1 Crunch, Bang, Ouch!

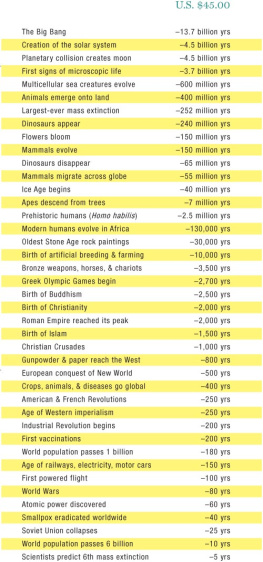

How an invisible speck of infinite energy exploded our universe into existence, with its galaxies of stars and constant laws of physics.

TAKE A GOOD look around. Put everything you can see inside an imaginary but enormously powerful crushing machine. Plants, animals, trees, buildings, your entire house (including contents), your home town as well as the country where you live. See it all get pulverized into a tiny ball.

Now put the rest of the world in there, too. Add the other planets in our solar system and the sun, which is about 1,000 times bigger than all the planets put together. Then put in our galaxy, the Milky Way, which includes about 200 billion other suns, and finally all the other galaxies in the universe, many of which are bigger than ours there are about another 125 billion of these. See all this stuff squeezed together, reduced to the size of a brick, then a tennis ball, now a pea finally, see it crushed even smaller than the dot on top of this letter i.

Then it disappears. All those stars, moons and planets vanish into a single, invisible spec of nothing. That was it the universe began as an invisible dot, a 'singularity', as scientists like to call it.

This invisible, heavy and very dense dot was so hot and under such enormous pressure from all the energy trapped inside it that about 13.7 billion years ago something monumental happened.

It burst.

This was no ordinary explosion. It was an almighty explosion, the biggest of all time it was what we now call the Big Bang. What happened next is even more dazzling. It didn't just make a bit And there's also a whole lot more that we can't see yet, because our telescopes can't peer that far. In fact, the universe is so big that no one really knows how wide or deep it actually is.

Why do experts think such an incredible event took place, especially when apparently it happened so long ago, and no one was there to witness it? Many people to this day are understandably suspicious of the whole Big Bang idea. But scientists are in broad agreement about what happened, because, they say, the evidence is all around us.

Frenchman Georges Lematre was so shocked by the slaughter he witnessed on the battlefields of the First World War that he devoted most of his life to studying the stars. He first became interested in space in 1923, during a trip to Cambridge University, where there was an observatory that contained some of the biggest telescopes in the world. By 1927 he had become recognized as a great mathematician, and he developed a new theory of an expanding universe which all started with a very big bang.

Just two years after Lematre published his ideas, another scientist called Edwin Hubble claimed that through a powerful telescope he could see other galaxies moving away from the earth, and that the further away they were, the faster they were moving. Here was visible evidence that the universe was still expanding. Hubble reasoned that a long time ago, something must have forced the stars and galaxies outwards something like Lematre's Big Bang.

Echoes from thunderstorms can bounce around mountains and valleys for a long time, sometimes more than a minute. The Big Bang was such an enormous explosion that scientists reckoned it should still be possible to detect its echo.

It was first picked up in 1964 by two American engineers in New Jersey: Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson. At the time they were trying to find ways to improve the design of radio telescopes. But their new telescope kept picking up a mysterious noise. Regardless of which direction they pointed it, the irritating interference would not go away. The two engineers went off to investigate a nearby radio transmitter in New York City, thinking it could be the source of the trouble. When they found it was full of pigeons, they thought what they were hearing was perhaps the sound of the birds being amplified by the radio mast. The pigeons were removed, the transmitter was cleaned up, but still the mysterious noise remained.

Just thirty miles away another team of scientists, led by cosmologist Robert Dickie, was trying to perfect a highly sensitive space microphone which they hoped could detect the echo of the Big Bang. By chance, Penzias and Wilson telephoned Dickie to see if he, or anyone in his team, had any ideas on how they could get rid of the background noise on their new telescope. Almost immediately Dickie suspected that what Penzias and Wilson were hearing might be the echo of the Big Bang. Today you needn't just take their word for it. Think of those fuzzy black and white dots that appear on a television screen when it isn't tuned properly. One in every hundred of those dots is caused by the background echo of the Big Bang.

