Crown and Country

A History of England through the Monarchy

DAVID STARKEY

To all those who worked with me on the Channel 4

Monarchy series for helping me understand history

better and write it more clearly

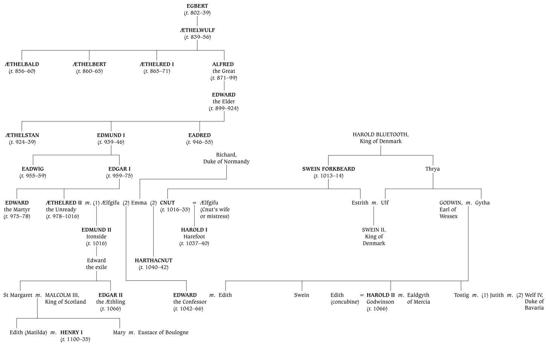

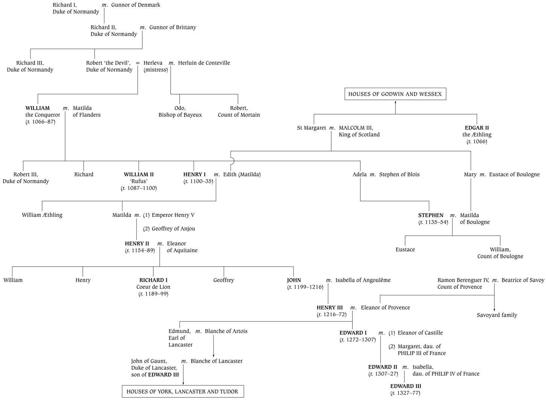

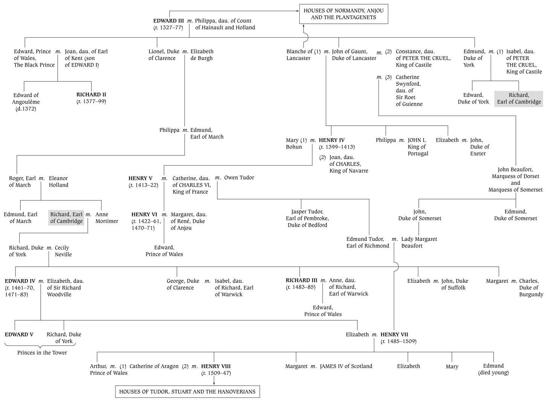

Contents

THIS BOOK IS THE STORY of the crown of England and of those who wore it, intrigued for it and died for it. They include some of the most notable figures of English and British history: Alfred the Great and William the Conqueror, who shaped and reshaped England; the great Henrys and Edwards of the Middle Ages, who made England the centre of a vast European empire; Henry VIII, whose mere presence could strike men dumb with fear; Elizabeth I, who remains as much a seductive enigma to us as she was to her contemporaries; and Charles I, who redeemed a disastrous reign with a noble, sacrificial death as he humbled himself, Christ-like and self-consciously so, to the executioners axe.

Such figures leap from the page of mere history into myth and romance. I have painted these great royal characters and the dozens of other monarchs, who, rightly or wrongly, have left less of a memory behind with as much skill as I could.

But this is not a history of Kings and Queens. And its approach is not simply biographical either. Instead, it is the history of an institution: the Monarchy. Institutions and monarchy most of all are built of memory and inherited traditions, of heirlooms, historic buildings and rituals that are age-old (or at least pretend to be). All these are here, and, since I have devoted much of my academic career to what are now called Court Studies, they are treated in some detail.

But the institution of monarchy and I think this fact has been too little appreciated is also about ideas. Indeed, it is on ideas that I have primarily depended to shape the structure of the book and to drive its narrative. These are not the disembodied, abstract ideas of old-fashioned history. Instead, I present them through lives of those who formulated them. Sometimes these were monarchs; more usually they were advisers and publicists. Such men at least as much as soldiers and sailors were the shock-troops of monarchy. They shaped its reaction to events; even, at times, enabled it to seize the initiative. When they were talented and imaginative, monarchy flourished; when they were not, the crown lost its sheen and the throne tottered.

So monarchy depends on its servants: its advisers and ideologues; its painters, sculptors and architects, and not least its historians. And these, too, are given voice, sometimes as chorus to the swelling scene, occasionally as actors themselves.

