Contents

About the Author

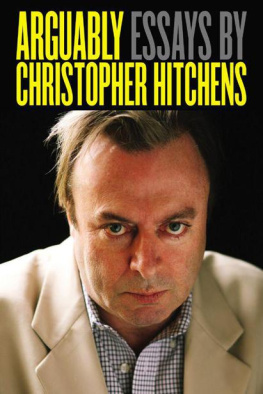

CHRISTOPHER HITCHENS was born April 13, 1949, in England and graduated from Balliol College at Oxford University. The father of three children, he was the author of more than twenty books and pamphlets, including collections of essays, criticism, and reportage. His book, God Is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything, was a finalist for the 2007 National Book Award in the United States and was an international bestseller. His bestselling memoir, Hitch-22, was a finalist for the 2010 National Book Critics Circle Award for autobiography. His 2011 bestselling omnibus of selected essays, Arguably, was named by the New York Times as one of the ten best books of the year. A visiting professor of liberal studies at the New School in New York City, he was also the I.F. Stone professor at the Graduate School of Journalism at the University of California, Berkeley. He was a columnist, literary critic, and contributing editor at Vanity Fair, The Atlantic, Slate, Times Literary Supplement, The Nation, New Statesman, World Affairs, Free Inquiry, among other publications. He died in Houston, Texas, on December 15, 2011. His posthumous memoir, Mortality, will be published in the fall of 2012.

About this Ebook

This ebook was originally published as a print pamphlet in 1990 as part of the Chatto Counterblasts series. It is reproduced here without alteration; some of the references are specific to that period, but Hitchens arguments and themes are as relevant today if not more so as when it was first published.

Part of the Brain Shots series, the pre-eminent source for high quality, short-form digital non-fiction.

The Monarchy

A Critique of Britains Favourite Fetish

Christopher Hitchens

NIGHT IS COMING on, and the urgent, meretricious tones of the television news muzak are heard. We know that this strident, bombastic noise is a subliminal appeal to think of news as part drama, part sensation and part entertainment (like the fanfares from the telescreen in Orwells dystopia) but we are won over to give it another chance. What is being heralded by this racket, this time? It might be fire, flood or famine; assassination or invasion; coup or communiqu. Is it just tomorrows talking point, or is it one of those events that stay imprinted on the memory for good? Well, neither actually. On the evening Im thinking of, the first and longest bulletin from a potential world of agony and ecstasy was one which sounded a false alarm. The Queen Mother had been incommoded by a morsel of food wedged in her throat.

What is this? Why, when the subject of royalty or monarchy is mentioned, do the British bid adieu to every vestige of proportion, modesty, humour and restraint? Why, in this dubious and sentimental cause, will they even abandon their claim to a stiff upper lip? We read with revulsion about those countries where the worship of mediocre individuals the Ceauescu dynasty in Romania comes to mind has become even more of an offence than it has a bore. We are supposed to know enough to recoil from sickly adulation, and from its counterpart, which is hypocrisy and envy. We learn from history the subtle and deadly damage that is done to morale by the alternation between sycophancy and resentment. Yet the unwholesome cult of the Windsors and the Waleses is beginning to turn morbid before our eyes.

Either at your throat or at your feet. So runs the old maxim about Fleet Street. Fair-weather in its affections, and with a shrewd eye for the market forces in opinion that have become a secular religion, the mouthpieces of the New Britain trade on love and hate by debasing and cheapening both. At one moment, the affected, stifling hush of reverence that attends the Mountbatten funeral or the politicised lets pretend that is the Queens Speech to Parliament. At another, the agonising fixity of the grin as the minor sprigs of the Royal House do their turn on Its a Knockout. In between, the mock-seriousness and the frowning, stupid non-questions about non-subjects. Has Princess Diana grown up? Does Prince Charles know enough about architecture? Should the Queen abdicate? Is the monarchy too remote? Is it remote enough?

This symbiosis between the sacred and the profane and the noble and the vulgar is an embarrassing sign of underdevelopment. As a homage to antiquity and tradition it is a cringe-making failure. As an exercise in bread and circuses it is a flop. As the invisible cement to a system of supposedly well-ordered and historically-evolved democracy, it looks more and more like the smirk on the corpse. It has led to a most un-English impasse, where a Poujadiste female with ideas above her station has appropriated the regal We and many of Its prerogatives, and where a middlebrow Prince of the Blood mutters worriedly about the torn and worn fabric of society and its contract. Things are so distempered and out of joint, in fact, that sturdy democrats, even including a few born-again Monarchist-Leninists, are sighing for the piping times of the past.

Yet, if we ask how we got here from there, we will discover that the institution of monarchy, and the dull habits of mind that are inseparable from it, are themselves part of the difficulty. The monarchy may now be compromising with its own faint, puzzled, insipid impression of image and modernity, and looking foolish and undignified into the bargain. But the inescapable question do we need a monarchy in the first place or at all? has at last been asked. Let us try for a polite but firm reply.

The English have long been convinced that they are admired and envied by the rest of the world for their eccentricities alone. Many of these eccentricities red telephone boxes with heavy doors, unarmed policemen, courtesy in sporting matters are now more durable as touristic notions than as realities. But there is one special and distinctive feature of the island race which remains unaltered. Neither the English/British nor their foreign admirers and rivals know quite what the country is called.

Most nations, ancient and modern, have an agreed name. But we do not know whether this nation inhabits England, Britain, the British Isles, Albion or the UK. The only accurate nomenclature is the one that nobody employs the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. The words express the hope of a political and historical compromise rather than the actuality of one. If it were to read The United State of Great Britain and Northern Ireland it would provoke unfeeling mirth. And the United Republic would sound positively grotesque. No, it is the word kingdom that lends the tone. The British actually define their country and implicitly their society as, first and last, a monarchy.

This fact is so salient that people are apt to miss it. The ruling party forms Her Majestys Government and the opposition parties make up Her Majestys Loyal Opposition. The right people speak the Queens English (though mercifully few employ her tone). The Queens peace is kept, at least so far as the defence of the realm goes, by the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force and any number of royally-commissioned regiments. No letter or parcel may be sent without a royal endorsement in the form of a Queens head. The adjective royal is an automatic enhancer, with the Fleet Street usage right royal meaning anything that is extra or jolly good, most especially if it involves royal patronage or the royal warrant as in the bizarre, cumbersome re-naming of the Royal National Theatre.

Next page