One Small War

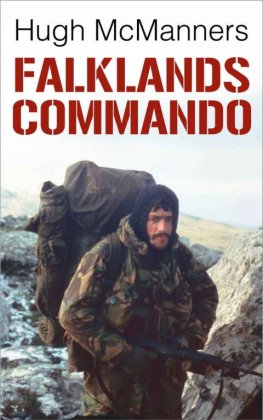

It was a whilebefore anyone realized that the guns had stopped firing (writes PatrickBishop). Wewere standing on a rock ledge on the east face of Mount Harriet lookingdown towards the town. The crags around were chipped andsmashed by the fighting of the last two days and the pathetic debris ofthe Argentinian defenders lay strewn all around. At threeoclock there were some uncertain cheers from the Marines on the rocksabove. Thats it, one of themshouted. Theyve surrendered. One of the officers, Major Mike Norman,who had been captured and sent back toEngland by the Argentine invaders ten weeks before, laughed and shookhands with an officer standing next to him, but the rest of uswanted the news to be true too badly to rejoice until we were sure.

The commanding officer, Colonel Vaux, went over to the radio and called up Brigade.Its not confirmed, he said. Its just something they got from fleet. It started to snowagain. Colonel Vaux went back to the radio. Theyre falling back from Sapper Hill! he said. There arewhite arm bands and flags all over the place.

The same news was travellingfast across the battlefield. The Welsh Guards scarcely hadtime to take it in before being ordered forward to Sapper Hill, thelast Argentine stronghold before Port Stanley (writes John Witherow).Tired soldiersstaggered out of their bashers pulling kit intorucksacks and piled into Sea King and Wessexhelicopters to be ferried the last few kilometres to the foot of thehill. Inside the aircraft the soldiers gave each other nervousgrins. The elation at the news that the Argentinians were retreatinghad been replaced by uncertainty as to whether they were flyingto witness a surrender or to fight the final battle. The helicoptersshuddered to the ground by a jagged outcrop of rock on anunmetalled road running by the side of Mount William. The men jumpedout and scrambled into the heather looking for cover. Therewere no Argentinians in view. Get back on the road, those surroundsare mined, shouted an officer.

The menreturned to the track and set off towards the outline of Sapper Hill.Their faceswere dark with camouflage cream and tiredness but the pace as theywalked got faster and faster. The intelligence officer, CaptainPiers Minoprio, was called to the radio. Theres a white flag overStanley, he shouted. We were trotting downthe road now, passing soldiers struggling along with enormous packs andheavy machine guns. The order came down the line toclose up and unfix bayonets. The defenders abandoned possessionslittered the sides of the road:kit bags, blankets and helmets. Mud-stained comic books and lettersfrom home skipped about in the wind. We passed an artilleryposition still smoking from the battering it had received from theBritish guns. The ground around it was churned up like a newlyploughed field. Two Marines were lying by the side of the road. One hada dark red patch spreading across his trouser leg and theother had a bloody blotch on his head. Medical orderlies were hunchedover them murmuring reassurance. We climbed on to a Scorpiontank and caught up with the forward Commandos who were skirting thebase of Sapper Hill. They had been fired on by the retreatingArgentinians as they ran out of their helicopter and there had been afirefight that lasted twenty minutes. It was probably the lastskirmish of the war.

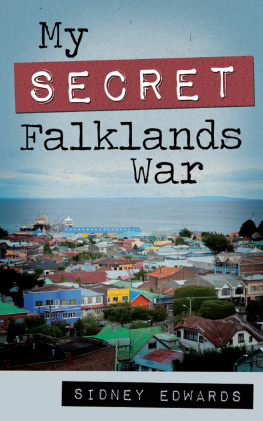

We rounded the bend and came within sight of Stanley. An Argentine corpse was lying face down in the middle ofthe road. The soldiers peered at the body, full of curiosity. Spread out lads! shouted one of the NCOs. Takecare, this is too easy. The troops moved up the muddy path onto Sapper Hill, scouring the ground in frontof their feet for signs of mines. We knew the name of the hill wellfrom numerous intelligence briefings and it had been theGuards objective in the renewed assault due to take place that night,but now the machine gun positions and trenches wereempty. A vehicle lay abandoned at the side of the road and there wereration tins and biscuits trodden into the mud around thedug-outs. The only sound was the wind and the tramp of boots. Downbelow in Stanley, smoke swirled away from shelled houses. TheArgentine soldiers stood by their dug-outs staring at the approachingtroops. The capital looked suburban and insubstantial in the waterylight, a smattering of green-and red-roofed houses. The large red crosson the roof of the hospital stood out in the middle of thetown. A white helicopter buzzed across the bay carrying casualties tothe Argentine hospital ship BahiaParaiso .The Welsh Guards commanding officer, Lt.-Col Johnny Rickett, stood onthe crest of the hill taking a swigfrom a whisky bottle that was passing among the officers. BrigadierTony Wilson, the commander of the 5th Infantry Brigade, joinedhim looking down on the town. It seems an incredibly long way to comefor this, he said.

The troops weretold to wait outside Stanley while negotiations were started for asurrender, so we both decided to go in ahead of them. We stripped offour camouflage kit, piling it next to one of the 155mm guns thathad been shelling us the night before, and started to walk the lasthalf mile into town. It was difficult to know what attitude tostrike with the Argentine soldiers who sat by the road in trenchespointing their guns towards us. We tried to be as ostentatiouslyharmless as possible, waving and calling greetings, but there was noresponse and it was hard to stop speculating about how it mightfeel to be struck by a bullet. As we reached a cattle-grid on the edgeof town three Argentine conscripts approached. They wereunarmed and grinning and insisted on shaking our hands. For the firsttime we felt that the battle for the Falklands was all butover.

The speed ofthe Argentinian collapse that Monday morning astounded everybody. TheBritishhad been appealing to them to surrender for four days without receivingany sign that they were prepared to do so and most of thesoldiers were expecting to fight through Stanley street by street. As the news of the surrender came through,the commander of the land forces on the Falkland Islands, Maj.-Gen. Jeremy Moore, had ordered an air raid on Sapper Hill toblast the Argentinians with cluster bombs. I heard on the radio that the Argentine soldiers were all walking about and I hada Harrier strike due to go in, he said. I grabbed the radio myself and did all the talking for the next two hours. Thestrike was due within minutes and if it had gone ahead it may have meant the whole war continuing.

Considering thewar ended in a reasonably neat and satisfying way for Britain it iseasy toforget that it began in muddle and semi-farce. The slide into conflictstarted on 18 March 1982, when Constantino Davidoff, a GreekArgentine scrap metal merchant with a contract to dismember an oldwhaling station on South Georgia ran up the blue and whiteArgentinian flag to remind the world of Argentinas claim to theterritory, which had been acquired by Britain at thebeginning of the century. It took time for the consequences of thissmall coup de thtre todevelop. When diplomatic representations met with calculatedindifference in Buenos Aires it became clear that Davidoffsaction was a deliberate test of Britains will. Up until then thedispute over the ownership of the Falklands had, in the eyesof Britain at least, shown a capacity to be stretched, painlessly, intoinfinity. But on 2 April, a day late it was said to exploitthe full irony of the situation, Argentina invaded the Falklands,expelled the British garrison of Royal Marines and declared themthe Islas Malvinas. Britain reacted first with indignation and thenwith force.