Acknowledgements

I wish to record my thanks to the Australian Prime Ministers Centre, Canberra, for granting me a fellowship in 2009 and to Kings College London for the study leave which made the research for this book possible. I am also grateful to my friends and colleagues, Scott Bennett, Frank Bongiorno, John Connor, Michael Cook, David Lee, Richard Murison and Kerry Sanderson, for their comments on early drafts, and to seminars at the APMC and at the Menzies Centre for Australian Studies, Kings College London, for constructive criticism. My children, Andrew, Wendy and Harry, were, as ever, a constant source of encouragement and strength, and I dedicate this work to them.

Carl Bridge

London

July 2010

Introduction

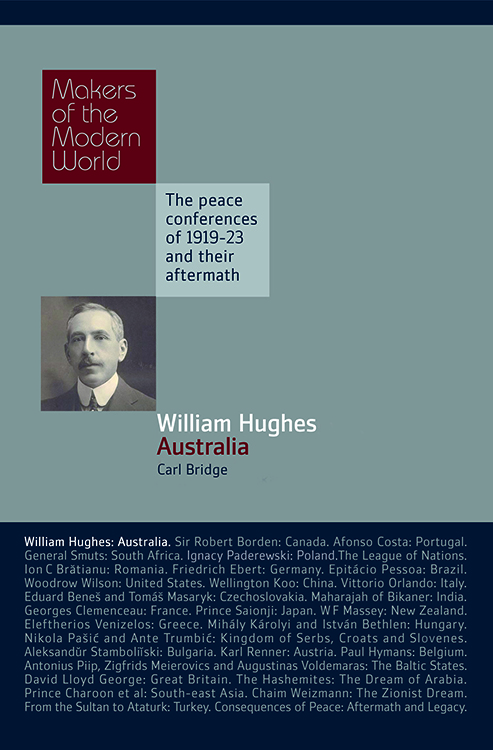

The most recent biographies of William Morris Billy Hughes, Australias Prime Minister during the turbulent days of the First World War, are now 30 years old. One is an essay on his rhetoric; one a study of how he worked the Labor Party and trades union machines; and the third, his authorised biography, is comprehensive and an excellent piece of work but now dated. It is more than time for a re-appraisal of the career of Billy Hughes.

My study aims to set Hughes firmly in his wider context, as a prominent figure in the far-flung British diaspora that characterised the British Empire at its height, the phenomenon historians are now describing as the British World. It will show how Hughes operated as a quintessentially independent Australian Briton of his time. In order to do so, it will link the local, national and international dimensions of his activities and demonstrate the ways in which each influenced indeed, at key moments, leveraged the others. Hughess enemies demonised him as a Labor rat who betrayed his party; his friends saw him as the Little Digger who was his countrys political saviour during its greatest crisis. His finest hour was at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, when, as Australias representative, he defied the odds to secure vital concessions for his country and Empire. He was arguably Australias most significant politician of the 20th century and an Imperial figure of the first rank.

New South Welshman, 18621901

Like his illustrious British contemporary, David Lloyd George, William Morris Hughes was a Welshman who happened to be born in England, in his case in London; unlike Lloyd George, Hughes made his career as a New South Welshman, as an Australian Briton. Born on 25 September 1862 in the London working-class suburb of Pimlico, which acted as a buffer between moneyed Belgravia and the Devils Acre and other Westminster slums, William, Little Willy, Will or Billy as he became known, was the only child of a Welsh-speaking carpenter and his English-speaking Welsh wife. His father, who was originally from Holyhead in Anglesey, north Wales, worked maintaining the Houses of Parliament, was a deacon in his local Particular Baptist Church, and a pillar of respectable working class Toryism. His mother, who was Anglican, worked in service. Her family had for generations owned and worked a small farm at Llansantffraid, also in north Wales just 3 miles across the border with England. Hughes was thus a cultural hybrid, truly British: a Cockney Welshman, relatively anglicised and the result of two internal migrations from the Welsh countryside to the English and Imperial metropolis.