Even if we accept the idea that an invisible speck exploded our universe into existence, why do scientists believe it happened 13.7 billion years ago? Using modern telescopes, scientists have been able to build on Hubble's observations and calculate the actual speed at which galaxies are spreading outwards. With this data they can project backwards in time to work out how long ago these objects were all together in one place.

Just after the Big Bang, more mysterious things started to happen. An enormous blast of energy was released. First it was transformed into the force of gravity, a kind of invisible glue that makes everything in the universe want to stick together. Then the massive surge of energy created countless billions of tiny building bricks like microscopic pieces of Lego. Everything that exists today is made of billions of particles that originated a fraction of a second after the Big Bang.

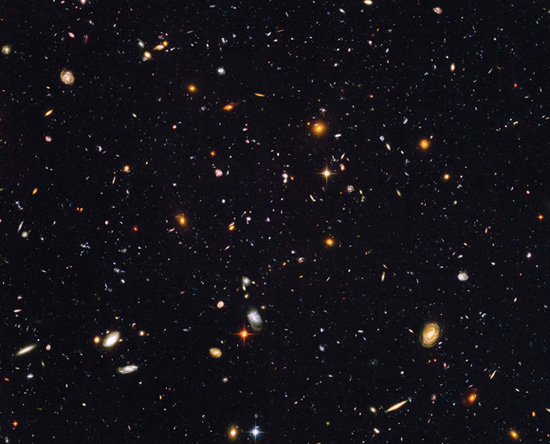

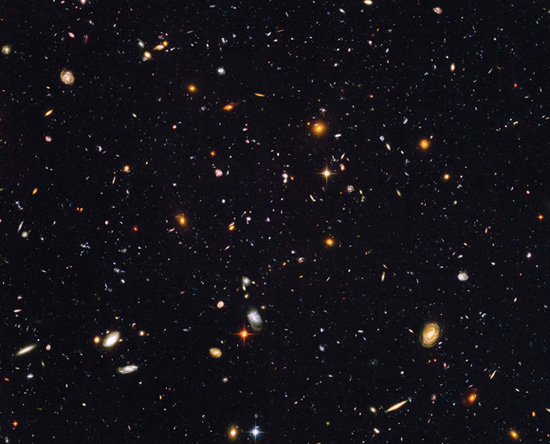

The deepest ever view of the universe pictured by the Hubble space telescope in 2004. Each dot of light is a separate galaxy, some dating back more than 13 billion years.

About 300,000 years later things had cooled down enough so that these particles the most common of which are electrons, protons and neutrons could start to stick together into tiny blobs which we call atoms. With the help of that glue gravity and the passing of a little time, these atoms gathered together to make enormous clouds of very hot dust. Out of these clouds came the first stars, massive balls of hot fire supercharged with energy left over from the Big Bang. Gravity made the fiery stars gather into groups of many different shapes and sizes some in spinning spirals, some in the shape of spinning plates. We call these clusters of stars galaxies. Our galaxy, the Milky Way, was formed about 100 million years after the Big Bang that's 13.6 billion years ago. It's in the shape of a large disk like two back-to-back fried eggs that spins round at a dizzying speed of about 500,000 miles per hour.

New information about the origins of our universe was gathered by an American spaceship called the Wilkinson Probe, launched in 2001. This has enabled scientists to make the most accurate measurements yet of the Big Bang's echo and of everything else that makes up the universe. The probe also confirmed that, as Hubble saw through his telescope, the universe is still expanding. But many mysteries remain.

For instance, no one knows whether the universe's expansion is slowing down or not. If it is slowing, then perhaps gravity will one day start to pull all the stars and galaxies backwards again as if they are on an immense, invisible elastic band. This means that the universe might one day get squashed back into a tiny invisible speck, and as the pressure inside the speck builds, that could lead to another Big Bang. Some scientists even believe that there may have been millions of previous Big Bangs, and that our current universe is just the latest in line before it gets crunched up and a new one takes its place.