Revelatory history at its best. STEPHEN FITZGERALD

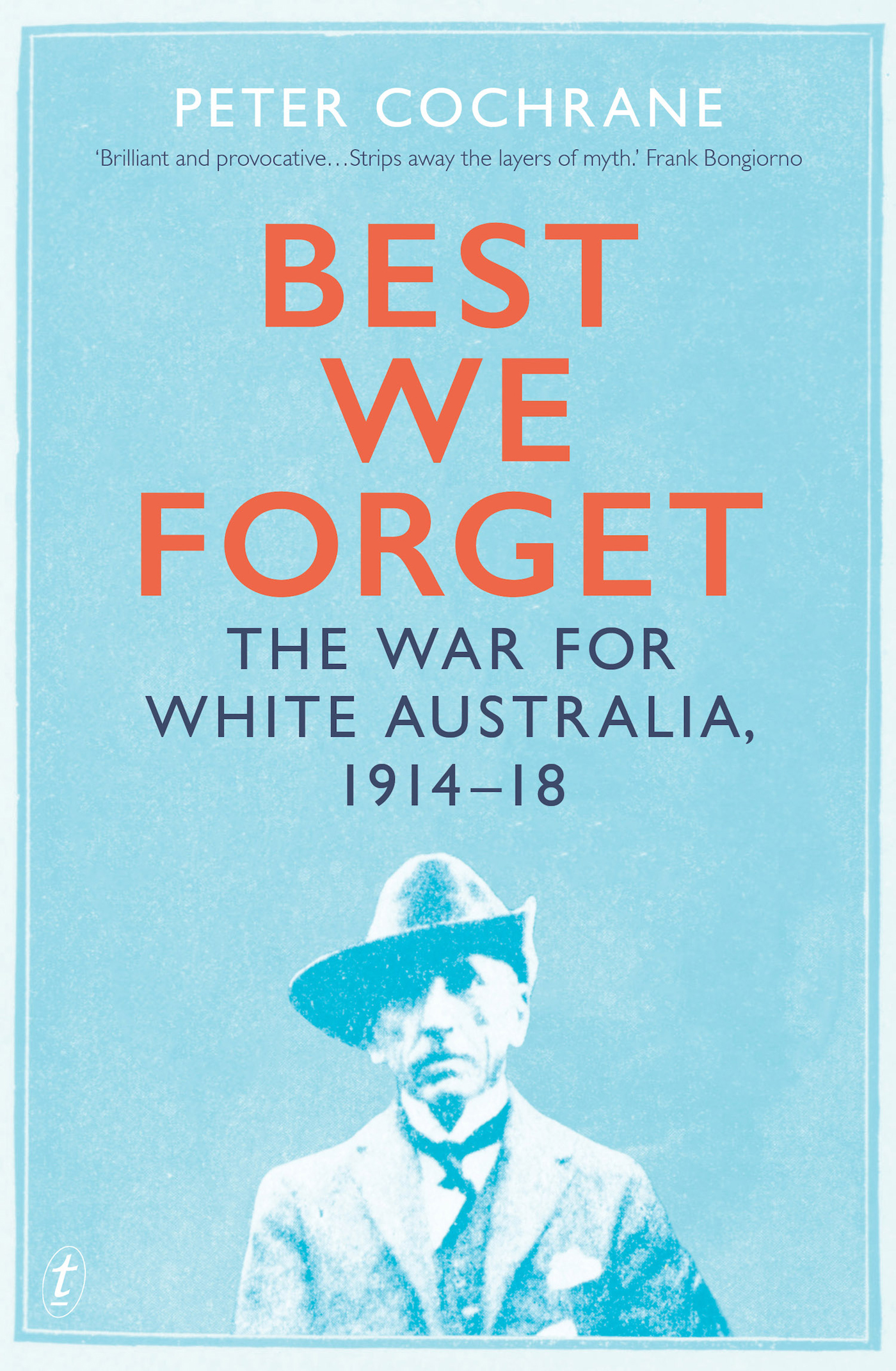

IN THE HALF-CENTURY PRECEDING THE GREAT WAR there was a dramatic shift in the mindset of Australias political leaders, from a profound sense of safety in the empires embrace to a deep anxiety about abandonment by Britain.

Collective memory now recalls a rallying to the cause in 1914, a total identification with British interests and the need to defeat Germany. But there is an underside to this story: the belief that the newly federated nations security, and its race purity, must be bought with blood.

Before the war Commonwealth governments were concerned not with enemies in Europe but with perils in the Pacific. Fearful of an awakening Asia and worried by opposition to the White Australia policy, they prepared for defence against Japan-only to find themselves fighting for the empire on the other side of the world. Prime Minister Billy Hughes spoke of this paradox in 1916, urging his countrymen: I bid you go and fight for White Australia in France.

In this vital and illuminating book, Peter Cochrane examines how the racial preoccupations that shaped Australias preparation for and commitment to the war have been lost to popular memory.

