PENGUIN BOOKS

MAGNA CARTA

Dan Jones is the author of The Plantagenets: The Warrior Kings and Queens Who Made England , a #1 international bestseller and New York Times bestseller, and The Wars of the Roses , which charts the story of the fall of the Plantagenet dynasty and the improbable rise of the Tudors. He writes and presents the popular Netflix series Secrets of Great British Castles and appeared alongside George R. R. Martin in the official HBO film exploring the real history behind Game of Thrones . He was closely involved in the British Librarys landmark unification of the four remaining original copies of the Magna Carta to mark the charters eight hundredth anniversary. He is also the author of Summer of Blood: Englands First Revolution and is currently working on a history of the Knights Templar due out in fall 2017.

ALSO BY DAN JONES

The Plantagenets:

The Warrior Kings and Queens Who Made England

The Wars of the Roses:

The Fall of the Plantagenets and the Rise of the Tudors

Summer of Blood:

Englands First Revolution

PENGUIN BOOKS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

penguin.com

First published in the United States of America by Viking Penguin, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC, 2015

Published in Penguin Books 2016

Copyright 2015 by Daniel Jones

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Portions of this book have appeared in different form in Dan Joness Magna Carta: The Making and Legacy of the Great Charter , published in Great Britain by Head of Zeus. Copyright 2014 by Dan Jones.

ILLUSTRATION CREDITS

Insert page 1: (top)

Insert page 2: (top)

Insert page 3: (top)

Insert page 4: (top)

Insert page 5:

Insert page 6: (top)

Insert page 7: (top left)

Insert page 8: (top)

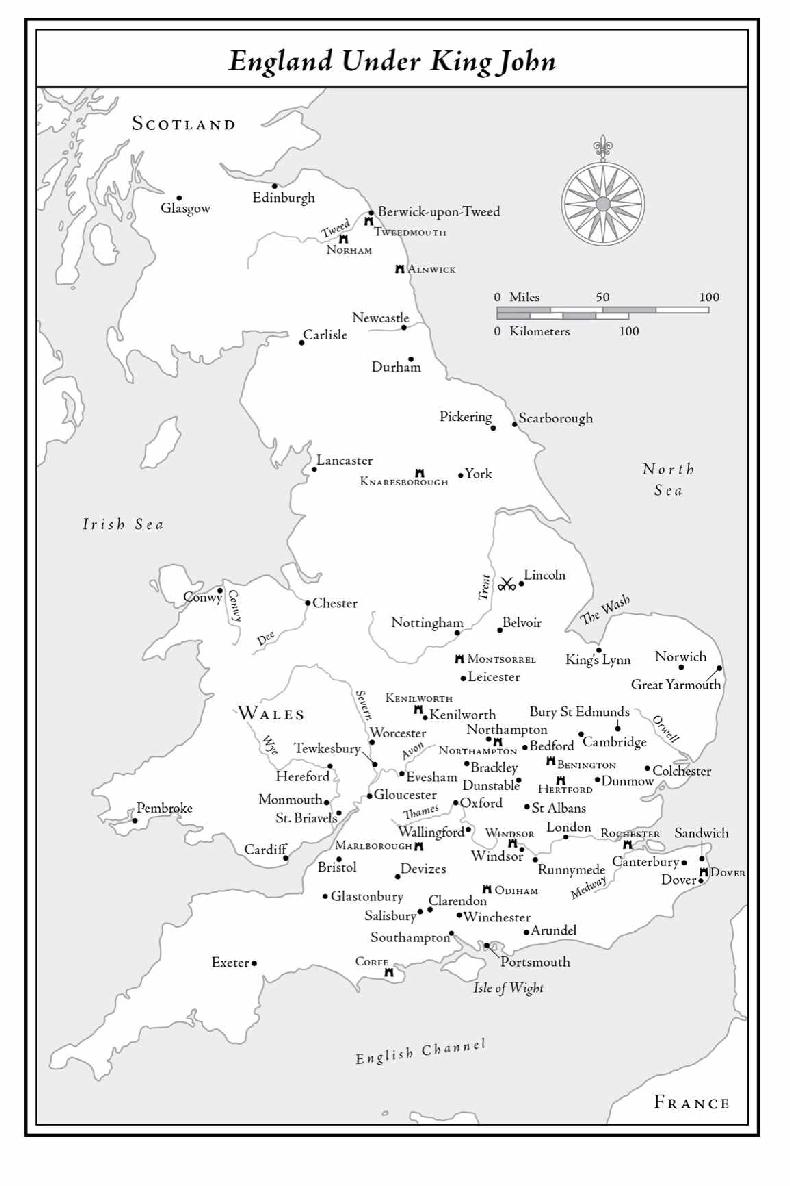

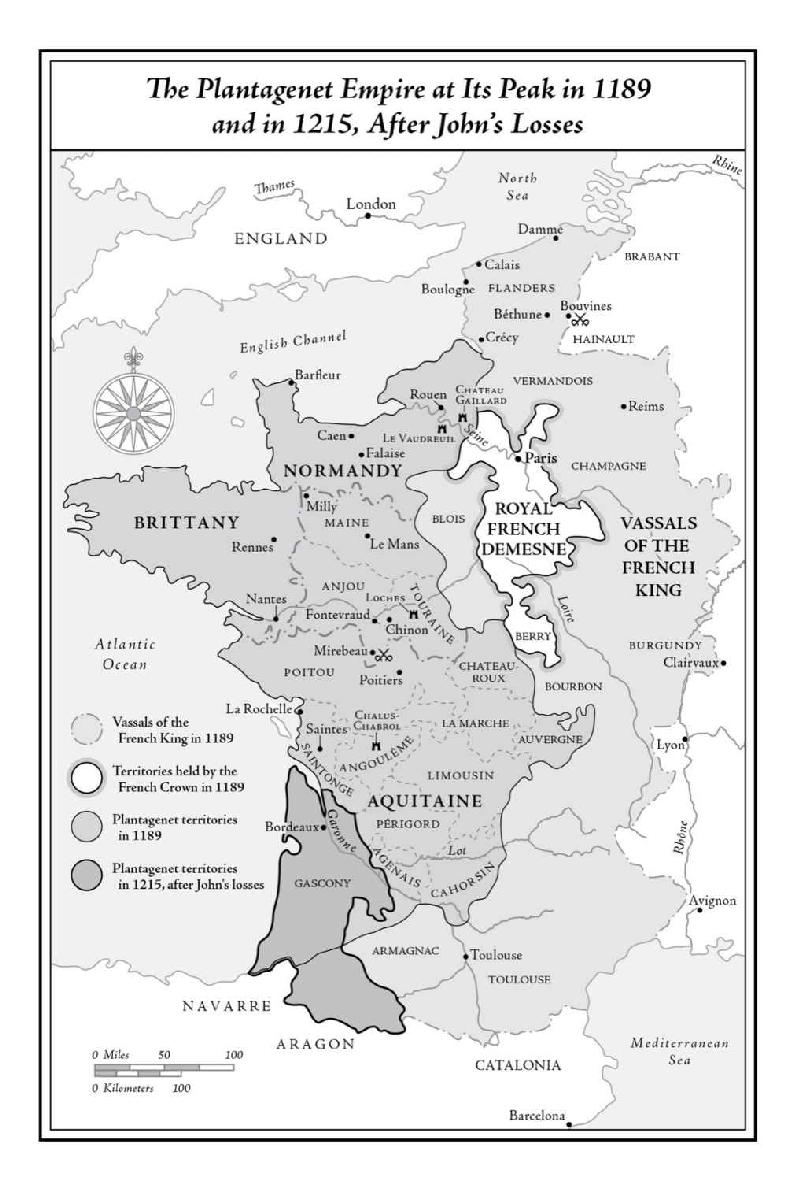

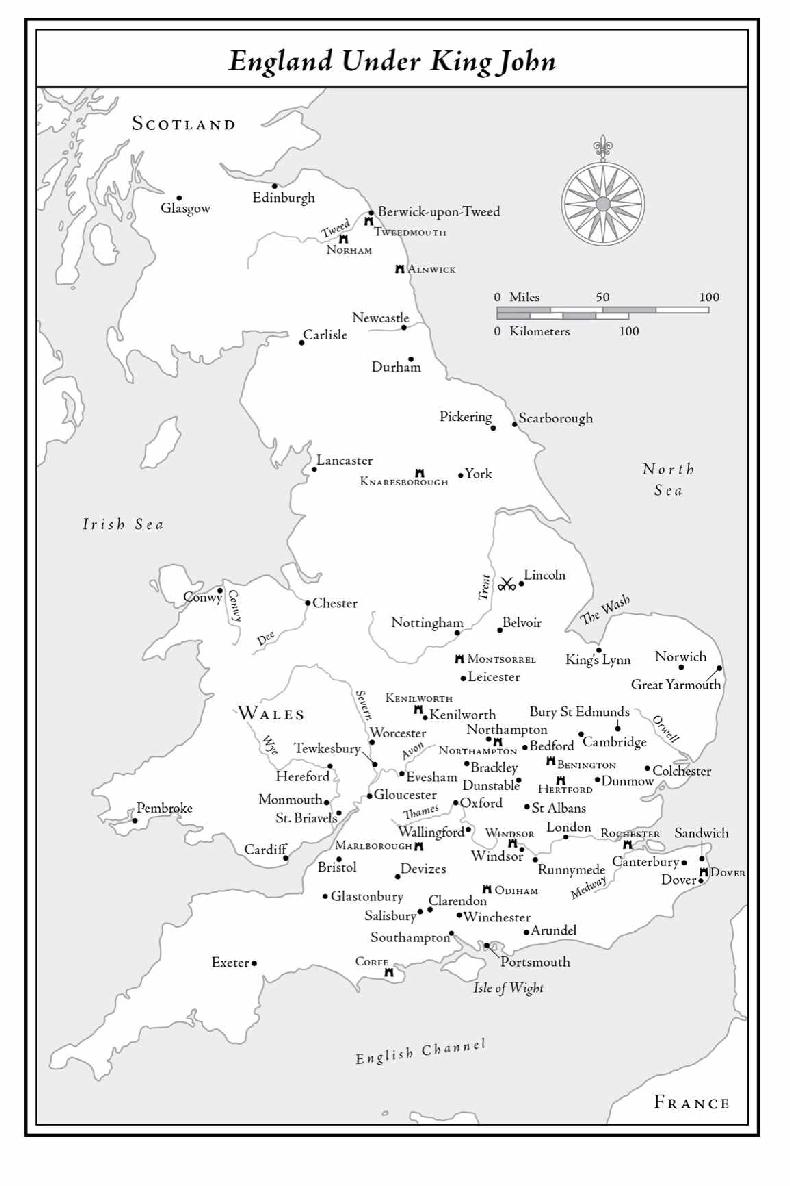

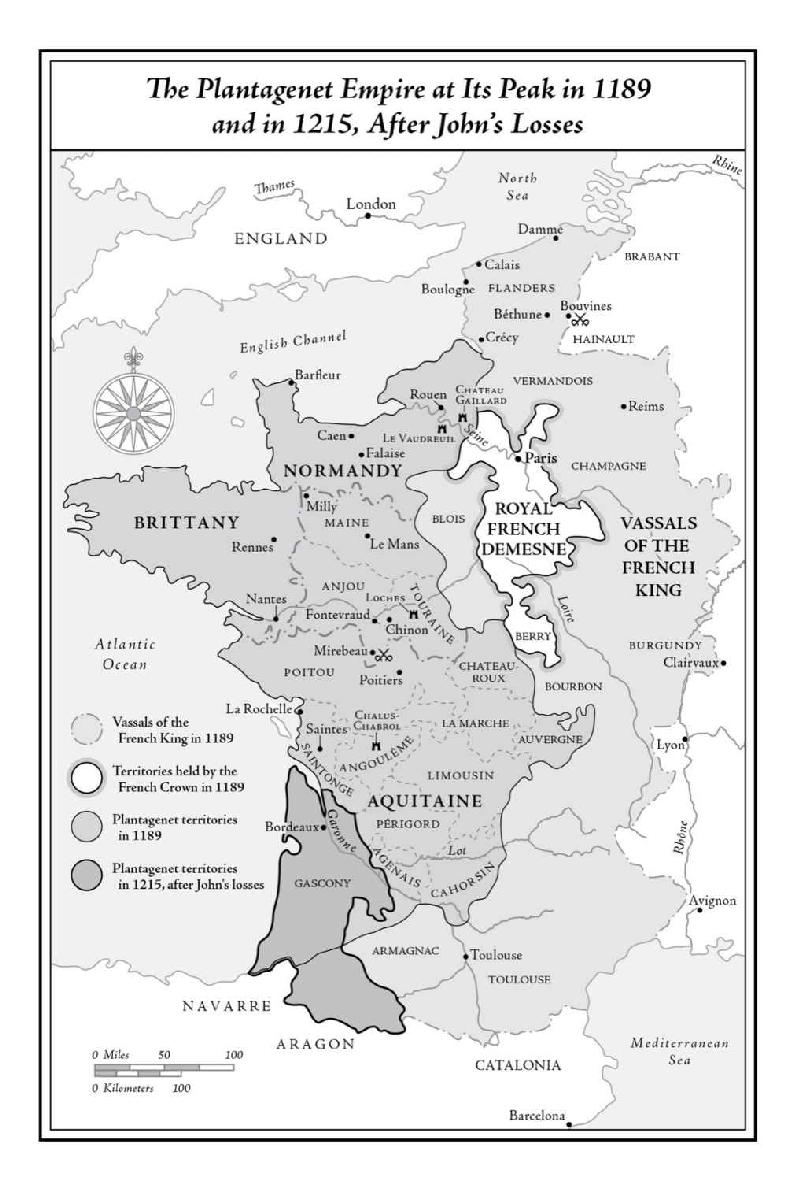

Maps by Jeffrey L. Ward

Ebook ISBN: 9780698186422

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers, Internet addresses, and other contact information at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party Web sites or their content.

Cover design: the Book Designers

Cover image: King Johns seal, as affixed to the Magna Carta

Color lithograph by Dan Escott, 192887 / Private Collection / Look and Learn / Bridgeman Images

Version_2

In memoriam

H. E.

But let no one, however rich, flatter himself that he can misbehave with impunity, for of such people it is written, The powerful shall suffer powerful torments.

The Dialogue of the Exchequer

Richard FitzNigel, 1177c. 1189

Contents

Introduction

E IGHT HUNDRED YEARS after it was first granted beneath the trees of Runnymede, by the fertile green banks of the river Thames, the Magna Carta is more famous than ever. This is strange. In its surviving formsthere are four known original charters dating from June 1215the Magna Carta is something of a muddle, a collection of promises extracted in bad faith from a reluctant king, most of which concern matters of arcane thirteenth-century legal principle. A few of these promises concern themselves with high ideals, but they are few and far between, vague and idealistic statements slipped between longer and more perplexing sentences describing the customary fee that a baron ought to pay a king on the occasion of coming into an inheritance, or the protocols for dealing with debt to the Crown, or the regulation of fish traps along the rivers Thames and Medway.

For the most part the Magna Carta is dry, technical, difficult to decipher, and constitutionally obsolete. Those parts that are still frequently quotedclauses about the right to justice before ones peers, the freedom from being unlawfully imprisoned, and the freedom of the Churchdid not mean in 1215 what we often wish they would mean today. They are part of a document drawn up not to defend in perpetuity the interests of national citizens but rather to pin down a king who had been greatly vexing a small number of his wealthy and violent subjects. The Magna Carta ought to be dead, defunct, and of interest only to serious scholars of the thirteenth century.

Yet it is very much alive, one of the most hallowed documents in the world, revered from the Arctic Circle to the antipodes, written into the constitutions of numerous countries, and admired as a foundation stone in the Western traditions of liberty, democracy, and the rule of law. How did that happen?

The Magna Carta was a peace treaty born of a serious collapse in relations between John, the third Plantagenet king of England, and his barons. The reasons for that collapse will be discussed in this book, but the basic thrust of events was simple. A large party of Johns barons, with the assistance of churchmen guided by the impressive archbishop of Canterbury, Stephen Langton, demanded that the king confirm in writing (and certify with his Great Seal) a long list of rights and royal obligations that they felt he and his predecessors had neglected, ignored, and abused for too long. These rights and obligations were conceived in part as a return to some semi-imaginary ancient law code that had governed a better, older England, which lay in the historical memory somewhere between the days of the last Saxon king, Edward the Confessor, and the more recent times of Johns great-grandfather, Henry I.

The Magna Carta touched on matters of religion, tax, justice, military service, feudal payments, weights and measures, trading privileges, and urban government. Occasionally it reached for grand principle: Famously, John was forced to promise that no free man is to be arrested, or imprisoned, or disseized, or outlawed, or exiled, or in any other way ruined, nor will we go or send against him, except by the legal judgment of his peers or by the law of the land and that to no one will we sell, to no one will we deny or delay, right or justice. But for the most part what was at issue in 1215 was a tight-knit, technical, and often quite dull shopping list of feudal demands that was mainly of interest to (and in the interests of) a tiny handful of Englands richest and most powerful men. The Magna Cartas terms applied only to free men, who were then at best 10 percent or 20 percent of Englands adult population.

The main novelty of the Magna Carta, often overlooked, was the fact that it proposed a neat but flawed mechanism for ensuring that the king stuck to what he had promised to do. If John reneged on the charter, his barons would renounce their personal loyalty to the king, on which the whole feudal structure of society depended, and start a war. This grave threat was reflected in the words of the charter itself, in which John acknowledged that if he failed to keep the promises he had made, then his barons could distrain and distress [him] in all ways possible, by taking castles, lands, possessions... saving our person and the persons of our queen and children.