P LAN OF H ITLER S B ANKER

P REFACE TO THE S EVENTH E DITION

It is now fifty years since I was appointed by the late Sir Dick White, then head of Counter-Intelligence in the British Zone of Germany, to find out, if possible, what had happened to Hitler, who, by that time, had been missing for over four months. I carried out my task and made my report to the Four Power Intelligence Committee in Berlin on 1 November 1945. That report, which is sometimes cited as The British Intelligence Report on the Death of Hitler, completed my official duty. Afterwards, when I had been demobilized, Sir Dick White persuaded me to write this book, which was first published in March 1947. I then dedicated it to him. I now dedicate it to his memory, as its only begetter, and my constant friend.

After fifty years a book which has never been out of print may celebrate a modest jubilee, and in this preface I shall give a brief account of its fortune over those years. I have already said something of this in the introductory chapter, which began as the introduction to the third edition; but even that chapter was written nearly forty years ago, when the events of 1945 were still fresh in memory. Now, for most readers, they have sunk into history; so I can look back on the matter from a more distant perspective and take a somewhat longer view.

The immediate problem which faced me in 1945 was the personal fate of Hitler. That was my brief, and I kept to it. But in addition to this first problem, the German problem, there was also a second problem which, though distinct, could not be entirely disentangled from it, which dogged me throughout my inquiry, and which remained unsolved for several years thereafter. This was the Russian problem. For how was it possible, I asked myself, that the Russians, who had captured Berlin and occupied the ruins of Hitlers Chancellery, could have failed, or omitted, to establish the facts about Hitlers fate? They had the opportunity, and the means, perhaps the duty, to do so, and yet in September 1945 they were expressing complete ignorance, and thereby spreading the confusion, the speculation and the suspicion which I was called upon to dissipate.

Since it was no part of my brief to unravel this second mystery, I did not, during my inquiry, address myself to it. But I could not fail to notice the paradox implicit in the situation. For while the Russian authorities professed their own inability to solve the problem of Hitlers fate, they showed no desire to see it solved by others. They neither sought evidence from us nor answered our legitimate questions. They seemed totally uninterested and avoided all discussion of the subject. When I made my report, the Russian general present, when invited to comment, replied laconically, and in a toneless voice, Very interesting. All this seemed odd to me; but as the Russians were our allies, we had to respect their foibles, to which, by that time, we had become accustomed.

The solution to this Russian problem came in 1955, when Nikita Khrushchev liberated the German prisoners of war held in Russia and sent them home. By questioning them I was able to establish the facts and dealt with them fully in the new introduction to the third edition of my book. That introduction has been an integral part of the book ever since, and I need not repeat its contents here.

Thus by 1956 both the German and the Russian problems concerning the death of Hitler had been solved; but each of them had left behind it certain residual problems of which I felt obliged to take notice in annexes prefaces or appendices to successive editions of my book. In this edition I have decided to eliminate all such annexes. Progress reports in on-going controversies, they have become otiose in so far as those controversies are resolved. It will be enough if I now resume them, in a more summary manner, and deal with them together.

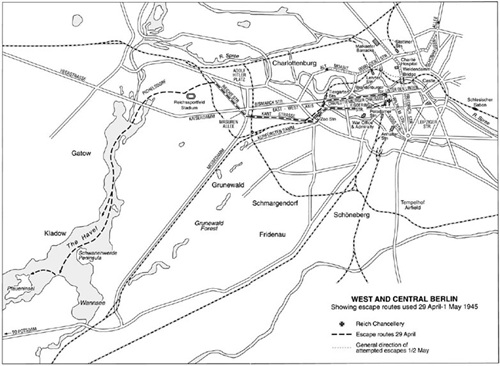

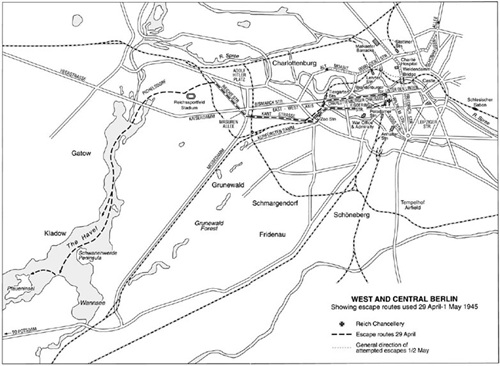

The residue of the German problem concerned the fate of Martin Bormann, who had also disappeared during the fall of Berlin. What had happened to him? My inquiry had satisfied me that he had been in Berlin to the end, and that he had intended to survive. He had proposed to make his way to the West and to offer the benefit of his advice to the successor appointed by Hitler, Admiral Doenitz, who was then in Ploen, on the Danish border. I knew that he had left the Bunker alive, but had never reached his destination. One witness, Artur Axmann, Reich Youth Leader, claimed, very circumstantially, to have seen his dead body in Berlin, but since his statement was uncorroborated, I could give it only provisional acceptance. So the question was left open.

This uncertainty lit a long train of fanciful theories, which have spluttered intermittently for fifty years. In 1965 a licensed Soviet journalist, Lev Bezymenski, dutifully published evidence that Bormann had escaped to South America to serve US imperialism in the Cold War. In fact his own work was itself an exercise in that war, though a very weak one: correctly interpreted, his alleged evidence showed not that Bormann was moving from Germany to South America but that his office was being moved from Berlin to Tyrol. However, the South American thesis was kept going for another decade. Its last champion was an American writer, Ladislas Farago, an enterprising but rather trustful man. After following an apparently hot trail through that large continent, he claimed to have run Bormann to ground in the hospital of a Redemptorist convent in Bolivia, and there to have listened to his dying words, issuing faintly from the bedsheets. After that, the South American thesis died too: it had overreached itself. It had also been overtaken by another.

This rival thesis placed Bormann, surprisingly, in Russia. The idea was not entirely new vague hints of it had been uttered since 1945 but in the autumn of 1971, while Mr Farago was pursuing his quarry in Argentina, it was formally launched, with a more explosive content, in Germany. Its proponent was a man of authority in such matters and some importance in the country: General Reinhardt Gehlen.

During the war, Gehlen had been the Abwehr officer who directed military espionage on the Russian front. Afterwards, thanks to this useful experience, the patronage of Dr Adenauer, and the beginning of the Cold War, he had become head of the new West German intelligence service, the Bundesnachrichtendienst. Now, in his memoirs, breaking (as he put it) a long silence, he revealed that, during the war, he and his chief, Admiral Canaris, had independently come to the conclusion that Bormann, from the beginning of the war against Russia, had been a Soviet spy in Hitlers headquarters, regularly supplying the enemy with vital strategic intelligence and thereby contributing to the German defeat; and he added that, more recently, he had discovered the sequel to the story: in 1945, as a reward for his services, Bormann had sought and found protection in Moscow, where he had occasionally been seen by reliable witnesses and had recently died.

For this interesting theory Gehlen did not state his sources, explaining that they too needed protection. Consequently, it was brushed aside by his critics and enemies, who were not few. Moreover, only a year later, it was effectively refuted when two human skeletons, which had been dug up in waste ground near the Lehrter Station in West Berlin i.e. not far from the place where Axmann claimed to have seen the bodies were forensically examined and identified as those of Bormann and his companion in flight, Dr Stumpfegger. On this evidence, the legal case against Bormann as a major war criminal, which had remained open since 1945, was formally closed. The mystery, it was said, had now been solved and the hunt, after twenty-seven years, could be called off. This was the position in 1978 when I last took notice of the matter in the fifth edition of this book; and I saw no reason to add any further comment in the next edition, published in 1982.

Next page