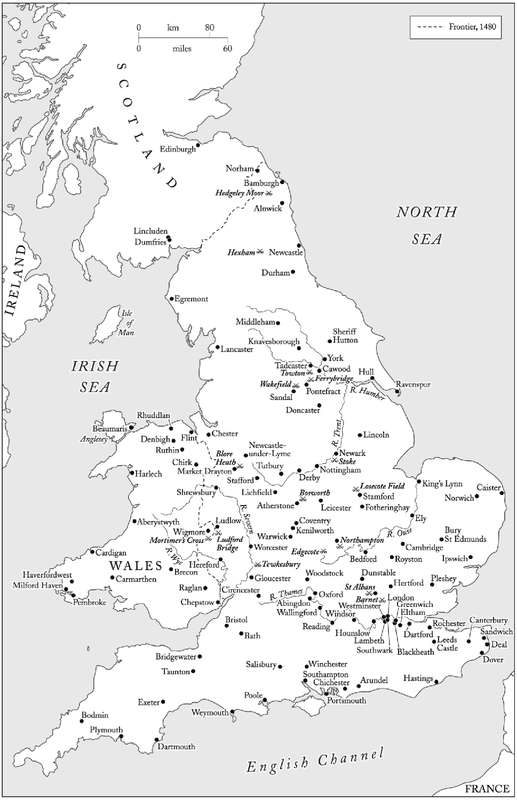

2. England and Wales in the Fifteenth Century

The names of principal characters in this book have generally been modernised for the sake of familiarity and consistency. Thus Nevill becomes Neville, Wydeville becomes Woodville, Tudur becomes Tudor, and so on. Latin, French and archaic English sources have been translated or rendered into modern English except in a very few cases where original spellings have been maintained to illustrate a historical point.

Where particularly pertinent, sums of money have been translated into modern currencies with the assistance of the conversion tool at http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/currency/, which gives modern values for ancient, and also has a purchasing power function. Readers should be aware, however, that the conversion of monetary values across the centuries is a perilously inexact science, and that the figures given are for rough guidance only. As an approximation, 100 in 1450 would be worth 55,000 (or $90,000) today. The same sum would represent ten years salary for an ordinary English labourer in the mid-fifteenth century.

Where a distance between two places is given, it has usually been calculated using Google Maps Walking Directions, and thus tends to be calculated according to the fastest route via modern roads.