A great read[It] will seep into the national consciousness. TIM WATTS

Contents

In memory of

John Hirst

In human affairs there is never a single narrative. There is always one counter-story, and usually several, and in a democracy you will probably get to hear them.

INGA CLENDINNEN

The History Question: Who Owns the Past?

Quarterly Essay 23, 2006

I bid you go and fight for White Australia in France. Billy Hughes, Sydney Morning Herald, 27 October 1916

For much of the nineteenth century, white Australians were untroubled by the outside world. Asia was considered too poor and backward, or too downtrodden, to threaten the Australian land mass. And Europe was thought to be too far away to visit its dismal ructions on the colonies. Isolation was insulation.

That benign situation did not endure. From the 1870s onwards, the strategic setting deteriorated, the outside world seemed to crowd in and white Australians felt ever more vulnerable to threats from abroad. Political leaders in the Australian colonies were disturbed by the gathering tensions in international relations: the arms race in Europe; the scramble for colonies; the Russian navy in the North Pacific; and the movement of Germany and France into the South Pacific, into New Guinea and the New Hebrides respectively.

An awakening Asia was also a source of bourgeoning anxiety. Concerns over Chinese migration, the threat to jobs, to culture and racial purity, reached a pitch in the last quarter of the nineteenth century; while the rise of Britains protg, Japan, its navy cruising the Pacific in the 1890s, was viewed as a troubling development for the security of the Australian land mass.

Worst of all, the experience in these decades proved, incontrovertibly to some, that Britain could not be relied uponthat Londons priorities were elsewhere, the British navy stretched thin, and Australia could well be alone come the day of reckoning. In this context, in the old century and the new, were planted the seeds of the young nations wholesale commitment to the anticipated world war.

Across the half-century preceding the war of 191418 the transition was dramatic: shifting from complacency to alarmism, from a profound sense of security in the embrace of empire and the protective reach of the Royal Navy to a deep anxiety about the possibility of abandonment, even betrayal, should the day of reckoning arrive.

Collective memory may now recall a spontaneous rallying to the British cause in 1914, the assumption of near total identification with British interests and the good, strategic reasons why Australians did not want Germany to defeat Britain and thus destroy the fabric of the Empire upon which we rest, as Prime Minister Billy Hughes put it.

But history, meaning some of the best scholarship in the field, suggests an underside to this storya long and tortuous lead-up; an agonising recognition on the part of Australias leaders that security, and most importantly race purity, must be bought with Australian blood; and a concern, not with enemies in Europe or the Middle East, but with imminent or latent perils in the Pacific, meaning Japan.

Thus, for almost a decade prior to 1914, a succession of Commonwealth governments directed their energies to preparing for defence against Japan, only to find themselves fighting for the empire in Turkey, Palestine, France and Belgium. In the midst of the war Billy Hughes spoke plainly of this paradox: I bid you go and fight for White Australia in France, he told the men of Australia in 1916.

Why have the racial preoccupations that shaped Australias preparation for and subsequent commitment to war been lost to memory? Why has the obsession with the Pacific and race purity, with Japan in particularan obsession stretching from colonial times to the Paris Peace Conference of 191920 and beyondescaped recall? Why has the racial dimension of the strategic thinking of Australias leaders been lost to posterity? Why does our collective remembrance contain not the faintest notion that the nations war was, in no small part, a war for white Australia? In chapters to follow I spell out the racial context, and the racial dimensions of the war itself, concluding with a chapter on the politics of popular memory: how and why the substantial literature on this subject has been shunned.

This is the last land open to the white manthe only one that can be purely British.

C. E. W. Bean, 1907

Every generation moulds the Anzac Legend according to its own ideals, and thus moves further away from the original, further away from the understandings that the legend embodied in its first iteration, the ideals it endorsed and the values it represented.

The legend we know today is nothing like the one that evolved in the First World War and the 1920s.

In its formative years, and for years thereafter, the Anzac Legend was a rite-of-passage story about the foundation of a nation. It was also a celebration of Australias part in the war in terms of a racial triumph, a triumph which affirmed the qualities of Anglo-Saxondom, of the British race and what C. J. Dennis called the Southern breedthe offshoot of the British race that occupied Australia.

We see this racial essence in the thinking and writing of C. E. W. (Charles) Bean, the man who did more than any other to establish the legend. The beginnings of the national story that Bean would shape in his wartime journalism, and subsequently his Official History of the war and other books, can be found in his pre-war writings. He had the template long before a shot was fired. This is not mysterious, for the racial legend that he and others moulded was the pinnacle of half a century of meditations on race and anxious musings on the struggle for racial survival.

Seeds of a Legend

In his pre-war journalism for the Sydney Morning Herald, and in several books, Beans focus on national character is clearly evident, as is his belief that national character in the colonies was evolving a superior being, an improved strain of the British bloodline. The true Australian native, he wrote, is not a black man[nor] an Englishman but a new man hammered out of the old stock. Bean described this new man as a tall, spare man, clean and wiry rather than muscular, and in his face he saw a certain refined, ascetic strength.

Next page