CONTENTS

DIVISION LECLERC

THE LECLERC COLUMN & FREE FRENCH 2nd ARMORED DIVISION, 19401946

INTRODUCTION

The Allied defeat in the Battle of France in MayJune 1940 culminated with the German entry into undefended Paris on June 14. On June 17 a radio broadcast announced that a new regime headed by the 84-year-old Marshal Philippe Ptain had replaced the government of Premier Paul Reynaud, and would seek an armistice with Germany. The following day, far fewer Frenchmen heard a BBC broadcast from London by the French junior defense minister, BrigGen Charles de Gaulle, rejecting any armistice and calling on Frenchmen everywhere to continue the fight alongside Great Britain.

The Armistice announced on June 22, and endorsed overwhelmingly by a vote of parliamentary suicide on July 10, ceded the whole of northern and western France to German occupation, while the authoritarian Ptain regime, based in the city of Vichy, would govern a new French State in unoccupied central and southern France. It would retain a 100,000-man Armistice Army, plus more than twice that many colonial garrison troops in Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria, the Levant, Frances colonies in West and Equatorial Africa, and in the Far East.

Reeling from the national disaster, and lacking any political alternative, a large proportion of the French public took hope from the paternalistic appeal of the admired Great War hero Ptain. The Armys officer corps, also shocked and disoriented by defeat and the collapse of the Third Republic, faced painful choices. While the Occupation was bitter, it could be argued that legally they owed obedience to Ptains defacto government; their priority was to preserve what was left of the Army and the national territory, and to guard the French Empire which the Armistice had left them. In 1940 very few proved willing to risk everything by joining De Gaulles handful of refugees in beleaguered Britain, which itself faced the threat of German invasion. Nevertheless, from the moment De Gaulle made his intentions clear on June 18, a small group of soldiers, sailors and airmen resolved to follow him. Completely reliant on British resources and goodwill (both of which were more theoretical than practical at this moment of crisis), De Gaulle formed a government-in-exile, complete with tiny embryo armed forces designated the Forces Franaises Libres (Free French Forces FFL), which took as their emblem the Cross of Lorraine.

