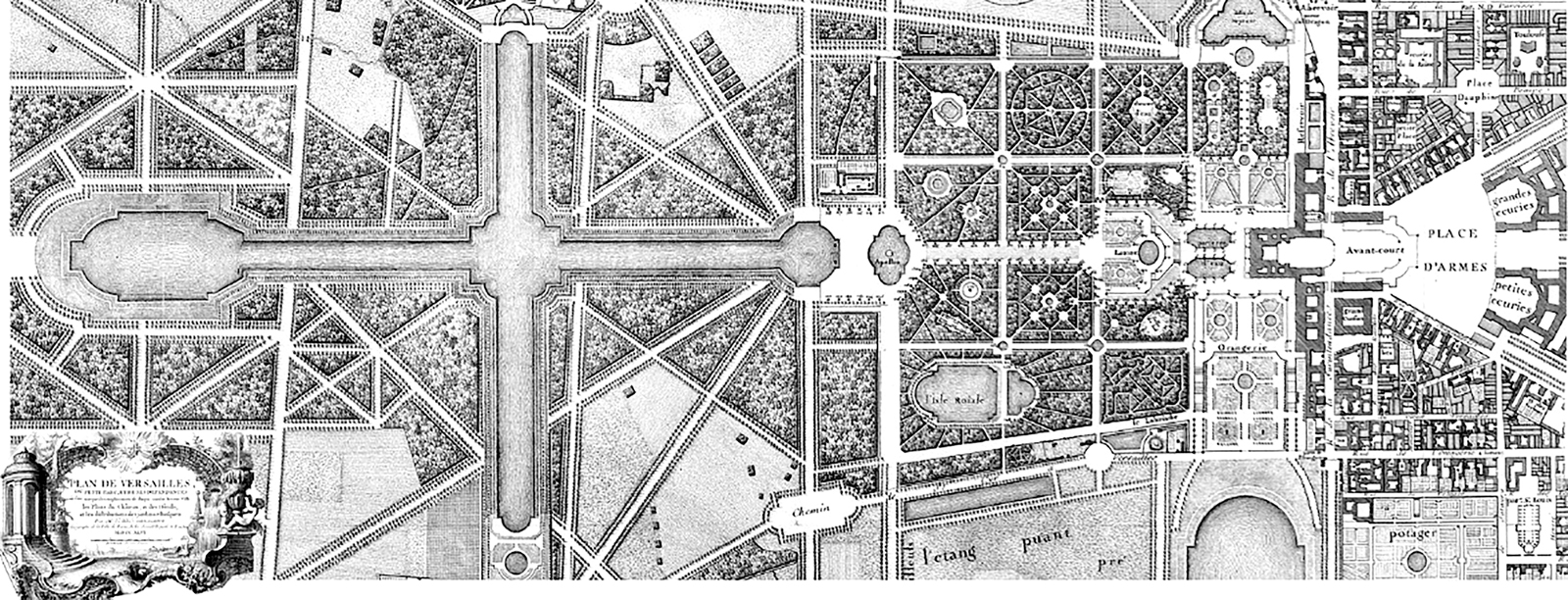

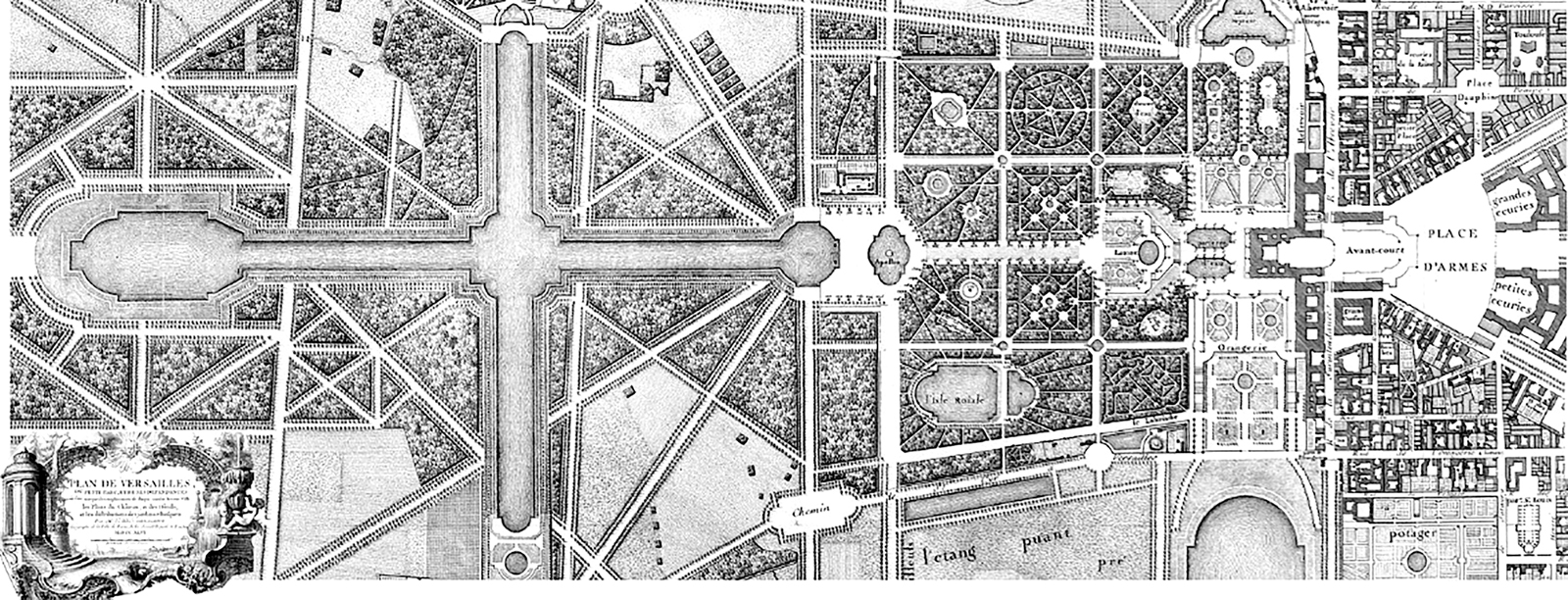

FIGURE 2: Abbot Delagrive, ground plan of the gardens of Versailles, 1746

Fouquets offense was clearly unforgivable, but what exactly was it? To understand this we must return to the scene of his crime, the beautiful chteau of Vaux-le-Vicomte. Shortly after Fouquets arrest an army of looters descended on the grounds like a swarm of locusts. In the gardens they uprooted trees, shrubs, and flower beds, pulled out ancient statues and bubbling fountains. From the chteau they took paintings, sculptures, and gilded chandeliers. But the raiders were not brigands from the countryside: they were the kings men, sent to take down all the objects that had made Vaux the enchanting palace that it was. They carefully packed the objects into crates and hauled them away to a marshy town where Louis was intent on building his own dream palace. It was called Versailles.

Nor were fountains and sculptures the only things Louis transported from Vaux to Versailles; he brought the people as well. With Fouquet safely out of the way, the king immediately enlisted Le Vau to design his new palace. Charles Le Brun, the painter who had decorated the interiors of Vaux, now had the same job in Versailles, and the literati who had lent brilliance to Fouquets court were packed off to Versailles to perform the same duties for the king. But Louiss greatest acquisition from his fallen courtier was not a writer, a painter, or even an architect. It was the gardener, Andr Le Ntre. The king appointed him Chief Architect of the gardens of Versailles, and immediately set him to work recreating Fouquets gardens on an immensely grander scale.

IT WAS AT VERSAILLES THAT the true nature of the superintendents crime was revealed. It was not the superintendent himself who had provoked Louiss wrath, for Fouquet could perhaps have been forgiven: it was, rather, his sparkling geometrical estate that the king could not tolerate. It was Vaux-le-Vicomte that had become the kings obsession and drove him not only to despoil it but to co-opt it, and to do so on a scale that would dwarf the original and erase it from memory. And so, in the end, it was not Fouquets wealth, or his private fleet, or his hasty decision to fortify his island of Belle-Isle that did him in; it was his geometrical garden.