The result is a task completed. It began in 2004 with the publication of The Monarchy of England: The Beginnings . That book covered the period from the fall of Roman Britain to the Norman Conquest and its aftermath, and was intended to be the first of three volumes to accompany a Channel 4 series of the same name. A further volume, Monarchy: From the Middle Ages to Modernity , appeared in 2006. But the Middle Ages themselves remained untreated. This book brings together the two previously published volumes. And it fills in the missing centuries in the same style and with similar emphases.

I have also changed the books title. Monarchy was chosen because of the fashion at the time for portentous one-word titles for major television series. And it did the job well enough. But Crown and Country does it better. The crown is the oldest English institution and the most glittering. But its story, as I tell it, is finally the means to an end: the history of England herself.

The Red House

Barham, Kent

July 2010

SOMETIMES, EVEN WHEN you are a case-hardened professional, you see history differently. I had one such moment when I first visited the Great Hall of the National Archives in Washington. I was faintly shocked by the way in which the Constitution and the Bill of Rights were displayed, like Arks of the Covenant, on a dimly lit altar and between American flags and impossibly upright American marines.

But what really struck me was the presence of a copy of Magna Carta. It was, as it were, in a side chapel. Nevertheless, here it was, this archetypically English document, in the American archival Holy of Holies.

It was placed there out of the conviction that it was the ancestor, however remote, of the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. And its presence set me thinking. Was this assumption correct? Does it help explain current concerns like Britains, or Englands, reluctance to be absorbed in the European Union? Does it mean that there is an Anglo-Saxon way and a European way, as the French undoubtedly think? Does the difference derive from the contrast between Roman Law and English Common Law? Is it, finally, England versus Rome?

The first part of this book attempts to answer some of these questions. It uses the medium of narrative, which I think is the only proper means of historical explanation. And it goes back to the beginning, which is the only right place to start.

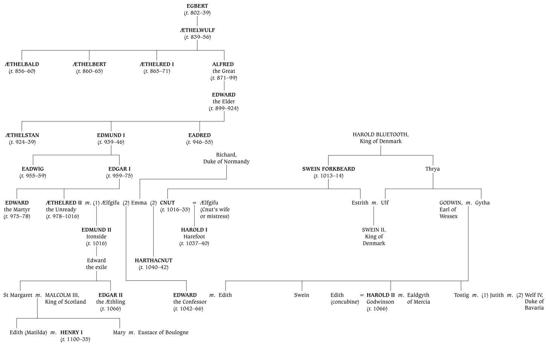

Indeed, if I may be excused Irish, it goes back before the beginning. The idea of the English does not appear until the eighth century, and the reality of England not till two hundred years later still. But I start a millennium earlier with the Roman invasions and occupation of Britain. I do so for two reasons. The first is that the great Anglo-Saxon historian Bede, who, more than anyone else, invented the idea of England, thought that this was the right place to start his Ecclesiastical History of the English People. The second is that Rome is indeed our common mother and is the fount from which all modern western European countries spring.

But, in the case of England, Rome is at best a stepmother. There is, uniquely in the Western Empire, an absolute rupture between the Roman province of Britannia and the eventual successor-state of Anglo-Saxon England. Elsewhere, in France, Italy or Spain, there are continuities: of language, laws, government and religion. In Britain there are none. Instead the Anglo-Saxon invaders of the fifth century found, or perhaps made, a tabula rasa .

This is normally regretted. Civilization was destroyed, the common story goes, and the Dark Ages began. I am not so sure. For Rome was not as civilized as we think and the Dark Ages at least in Anglo-Saxon England were by no means so gloomy. The roots of the misunderstanding, I think, lie in the importance we attach to material culture. We too live in a comfortable age, so we are impressed too impressed with the apparatus of Roman comfort: the baths, the sanitation, the running water, the central heating and the roads.

All these are, indeed, very sophisticated. But the politics that underpinned them was surprisingly crude. Not only was the Empire a mere military despotism, it was also peculiarly mistrustful of any form of self-help, much less self-government, on the part of its subjects. This is shown by a famous exchange of letters between the Emperor Trajan and the senatorial aristocrat and man of letters Pliny the Younger, who was then governor of the province of Bithynia in Asia Minor. The important provincial city of Nicomedia, Pliny informed the emperor, had suffered a devastating fire. Might he encourage the citizens to set up a guild of firemen to fight future conflagrations? On no account, replied the emperor, since such bodies, whatever their ostensible purpose, become fronts for faction and political dissent.

Next page