KILLING FOR THE REPUBLIC

Killing for the Republic

CITIZEN-SOLDIERS AND THE ROMAN WAY OF WAR

Steele Brand

2019 Johns Hopkins University Press

All rights reserved. Published 2019

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1

Johns Hopkins University Press

2715 North Charles Street

Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363

www.press.jhu.edu

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Brand, Steele, author.

Title: Killing for the republic : citizen-soldiers and the Roman way of war / Steele Brand.

Description: Baltimore : Johns Hopkins University Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018048626 | ISBN 9781421429861 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 1421429861 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781421429878 (electronic) | ISBN 142142987X (electronic)

Subjects: LCSH: RomeArmy. | RomeHistory, Military. | Military art and scienceRome.

Classification: LCC U35 .B69 2019 | DDC 355.00937dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018048626

A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

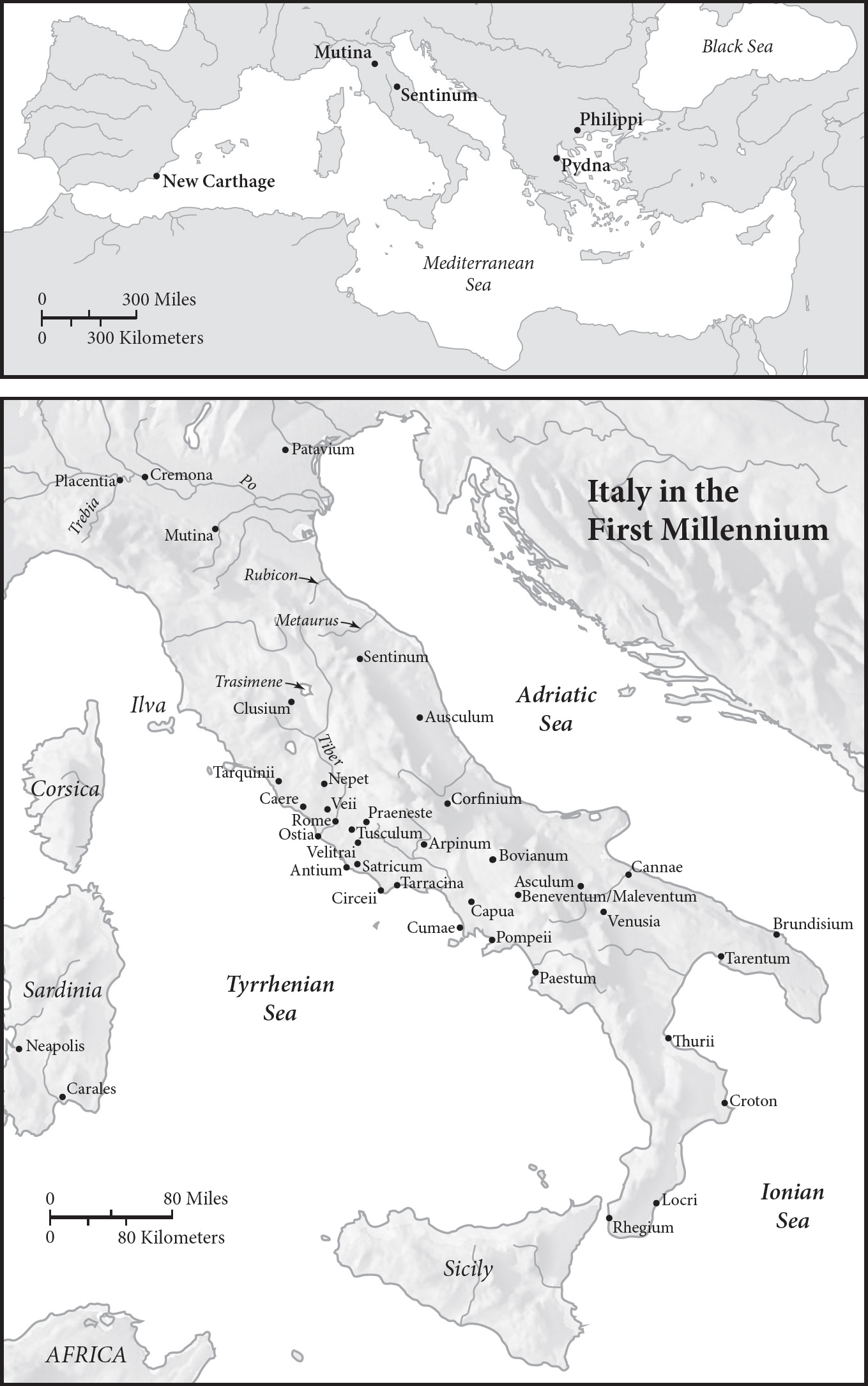

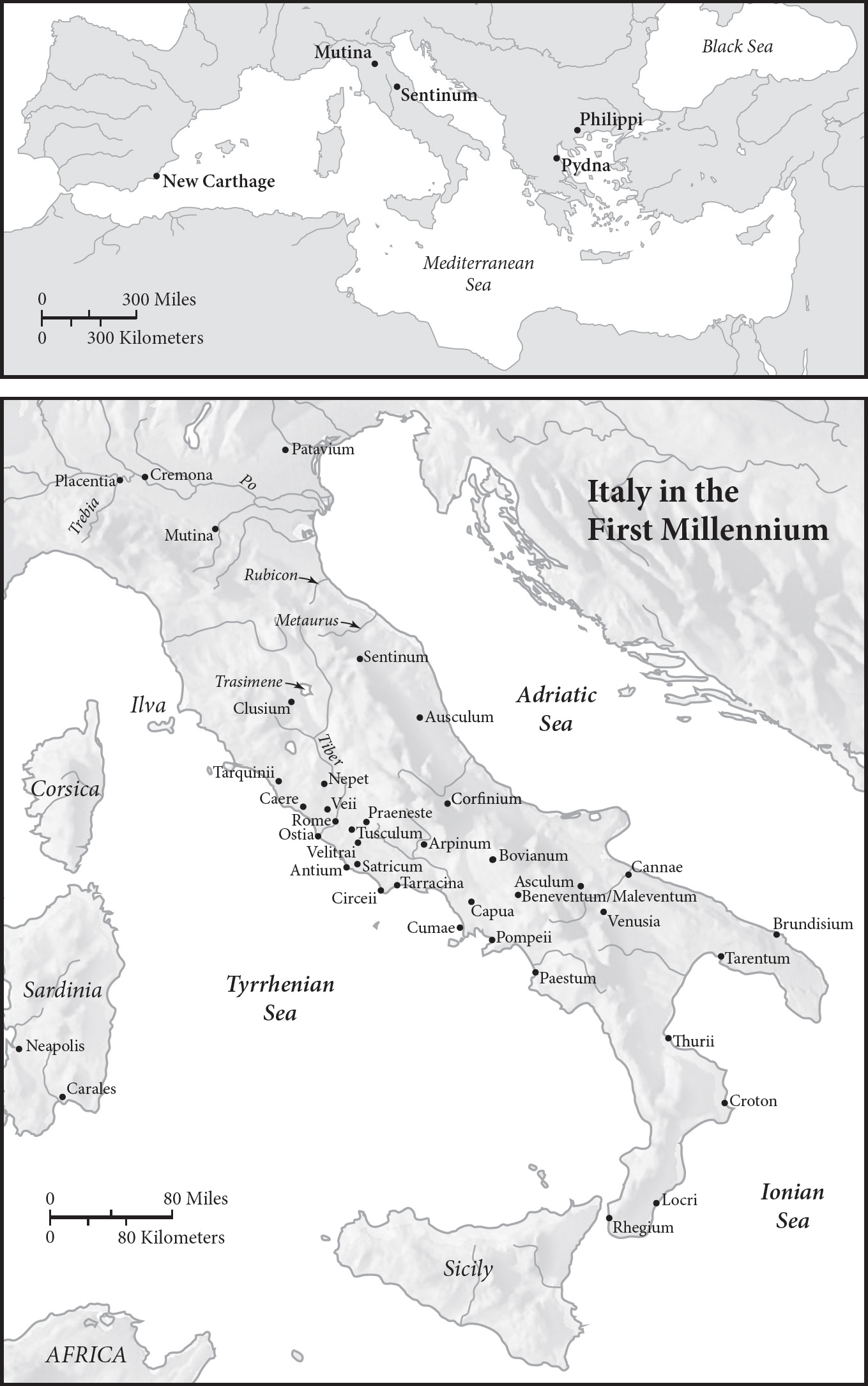

Maps and diagrams courtesy of Lucidity Information Design, LLC.

Special discounts are available for bulk purchases of this book. For more information, please contact Special Sales at 410-516-6936 or .

Johns Hopkins University Press uses environmentally friendly book materials, including recycled text paper that is composed of at least 30 percent post-consumer waste, whenever possible.

To Will, for giving it a chance

To Matt, for believing in it

To Megan, for putting up with it

PREFACE

Why Care about Long-Dead Fighting Farmers?

