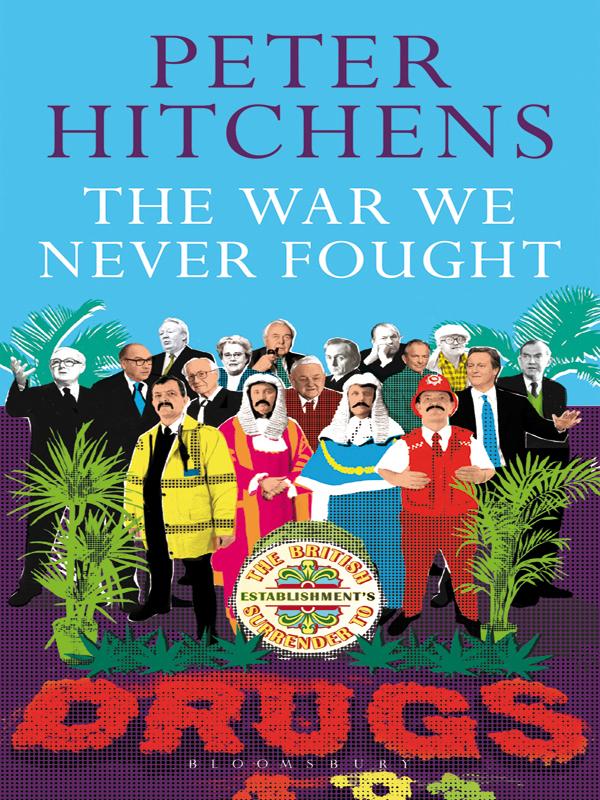

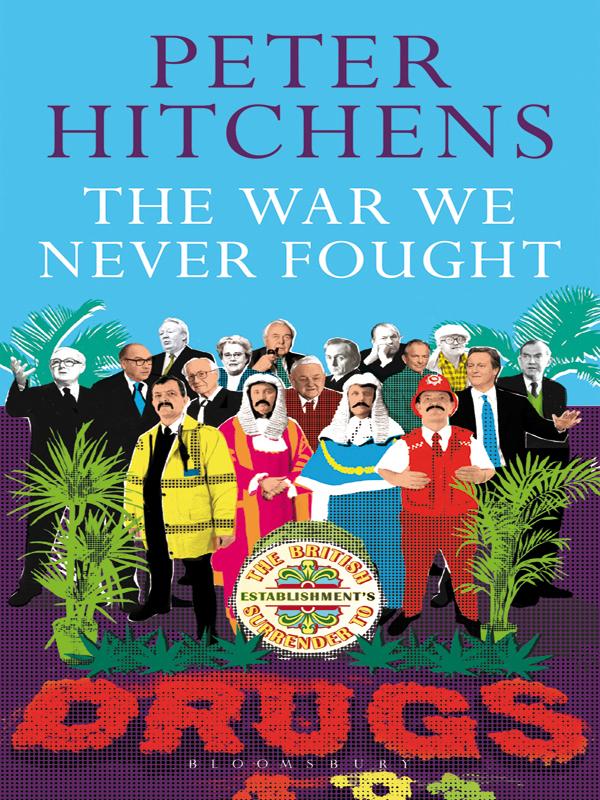

The War We Never Fought

The British Establishments Surrender to Drugs

Peter Hitchens

First published in Great Britain 2012

Peter Hitchens, 2012

The moral right of the author has been asserted

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the Publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. Every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright holders of material reproduced in this book, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the Publishers would be glad to hear from them.

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square

London WC1B 3DP

www.bloomsbury.com

Bloomsbury Publishing, London, Berlin, New York and Sydney

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-4411-7206-8

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Typeset by Fakenham Prepress Solutions, Fakenham, Norfolk NR21 8NN

Contents

Many people made me want to write this book, but they will not be very pleased to be given the credit for doing so. They are the legion of politicians, commentators, celebrities, ex-policemen, serving policemen, judges, lawyers and cultural figures who repeatedly insist that this country groans under the heel of an oppressive prohibition regime.

All of them ought to know better, and this book will enable them to know better. We shall then find out if their urgently-expressed opinions are based upon fact, or on some other foundation.

I owe a different sort of debt to Robin Baird-Smith, a superlative publisher who endures much when he has to, encourages when encouragement is needed, and listens when it matters most; to Peter Wright, Editor of the Mail on Sunday for most of the period during which I researched and wrote this book, who gave me freedom to pursue this subject, and provided essential support when it was not fashionable to do so, and most of the rest of Fleet Street was running the other way; To Kathy Gyngell of the Centre for Policy Studies, a valuable ally in the struggle against the liberalisers; to Mary Brett, whose unrelenting desire to protect the young from drugs with facts and logic deserves wider recognition; to the librarians at Associated Newspapers, friendly and helpful keepers of one of the most precious archives in the English language; to my elder son Daniel, who has now twice come to my rescue at a decisive moment in the making of a book, and to Nicola Rusk, who also played a major part in herding my prolix paragraphs into a coherent shape.

Above all, my thanks are due to my wife, Eve, from whom I must steal so much valuable time each time I set out to write a book, who must listen to my complaints and vows that I shall never again write a book (always broken) and who has to endure the reverses and difficulties without having the pleasures of scribbling.

They should share any credit. I take all the blame

For Eve

O n a secret site somewhere in Southern England, as you read these words, a major drug company is quite legally growing large quantities of cannabis. The essential ingredients of the plant, packaged as a mouth-spray, are available on prescription from the National Health Service. It is said, though the evidence is open to contention, to alleviate some of the symptoms of multiple sclerosis. Perhaps, in time, it will have other applications.

On another not-so-secret site, near where the Chiltern Hills run gently down towards the Thames Valley at the Goring Gap, the observant traveller may in most summers see large fields of regimented opium poppies blooming (in some years the fields are left fallow). These, too, are grown, harvested and processed under licences issued by Her Majestys Government. If they were not, the nearby Royal Air Force base at Benson might be required to destroy them from the sky. In this case the exotic and colourful harvest is used to produce medical morphine, ever more in demand for the sick and dying, who have benefited, or otherwise, from the ability of medical science to keep us alive against all odds, and the increasing desire of us all that the old should die out of sight, in vast remote hospitals.

Drugs and their relation to the law are a complicated subject. A crop that would bring down napalm upon an Afghan farmer is officially encouraged in Oxfordshire. Another crop, which the police would raid if it were in the loft of a suburban house, is providing officially sanctioned comfort to sufferers from a much-feared disease.

There is more. Each year, astonishing numbers of prescriptions are issued for drugs officially described as antidepressants. Many of these are given to men and women living in areas where unemployment is high, or suffering other social ills.

Perhaps most surprising of all to an alien visiting from the recent past (and who or what could be more alien than such a person?) is the increasing prescription, to children in Britain and the USA, of such drugs as Adderall and Ritalin one an amphetamine and the other with characteristics very similar to the amphetamines. These pills are supposed to improve the behaviour of children supposedly suffering from an ailment with no objectively measurable symptoms, called Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). They are also used to treat children who are said to be in the throes of Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD). I am not making this up.

Well, I have suffered, or in my view benefited, from Oppositional Defiant Disorder since I emerged screaming into the world, 60 years ago, surrounded by anxiously praying Maltese nuns. And I am haunted and dismayed by the idea that, had I been born into the present age, it would have occurred to more than one of the adult institutions in which I was Oppositional and Defiant to turn me into a conformist by classifying my discontents as a Disorder and prescribing me a little pill. This idea either nauseates you, or it does not. If it does not, then what follows is probably of little use to you.

Now, leaving all other considerations on this subject aside, I think it is important for our society to wonder why it has lately become so ready to accept that human woe can be cured or soothed by chemicals. These chemicals do not alter or reform the ills of our civilisation. They adapt the human being to them.

Later in this book you will find some interesting remarks made by Aldous Huxley, about the Brave New World of willing, even enthusiastic self-stupefaction which he feared we were embracing.

Having lived through the great moral, political and cultural convulsion that transformed my country and others between 1968 and today, I am struck by one great paradox. Most of us, as we cheered on the French students in Paris, or marched righteously against the Vietnam War, or expressed our scorn for the racial bigotry of our elders, or sought the end of puritan sexual rules, were united by one good bond. We loved liberty and hated tyranny. We were often, but not always, wrong about the causes we joined. But we were never apologists for serfdom and dull-witted, thoughtless contentment. If the world was awry, then we thought we should change it, not adapt ourselves to injustice and wrong.

Next page