CONTENTS

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

The objective of this book is primarily to give the reader insights, alternative answers and in some cases the truth relating to certain events that took place during the Falkland Island War of 1982. In addition its content is aimed to broaden ones knowledge of a very small number of Armed Forces personnel employed in specialist duties during the period 19401990, who, because of the restraints placed on them by their signing of the Official Secrets Act, have seldom attracted the attention of the general public. I have deliberately liberally peppered my real war memories with an overview of my military career in general during the period 19551988, in order to give the reader an insight into an aspect of Army life that seldom hits the headlines.

After 1990, mainly because of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and the more relaxed relations between the super powers after the Cold War, the role of these specialist personnel changed and through these changes, and more open reporting by the media, their existence has become more widely known. My specialist knowledge and expertise only came about after years of experience employed in the clandestine world of the electronic intercept of communication systems used by the potential enemies of Great Britain and her closest allies.

The specialists to whom I refer were actively employed 365 days a year. When on operational assignments their place of work was often hostile and on occasions very dangerous; they could be employed in the air, on the ground or at sea. Where they worked was also varied; they could be deployed to any continent in conditions, from the opulent and palatial to living and working in chicken coops, as they once did in Kenya.

Classified information pertaining to Official Intelligence Activities in all its forms and Signals Intelligence in particular, is not subject to any fixed timetables for release, such as the so-called Defence Notice (D Notice) or since 1971 its replacement the Defence Advisory Notice (DA Notice) and the 30-Year Rule. The D Notice was established in 1912, bolstered by the Official Secrets Acts, to define subjects that are not cleared for public broadcast. With the progress of technology, todays DA Notices cover media broadcast content via radio, films, television and the internet, and may be applicable to other government information under the Public Records Acts. In addition, the Freedom of Information Acts do not apply to the intelligence agencies; the Acts explicitly exempt them from any obligation to provide information concerning any units of the Armed Forces which are for the time being required to assist the Government Communications Headquarters [GCHQ] in the exercise of its functions.

In February 2010, the British Government presented their Review of the 30-Year Rule to Parliament and the general public. Amendments to the Constitutional Reform and Governance Bill were tabled.

The reduction of the 30-Year Rule through amendments to the Constitutional Reform and Governance Bill is perhaps one of the first steps towards transparency in the field of dissemination of past highly classified information into the public arena. No sooner had the ink dried on this Bill now an Act when in June 2010, details of the 1946 UKUSA (pronounced ew-koo-sa) Secret Agreement was released to the British National Archives by GCHQ. This agreement, brokered with the US, led to the sharing of all signals secret intelligence between the two countries. The agreement was later extended to include the three former British dominions, Canada (1948), Australia and New Zealand (1956). The UKUSA Agreement was a follow-up to the 1943 BRUSA Agreement, a Second World War agreement on cooperation over intelligence matters this was a secret treaty, allegedly so secret that it was kept from the Australian prime ministers until 1973 and formalised the intelligence sharing agreement in the Atlantic Charter, signed in 1941, before the entry of the US into the conflict. While rumours suggesting the existence of such an agreement had persisted for many years, outside of GCHQ the actual document, or its content, has never been published before. The agreement itself states It will be contrary to this agreement to reveal its existence to any third party whatever. With top secret codeword protection, the document was drawn up and signed by members of the forerunners of the National Security Agency (NSA) and GCHQ, the State-Army-Navy Communications Intelligence Board, known as STANCIB, and the London Signal Intelligence Board.

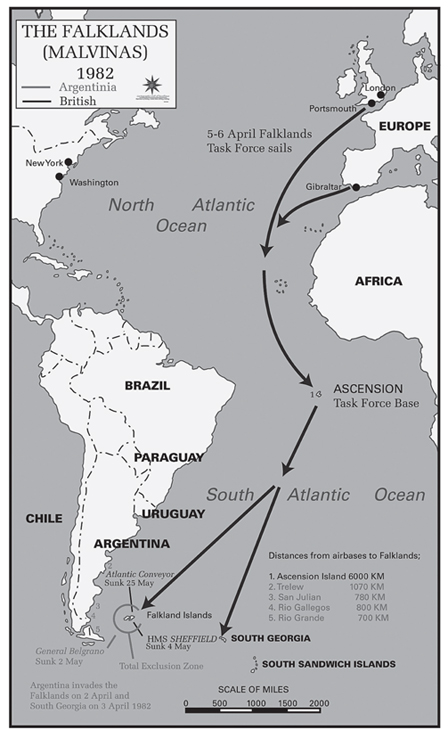

The Silent Listener confirms the existence and role of the Special Task Detachment during Operation Corporate and provides, for the first time in the history of British warfare, details of the deployment and operational role of a dedicated, but limited, ground-based electronic warfare weapons facility under the direct control of the Land Force Commander; a significant development in military history that appears to have been omitted by Professor Lawrence Freedman in his Official History of the Falkland War.

The content of The Silent Listener has been shown to and commented on by authorities at both Government Communication Headquarters and the Ministry of Defence; in consequence all requests from these Government Departments for changes to meet the terms of the Official Secrets Acts have been complied with. Failure to have done so may have caused damage to Great Britains strategic and tactical military capability and aims, and risked British servicemens and womens lives in current and future conflict.

The Constitutional Reform and Governance Act means that over the next 10 years national archiving after 20 instead of 30 years will be required by law. Though within the Act, in Freedom of Information 46 (2) it states: The Secretary of State may by order make transitional, transitory or saving provision in connection with the coming into force of paragraph 4 of Schedule 7 (which reduces from 30 years to 20 years the period at the end of which a record becomes a historical record for the purposes of Part 6 of the Freedom of Information Act 2000).

The art of intelligence gathering has been practised almost since the beginning of human societies. The need of individuals, organisations and nations to know more about others than the others know about them is insatiable. The ways and means of gathering intelligence are vast and varied, as are the reasons why groups feel the need to gather such information.

Throughout history much has been written about the world of intelligence gathering on a national level, where the target array varies from the activities of an entire nation, down to the individual on the street gossiping over the garden fence. While some people, through the press and other forms of media, like to feel they know a little about the nations civilian intelligence gathering organisations such as MI5, MI6 and perhaps the Government Communications Headquarters, it is generally only those, because of security implications and the policy of need to know, who have been employed or actively involved in the various aspects of military intelligence that have any real knowledge of the role and capabilities of the Intelligence Corps and in particular that element whose specialist duties are in the collection, transcription, translation, cryptanalysis and eventual reporting of signals intelligence. In the twenty-first century it has more commonly become known as electronic warfare.

Next page