Contents

Page List

Guide

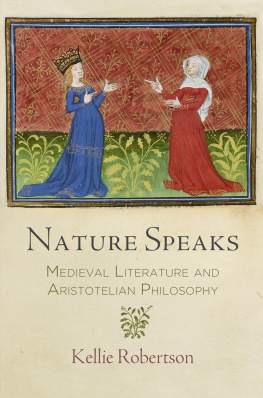

Nature Speaks

THE MIDDLE AGES SERIES

Ruth Mazo Karras, Series Editor

Edward Peters, Founding Editor

A complete list of books in the series is available from the publisher.

NATURE SPEAKS

MEDIEVAL LITERATURE

AND ARISTOTELIAN PHILOSOPHY

KELLIE ROBERTSON

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA PRESS

PHILADELPHIA

Copyright 2017 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

A Cataloging-in-Publication record is available from the Library of Congress

ISBN 978-0-8122-4865-4

Omne quod movetur ab alio movetur.

For Mike and Silas,

first and finest movers

CONTENTS

A NOTE ON CITATIONS AND ABBREVIATIONS

References to Aristotles works are by book and chapter followed by Bekker number, for example, Physics 2.1 (193a32193b6). English citations refer to The Complete Works of Aristotle: The Revised Oxford Translation, ed. Jonathan Barnes, 2 vols. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984).

The Latin text of Thomas Aquinass Summa theologiae follows the Leonine version: Opera omnia, ed. Leonine Commission (Rome: Commissio Leonina, 1882); its English translation is that undertaken by the Fathers of the English Dominican Province. It is cited by part, question, and article, for example, ST 1a.28.2 (1a = first part; 1a2ae = first part of second part; and so on). Quotations from the Bible follow the Douay Version.

I have used Flix Lecoys edition of the Roman de la Rose, 3 vols. (Paris: Champion, 196570), and cite the English translation of Charles Dahlberg (The Romance of the Rose [Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1971]) with occasional silent emendations. All references to Chaucers works are taken from The Riverside Chaucer (ed. Larry D. Benson, 3rd ed. [Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1987]). All unattributed translations are my own.

CUP | Chartularium Universitatis Parisiensis, ed. Heinrich Denifle and mile Chatelain, 4 vols. Paris: Fratrum Delalain, 188997 |

DMF | Dictionnaire du Moyen Franais (13301500) |

EETS ES | Early English Text Society, Extra Series |

EETS OS | Early English Text Society, Original Series |

Image | LImage du monde de Matre Gossouin: Rdaction en prose; Texte du manuscrit de la Bibliothque Nationale, Fonds Franais No. 574, ed. O. H. Prior. Paris: Payot, 1913 |

MED | Middle English Dictionary |

OED | Oxford English Dictionary |

PJC | Guillaume de Deguileville, Le plerinage Jhesucrist, ed. J. J. Strzinger. Roxburghe Club 133. London: Nichols, 1897 |

PVH | Guillaume de Deguileville, Le plerinage de vie humaine, ed. J. J. Strzinger. Roxburghe Club 124. London: Nichols, 1893 |

ST | Thomas Aquinas, Summa theologiae |

STC | A. W. Pollard and G. R. Redgrave, A Short-Title Catalogue of Books Printed in England, Scotland, and Ireland 14751640, 2nd ed., rev. and enlarged by W. A. Jackson, F. S. Ferguson, and Katharine F. Pantzer. 3 vols. London: Bibliographical Society, 198691 |

INTRODUCTION

Medieval Poetry and Natural Philosophy

This book brings together two subjects that are generally kept apart, both in popular thought and by academic disciplines: love and physics. They are usually imagined as non-overlapping magisteria, to repurpose a phrase coined by the evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould. Each occupies its own sphere and is assumed to obey different laws. Love concerns the human; physics the nonhuman, from subatomic particles to the motions of the universe. This distinction rests on an even deeper assumption about the division between, on the one hand, the ineffable flux of conscious inner life and, on the other, a world of material objects existing somewhere out there. Theoretical segregation is reinforced on the level of praxis, since research and expertise in these fields are certified by a far-flung group of professionals: physicists, astronomers, and topological mathematicians as opposed to fiction writers, psychologists, and the operators of online dating services.

Yet for medieval writers, both popular and academic, these domains not only overlapped, but they were also thought to operate according to the same principles. Nature Speaks argues that for a significant group of writers popular in late medieval EnglandGeoffrey Chaucer being only the most well-known todaynatural philosophy and the academic controversies it generated were not just a source of learned allusion but also the most obvious place to look when trying, as writers must, to transform the world into words. Unlike todays largely mathematical discipline, medieval natural philosophywhat we call physicswas primarily a textual endeavor; like medieval poetry, it was a set of interpretive practices that sought to divide up the material world, making it more amenable to human view. Medieval poets and natural philosophers thus shared a vocabulary and, more important, an orienting set of questions about the moral authority of the natural world and the writers ability to claim this authority when representing his or her own experience.

The medieval category of Aristotelian philosophy was a vast one that encompassed not just ethics, politics, and religion but also physics, chemistry, and psychology along with the foundational arts of rhetoric, logic, and grammar. This book focuses on just one part of this heterogeneous body of learning: academic debates over what in Middle English was often called simply philosophiea term that, as I argue below, frequently denoted natural rather than moral philosophy. I trace how a certain strain of vernacular literary production responded to the shifting fortunes of Aristotles scientific writings, writings that formed the core of the arts curriculum from the thirteenth century forward. While these writings were central to university education, parts of these texts were viewed with suspicion and were repeatedly condemned by ecclesiastical authorities who discouraged discussion of their potentially controversial contents. Such censure did not prevent either clerics or poets from arguing over natures proper authority in popular writings. By showing philosophys reach, this book offers a corrective to the critical tendency to treat a recognizably courtly poet such as Chaucer in isolation from that other Chaucer, well known to his early readers as the author of the