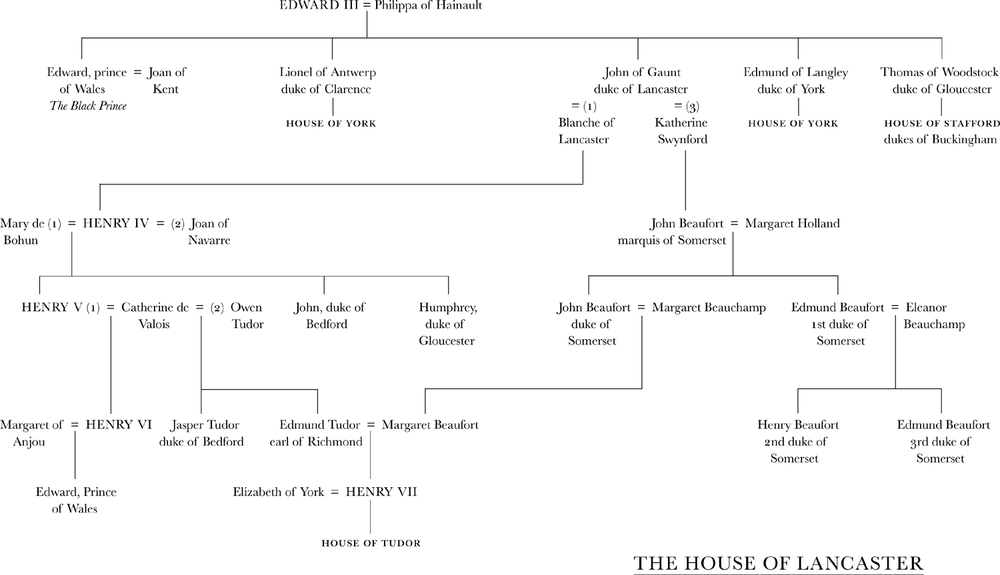

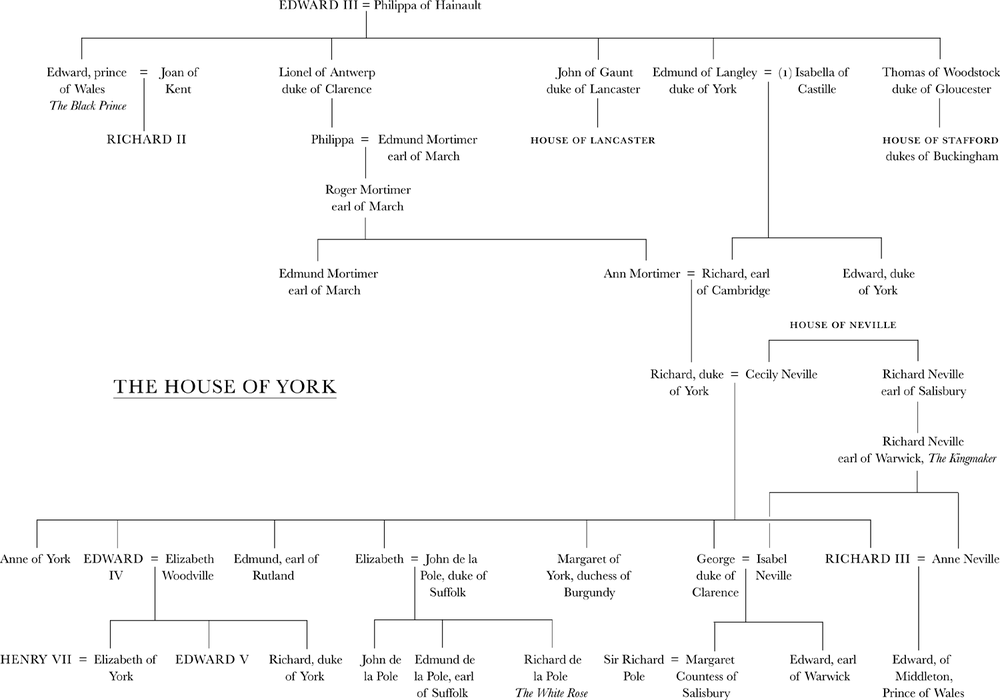

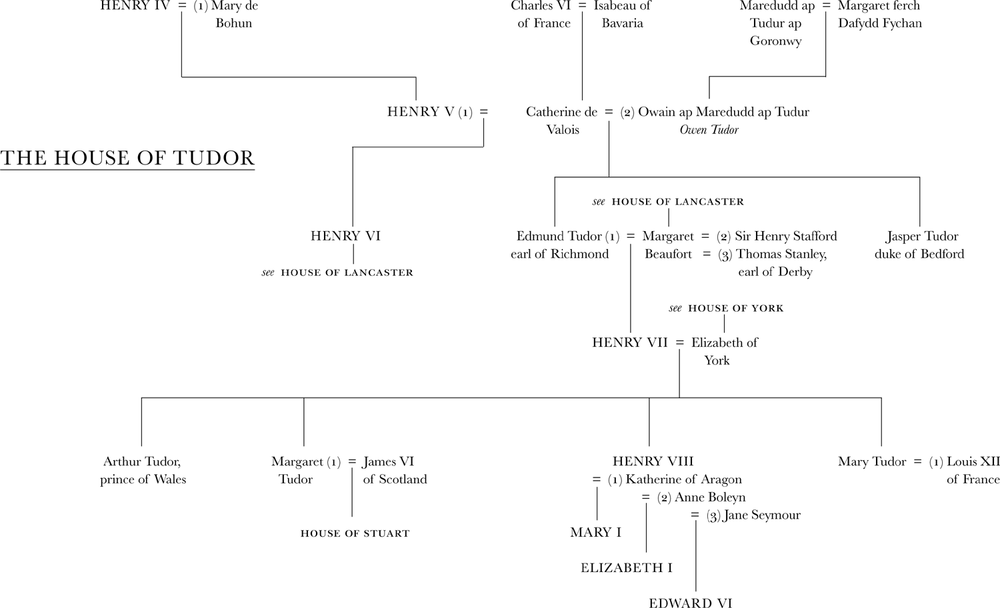

The family trees presented at the start of this book are designed to clarify the complex dynastic links described later in the text. For reasons of space and sense, these have been simplified. In some places, siblings have been placed out of order of age.

Who wot nowe that ys here

Where he schall be anoder yere?

ANON. (1445)

For Gods sake, let us sit upon the ground

And tell sad stories of the death of kings;

How some have been deposed; some slain in war,

Some haunted by the ghosts they have deposed;

Some poisond by their wives: some sleeping killd;

All murderd: for within the hollow crown

That rounds the mortal temples of a king

Keeps Death his court

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, Richard II (c.1595)

At seven oclock in the morning on Friday 27 May 1541, within the precincts of the Tower of London, an old woman walked out into the light of a spring day. Her name was Margaret Pole. By birth, blood and lineage she was one of the noblest women in England. Her father, George duke of Clarence, had been the brother to a king and her mother, Isabel Neville, had in her time been co-heir to one of the greatest earldoms in the land. Both parents were now long gone, memories from another age and another century.

Margarets life had been long and exciting. For twenty-five years she had been the countess of Salisbury, one of only two women of her time to hold a peerage in her own right. She had until recently been one of the five wealthiest aristocrats of her generation, with lands in seventeen counties. Now, at sixty-seven ancient by Tudor standards she appeared so advanced in age that intelligent observers took her to be eighty or ninety.

Like many inhabitants of the Tower of London, Margaret Pole was a prisoner. Two years previously she had been stripped of her lands and titles by an act of parliament which accused her of having committed and perpetrated diverse and sundry other detestable and abominable treasons against her cousin, King Henry VIII. What these treasons were was never fully evinced, because in truth Margarets offences against the crown were more general than particular. Her two principal crimes were her close relation to the king and her suspicion of his adoption of the new forms and doctrines of Christian belief that had swept through Europe during the past two decades. For these two facts, the one of birthright and the second of conscience, she had lived within Londons stout, supposedly impervious riverside fortress, which bristled with cannon from its whitewashed central tower, for the past eighteen months.

Margaret had lived well in jail. Prison for a sixteenth-century aristocrat was supposed to be a life of restricted movement tempered by decent, even luxurious conditions, and she had been keen to ensure that her confinement met the highest standard. She expected to serve a comfortable sentence, and when she found the standards wanting, she complained. Before she was moved to London she had spent a year locked in Cowdray House in West Sussex, under the watch of the unenthusiastic William Fitzwilliam, earl of Southampton. The earl and his wife had found her spirited and indignant approach to incarceration rather tiresome and had been glad when she was moved on.