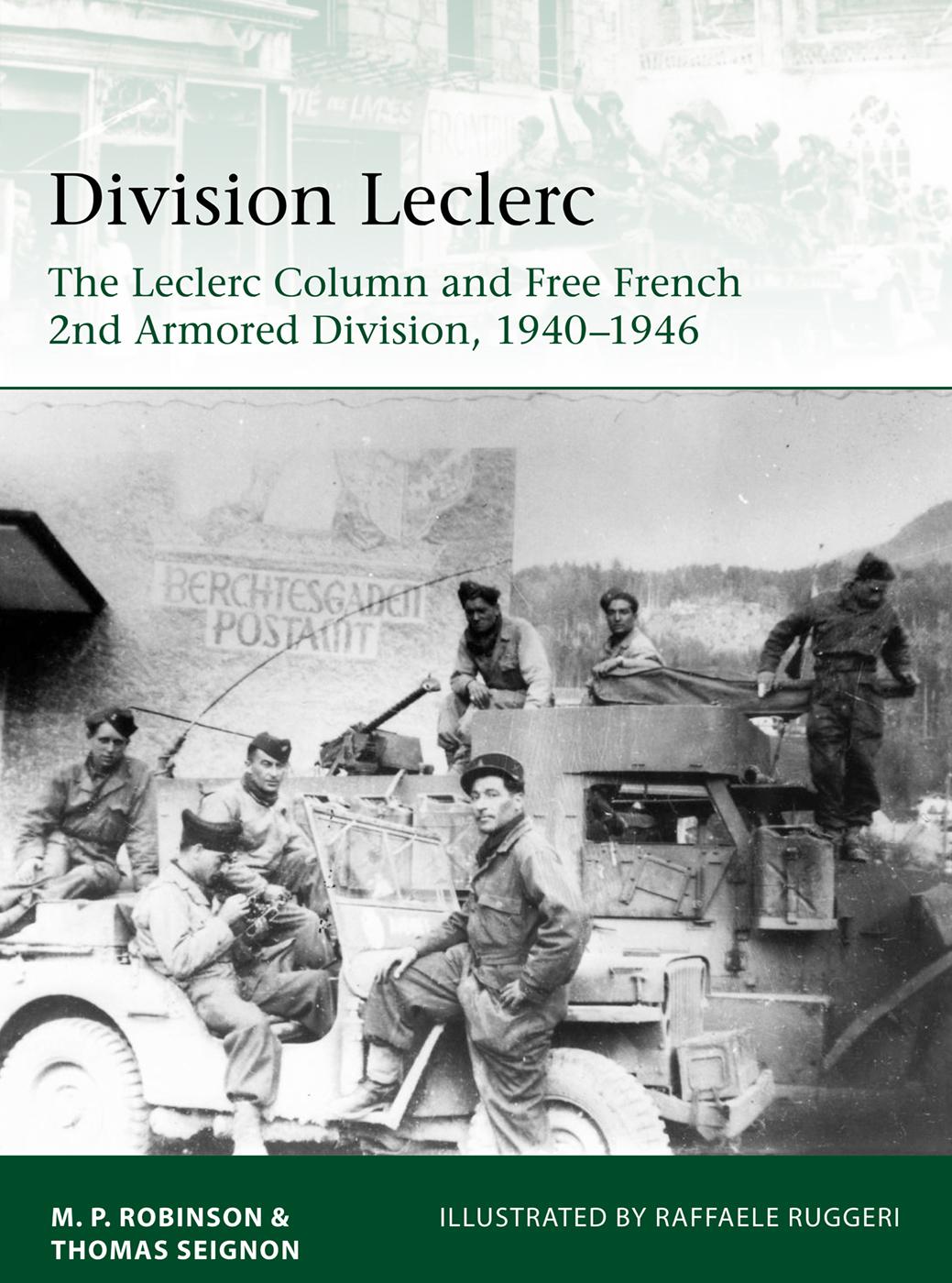

Captain Philippe de Hauteclocque (center), seen among fellow staff officers of the 4me Division dInfanterie during the Phoney War of winter 19391940. De Hauteclocque managed to escape the encirclement of the division around Lille during the night of June 4/5, 1940, but was wounded on June 14 while fighting with the 3me Division Lgre Mecanise in the Aube region. When German troops entered his hospital, he escaped through a window and stole a bicycle. After warning his family of his intentions, he made his way first to Spain and then to Portugal, using false ID in the name of Franois Leclerc. Via the port of Lisbon, he managed to join De Gaulles Free French Forces in London on July 25, 1940.

Captain Philippe de Hauteclocque was among the first officers to join the FFL in Britain, despite his background in the solidly conservative, nostalgically monarchist, devoutly Catholic caste most likely to find Ptains appeal attractive. The son of a papal count, from a line of chevaliers that had served France since the Middle Ages, De Hauteclocque was born at Belloy-St-Leonard in Picardy on November 22, 1902. He had witnessed the Great War as a teenager, had lost two uncles in 1914, and had always expected to serve his country as a cavalry officer. He entered St-Cyr in 1922 and graduated from the Saumur cavalry school in 1925. De Hauteclocque served first in the 5me Rgiment de Cuirassiers in the French-occupied Sarre region of the Rhineland, before transferring to the 8me Spahis in Morocco, where he saw active service leading irregular goumiers in the aftermath of the Rif War. He was decorated for valor in close combat in the Atlas Mountains during a second Moroccan tour in the 1930s. By 1940 the 38-year-old Capt de Hauteclocque was a trained staff officer, whose valuable experience of colonial warfare at the end of long supply lines had taught him to plan thoroughly, but always to be ready to improvise.

By spring 1945, having officially changed his name to Leclerc de Hautcloque, the commander of the 2me Division Blinde was the second most famous man in France, after Charles de Gaulle. At the age of only 43, in just over four years he had been promoted from captain to four-star general. As a passionately determined patriot, his absolute loyalty to Gen de Gaulle and his impatience with politics had led to quarrels both with ex-Vichy generals resentful of his meteoric promotion and unique esteem, and with senior US officers angered by episodes of disobedience. However, he enjoyed the respect of both Montgomery and Patton not something that many men could claim. While he was a dashing and hard-driving commander, and subject to occasional bursts of fury (as when confronted by French prisoners from a Waffen-SS unit), he was a devout man who lived with great personal simplicity, and he earned warm loyalty among his officers and men.

Nom de guerre: from Captain de Hautcloque to Major Leclerc

For his escape to England, De Hauteclocque chose the inconspicuous name Leclerc. Taking on a false identity was a widespread practice among these Gaullists of the first hour, whose decision exposed their families to reprisals (having married young, De Hautecloque left behind a wife and no fewer than six children.) He could only hope that he would be counted by the authorities among the missing or presumed dead.

The Franco-British relationship underwent great strains in the wake of Frances defeat, especially after the Royal Navys attack on the Vichy French fleet at Mers-el-Kebir in July 1940 and the seizure of French warships in Allied ports. The number of French soldiers available to De Gaulle was at first negligible. Most of the 122,000 evacuated from Dunkirk had returned to France before the Armistice and were now in German captivity. Perhaps 2,000, more than half of them Foreign Legion returned from the Norwegian campaign, were still in Britain, but apart from individual officers few recruits for the FFL were forthcoming from Metropolitan France. De Gaulle therefore turned his eyes towards the substantial French forces in Africa; could they be persuaded to fight on?

Leclercs personal qualities and colonial experience had clearly impressed the general, who immediately promoted him to major, and gave him a mission appropriate to a much higher rank. With a couple of dozen others, he was ordered to make his way to Africa and rally Frances Equatorial African colonies to the banner of the FFL. Within ten days Leclerc was aboard an RAF Short Clyde flying boat on his way to Nigeria.

CHRONOLOGY

La Colonne Leclerc, 194043: