www.headofzeus.com

Contents

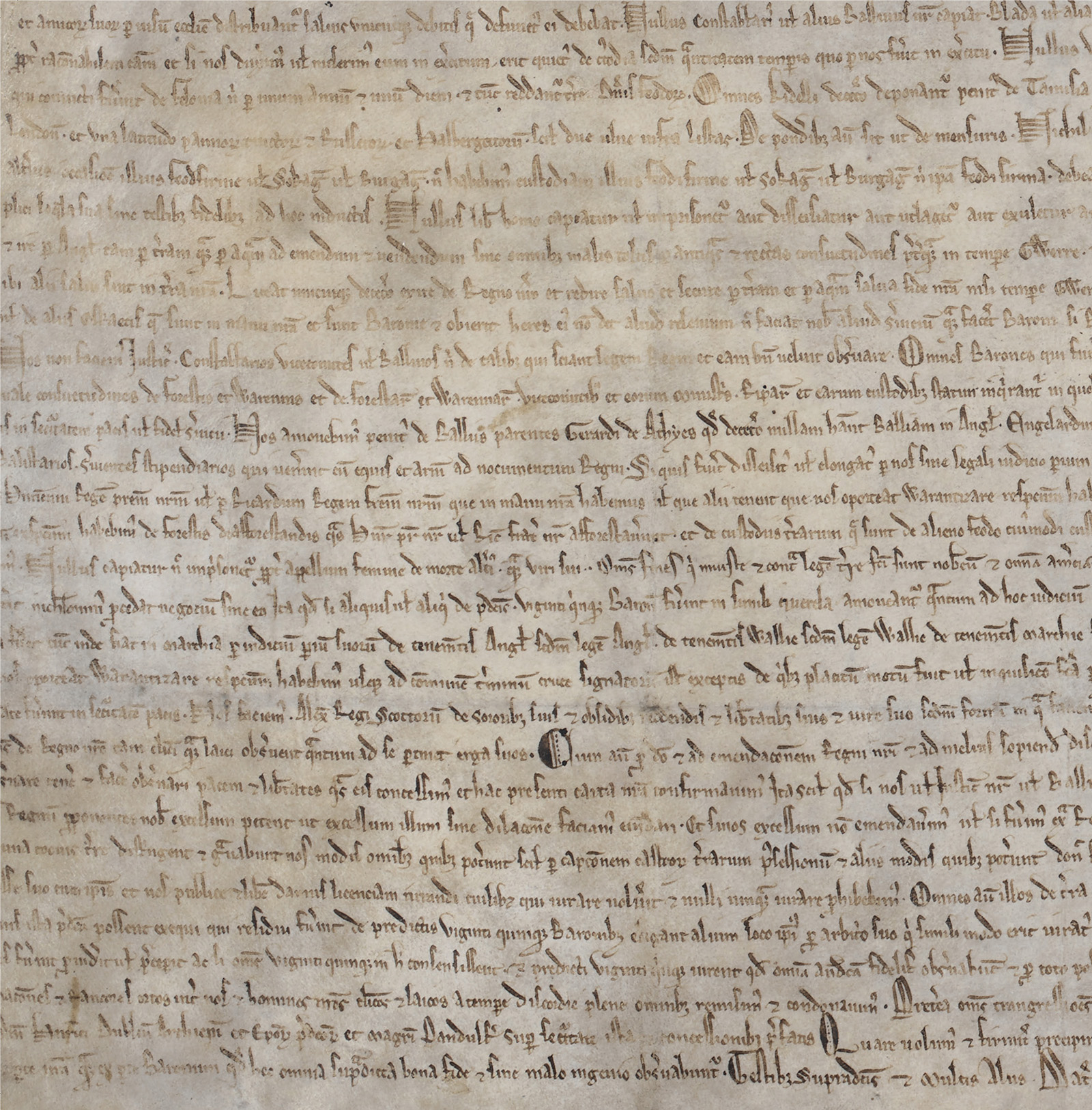

The Fame of Magna Carta

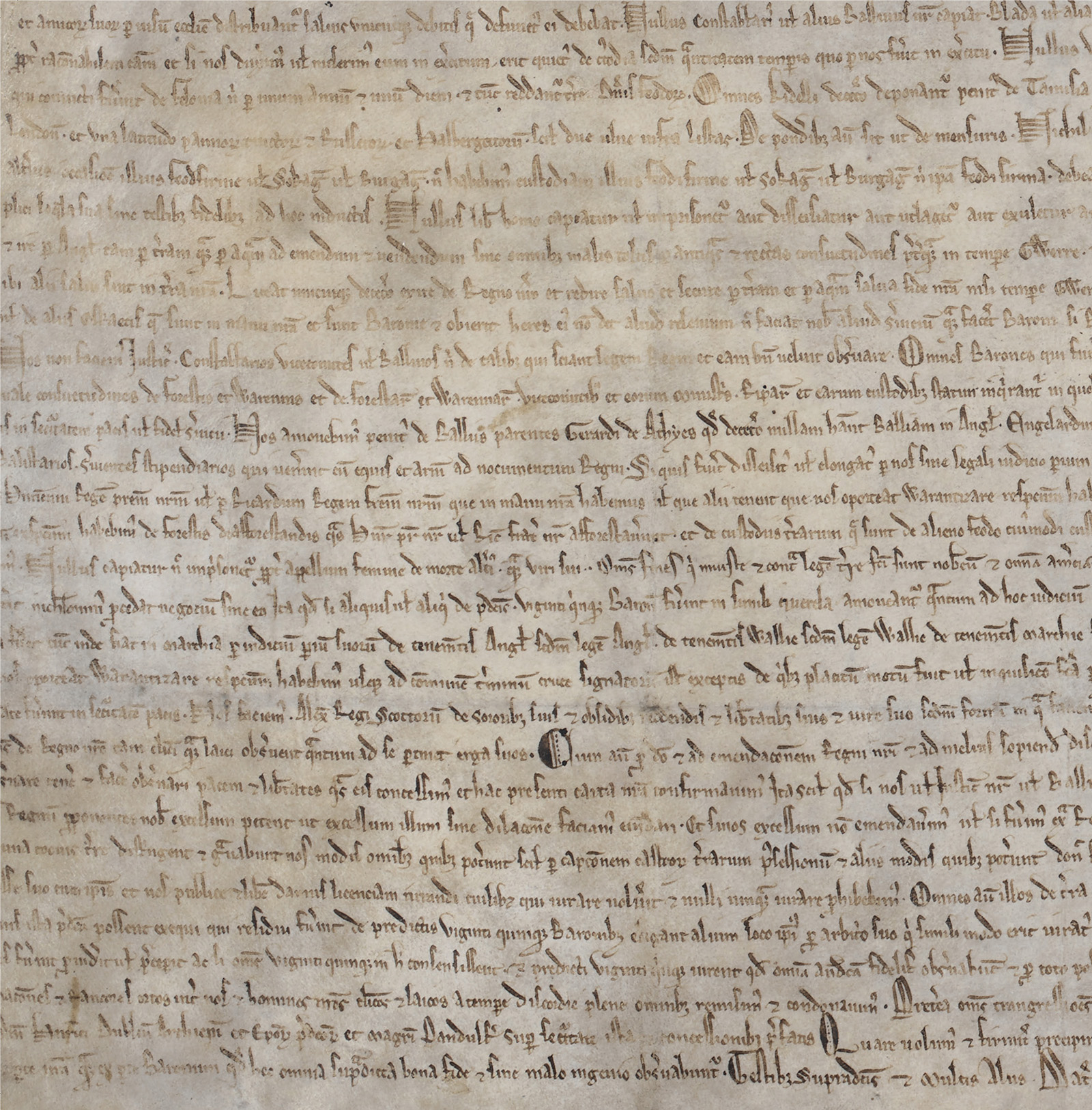

Eight hundred years after it was first agreed beneath the oak trees of Runnymede, by the fertile green banks of the River Thames, Magna Carta is more famous than ever. This is strange. In its surviving forms and there are four known original charters dating from June 1215 Magna Carta is something of a muddle. It is a collection of promises extracted in bad faith from a reluctant king, most of which concern matters of arcane thirteenth-century legal principle. A few of these promises concern themselves with high ideals, but those are few and far between, vague and idealistic statements slipped between longer and more perplexing sentences describing the customary fee that a baron ought to pay a king on the occasion of coming into an inheritance, or the protocols for dealing with debt to the Crown, or the regulation of fish-traps along the Thames and the Medway.

For the most part, Magna Carta is dry, technical, difficult to decipher and constitutionally obsolete. Those parts that are still frequently quoted clauses about the right to justice before ones peers, the freedom from being unlawfully imprisoned and the freed om of the Church did not mean in 1215 what we often wish they would mean today. They are part of an agreement drawn up not to defend, in perpetuity, the interests of national citizens, but rather to pin down a king who had been greatly vexing a very small number of wealthy and violent barons. Magna Carta ought to be dead, defunct and only of interest to serious scholars of the thirteenth century.

Yet it is very much alive, one of the most hallowed documents in the world, revered from the Arctic Circle to the Antipodes, written into the constitutions of numerous countries, and admired as a foundation stone in the Western traditions of liberty, democracy and the rule of law. How did that happen?

This book tells the story of Magna Carta its background, its birth, its almost instantaneous failure, its slow resurrection and its mutation into the thing it is today: a historical palimpsest onto which almost any dream can be written. It looks at Magna Cartas place in the history of medieval England and modern Britain. It describes briefly how the charter was exported to America and the wider world. It considers how Magna Carta is discussed in the popular media today, as we enter the ninth century of its existence. It also presents the text in its Latin form and, more accessibly, in English translation, so that readers can, as it were, go straight to the horses mouth.

Mostly, though, this book seeks to explain the historical context from which Magna Carta emerged in the early thirteenth century, during the reign of King John. His rule was a litany of troubles, which included the loss of Normandy in 1204, a great argument with Pope Innocent III (in the course of which Englands churches closed and John himself was excommunicated), vicious personal squabbles with barons whom the king had once called his friends, an utterly miserable invasion of France in 1214, and finally civil war in 121517, as a result of which Magna Carta was produced and Johnsuccumbed to fatal illness. I have told this story in detail, and have tried to describe how the policies John pursued built towards Magna Carta in 1215, and why his barons felt so compelled to shackle him as they did.

This book does not attempt to drastically rehabilitate John, who was satirized so deliciously in Sellar and Yeatmans 1066 and All That as an awful king. It does, however, aim to show that Magna Carta had far deeper roots than Johns reign. While Johns own, often appalling, behaviour was much to blame for the chaos that rained down upon him during his final years, he was not by any means the sole architect of his woes. This is a point recognized both by modern historians and by men who lived in the age of Magna Carta. The chronicler Ralph of Coggeshall, writing in the middle of the thirteenth century, observed that Magna Carta was not created simply to restrain John but also to end the evil customs which the father and brother of the king had created to the detriment of the Church and kingdom, along with those abuses which the king had added. the direction of an important historical truth: we cannot simply view Magna Carta as a bill of protest and remedy aimed merely at the scandalous and unlucky John, but as a howl of historical complaint that was directed, at least on some level, against two generations of perceived abuse.

To begin this story, therefore, we must reach back sixty years before 1215, to the time of Johns father, Henry II.

Dan Jones

Battersea, London

October 2014

England Reordered

11541189

During his reign he would take effective command of Brittany and assert his right to the lordship of Ireland. His power therefore stretched from the borders of Scotland to the Pyrenees, and they encompassed virtually the entire western seaboard of greater France. Indeed, Henrys political tentacles stretched even further afield than that, for he had interests and alliances from Saxony to Sicily, and from Castile to the Holy Land. Few European monarchs since Charlemagne had exercised control over such vast territories, and few medieval kings would rule with such political agility, ruthlessness and skill.

Henrys physical stamina allowed him to spend almost his whole life moving about his lands, tolerant of the discomforts of dust and mud travelling in unbearably long stages, and enjoying, according to Walter Map, the fact that his physical exertions prevented him from getting fat.

Henry inherited the English crown in a political deal to end a civil war that had raged for nineteen years. Contemporaries called the war the Shipwreck. Historians now refer to it as the Anarchy. Either way, it was a struggle waged between two grandchildren of William the Conqueror Henrys mother, Matilda, and her cousin, King Stephen, both of whom claimed to be the legitimate heir of Henry I (r. 110035).

Neither contender for the throne could summon enough military or political support to enforce their claim, and as a result England was torn for a generation between two hostile factions. Royal authority across the realm collapsed, and the horrors of civil war descended: arson, torture, bloodshed, murder, robbery, laying waste the land, starvation, economic turmoil and a widespread failure of justice. Every man began to rob his neighbour, wrote the author of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. It was said openly that Christ and his saints were asleep. The Treaty of Winchester (1153) brought an end to the conflict by naming Henry as Stephens royal heir. When Stephen died the following year and Henry took power, his first duty was to restore firm royal rule to a land that had not known effective governance for a generation.

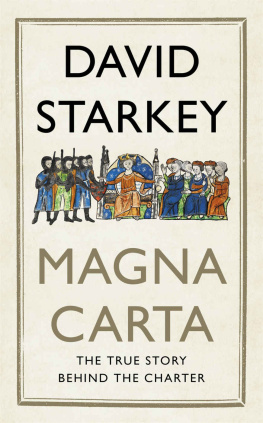

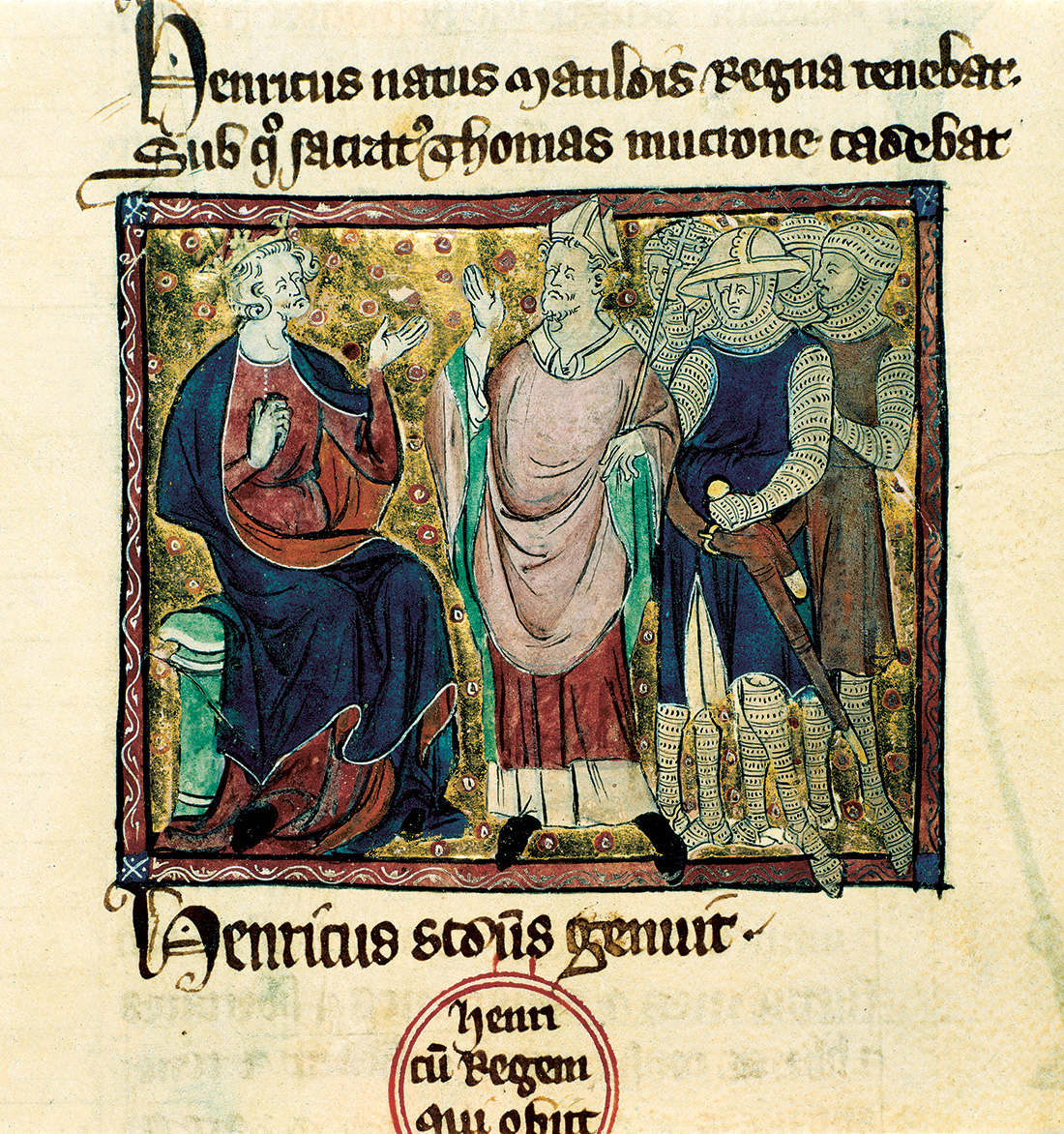

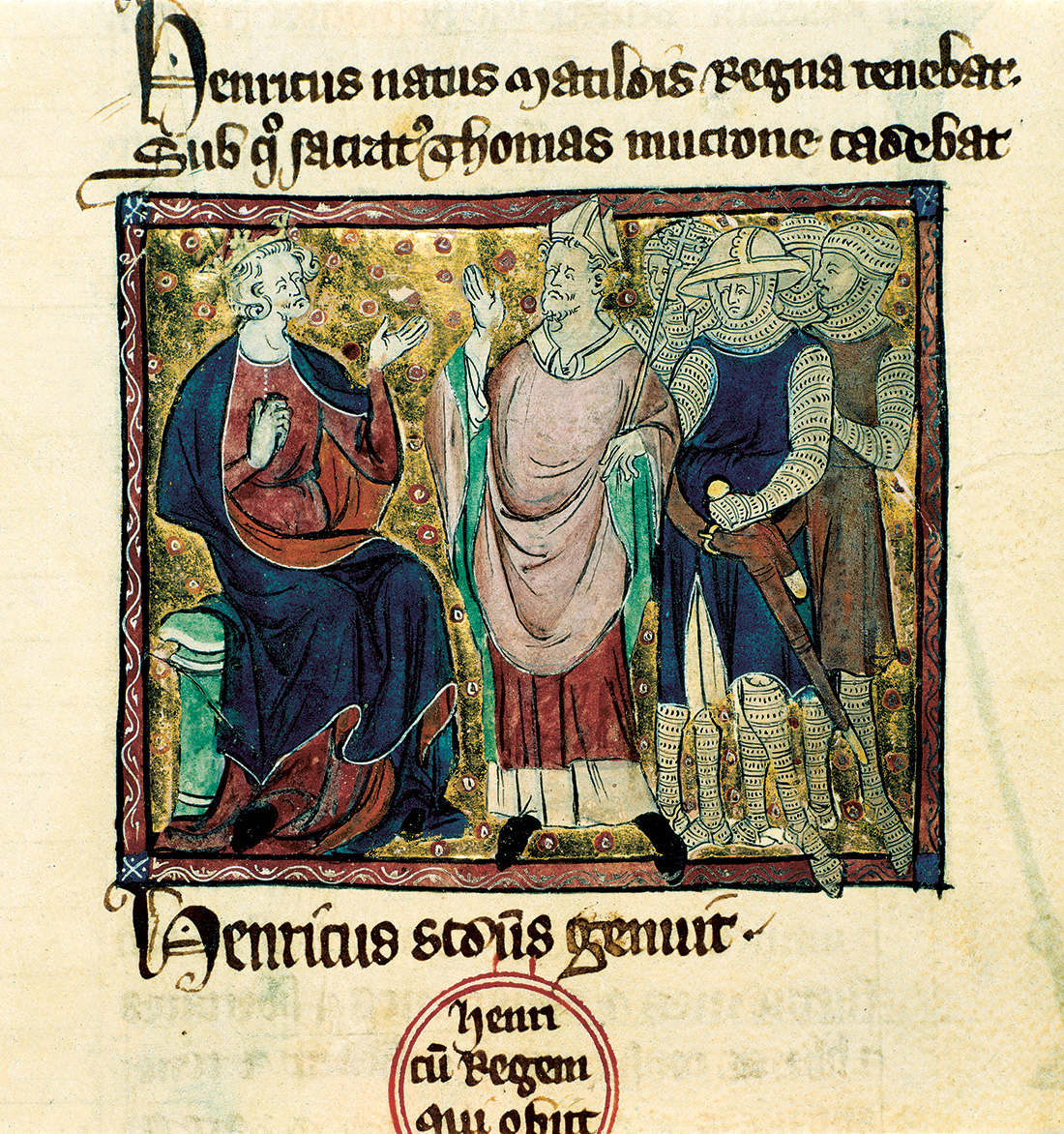

A miniature from Claudius D. II, a legal treatise in the Cotton collection of medieval manuscripts now housed in the British Library. It shows Henry II remonstrating with Thomas Becket, while knights ominously finger their swords. Henry established a Plantagenet empire around the English Crown, and developed an intense and efficient system of government to rule it. But, as did John later on, he fell into dispute with the English Church, represented here by Becket. In 1215 Magna Carta would be as much an attempt to rein back Henrys legacy of royal power as it was an attempt to curtail Johns more recent abuses.

Next page