In 146 BC, armies of the Roman Republic concluded their 118-year struggle for the western Mediterranean when they breached the walls of their inveterate foe Carthage. Roman troops slaughtered many of the citizens in brutal street fighting, enslaved those that remained, and leveled the city. The Roman commander Scipio Aemilianus watched Carthage as it was being destroyed and pondered its seven-hundred-year existence. Overcome with the magnitude of the moment, he wept. Scipio then turned to his friend, the historian Polybius, and remarked, A glorious moment, Polybius; but I have a dread foreboding that some day the same doom will be pronounced on my own country (Polybius, 38.21; Appian, Punica, 132). Later that year across the Mediterranean near Corinth, another Roman army defeated the Achaean League. In the preceding half a century, Rome had repeatedly humiliated Alexanders successor kingdoms in Macedonia and Syria, and this battle terminated what freedom remained for those Greek states caught in the middle. When the Romans entered Corinth, they enslaved its population and plundered its treasures. Uncouth soldiers supposedly played games atop famous works of art (Polybius, 39.2). In this fateful year, Rome became the master of the Mediterranean world. Even more remarkable was that they had done so with citizen-soldiers. How did such a thing happen? What had made Rome so powerful? And, if Scipio was right about the rise and fall of republics, does this have any meaning today?

This book answers these questions by describing how Roman farmers were transformed into ambitious killers. Like many expansionist states throughout history, Rome instilled something violent and vicious in its soldiers, making them more effective than their opponents. But unlike the Assyrians, Persians, Macedonians, and other imperial peoples of history, the Romans did so with part-timers. They perfected civic militarism in a way no other civilization ever has.

The Roman Republic was born in a chaotic world where competing city-states, kingdoms, and empires sought to dominate or annihilate their neighbors. By the end of the fourth century BC it had outstripped its neighboring Italian city-states and leagues by creating the best constitution with the deadliest citizen-soldiers. In the third century, Rome defeated the multitalented mercenaries of monarchic adventurers like Pyrrhus and commercial republics like Carthage. In the second century, Rome looked east and distinguished itself from the Hellenistic kingdoms that flourished in the wake of Alexanders death. In the Roman mind these monarchies had done away with the republicanism of city-states such as Athens and Sparta, and the Macedonian war machine now threatened liberty and justice in the West. Rome shocked the Mediterranean world by defeating the heirs of Alexander one by one and then taking over their domains. This is the story of how they did it and why it still matters.

Romes capacity for winning wars in this struggle to survive is well known, but the legacy of how it won its wars through republican virtues is disappearing. Today, intellectuals often describe the Roman Republic as an undemocratic, militaristic precursor to the more important empire that would follow. Postmodernists decry the colonialism, imperialism, and patriarchy of ancient Rome. And younger generations often sympathize with the titanic personalities that orchestrated the republics collapse; characters like Pompey, Caesar, and Antony are often seen as victims of their circumstances who were just trying to get ahead in an amoral world. Each of these critiques has a point, but they undervalue the circumstances of Romes uniqueness as the finest ancient republic. They also miss the singular genius of Romes republican spirit, which earned it the right to dominate the Mediterranean in the last centuries before Christ. This same spirit eventually inspired the rebirth of republicanism for future generations in places like Florence, Venice, Britain, and the United States.

With the limited sources remaining, we do not know all the qualities of Romes neighbors, but we do know what ancient authors said made Rome distinctive. Historians like Polybius, Livy, and Dionysius argue that the Romans created the best republican system in the most capable federation of the ancient world. Roman political ingenuity was matched by capable military institutions, which marshaled vast numbers of men, absorbed defeats in the field, adapted technologies from neighbors, and allowed the best commanders and troops to achieve victory in the long run. Yet Roman institutions were imperfect and would have achieved little had they not rested on a resilient culture that inculcated civic virtues like honor, piety, loyalty to patrons and family, hard work, and the rugged independence inherent in smallholding farmers. Rome survived by unifying disparate political elements under constitutional orders that relied on average citizens with agricultural lifestyles. Farming may have been ubiquitous in the ancient world but politically empowered farmer-citizens were not, and militarily proficient farmer-citizen-soldiers were rarer still. These citizens took ownership of their republic to such lengths that they heartily sacrificed themselves and their enemies on the altar of republican glory. This was the Roman way of war.

The history of Romes citizen-soldiers has implications for the United States in the twenty-first century. Rome was maintained by different values and defended by different strengths than modern republics. The Roman republican embodied physical interaction with the soil, resistance to tyranny, and personal sacrifice for the public good. This civic mode of being is increasingly foreign today. Roman citizens were more aware of the land and the climate. They were more self-reliant and leery of concentrated power. They were more in tune with the sacrifices of war. In a modern world beset by environmental challenges; military conflicts waged by technocrats, professionals, and drones; and large, bureaucratic nation-states where average citizens offer little participation in politics, especially in the ways they authorize and fight wars, the story of the ancient republican is more important than ever before.

Next page