Will Hughes spent his first 22 years in state schools in inner London and on the north Welsh borders. His mother died when he was six years old and he went to live with his fathers sister who ran a substantial boarding house in the Welsh holiday town of Llandudno, where he attended the local grammar school. Here he was taught well in English but also picked up a smattering of colloquial Welsh. Despite his small frame (he grew to a very spare, though wiry, 5 feet 5 inches) and chronic dyspepsia, which bedevilled him all his life, he became a good sportsman as a runner and with his fists, and a champion at marbles.

Aged nearly 12, Will moved back to London and attended St Stephens Grammar School in Pimlico, where two years later he became a pupil teacher for five years. There he was inspired by the great Liberal intellectual Matthew Arnold, who inspected the school and presented him with a prize of the complete works of Shakespeare, probably for his ability at reading aloud. Perhaps it was also Arnold who later inspired in him the ideal that an enlightened elite should govern the state for the benefit of all. But among the most important skills learned there would have been how to keep the attention of very large classes of potentially unruly pupils.

When he finished his apprenticeship and could afford it, he joined a volunteer battalion of the Royal Fusiliers. Unable or unwilling to secure a permanent teaching post, shunning the offer of a clerks stool in Coutts Bank and lured by adventure, he and a friend took advantage of one of the great, readily accessible human highways of the British world and migrated to Queensland on a colonial government-assisted passage in October 1884.

The Australia to which Hughes emigrated the six separate Australian colonies of New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia, Western Australia, Tasmania and Queensland was one of a number of neo-Britains, countries of British settlement spread across the globe, alongside Canada, Newfoundland and New Zealand. These were thrusting, raw, new frontier societies, with a preponderance of men and youth, politically advanced and liberal, yet parts of Greater Britain none the less. Among them, the Australian colonies first introduced the secret ballot, male then universal suffrage, payment of MPs, secular, compulsory and free primary education, industrial arbitration, an eight-hour day for skilled workers, and the worlds first Labor government. All this occurred a generation and more in advance of the Mother Country.

The colonists across the diaspora saw themselves as building modern and better Britains. The telephone, tramway, bicycle and electric light arrived in Australia in the 1880s. Marvellous Melbourne, built on the foundations of the mid-century gold rushes, saw itself as the second city of the Empire after London. The Australian economy rode on the sheeps back (wool being the principal export); but beef, wheat and minerals (gold, copper, silver, lead and zinc) were also significant. The limits of agrarian settlement had been reached in the 1870s in most colonies but California-style irrigation schemes were promising more intensive farming along the rivers. The infrastructure was growing apace; and with the railway and telegraph, the mighty bush was tethered to the world. In 1875 there were only 1,000 miles of track and by 1891 there were 10,000. An era ended in 1880 when Ned Kelly, the last great bushranger or outlaw, was captured at Glenrowan in rural Victoria with the aid of the steam train and the electric telegraph. A year earlier, the first cargo of frozen beef had been shipped from Sydney to London on the Strathleven. The era of the Imperial breakfast table had arrived.

The Australian population was 2.25 million in 1881, with a third living in towns and cities and fuelling a building boom. Literacy was virtually universal and women had been admitted to the University of Adelaide. Judged by meat consumption, Australians at that time had the highest standard of living in the world. The visiting British Fabian socialist, Beatrice Webb, remarked on the colonials vulgarity and a rather gross materialism An Australian Natives Association, for white colonists, had been formed in 1871 and, to mark their Australian-ness, they celebrated Wattle Day, when the first native flowers bloomed after winter, and used three Aboriginal cooees, or bush calls, instead of three cheers at meetings. The Heidelberg School of Australian Impressionists, among whose leading lights were Tom Roberts, Frederick McCubbin, Arthur Streeton and Charles Conder, were about to paint authentic Australian landscapes; and a distinctive Australian literature was about to emerge featuring the bush authors Henry Lawson, Banjo Paterson, Steele Rudd and Joseph Furphy. An Australian XI won the first Ashes cricket series against England in 1882, beating the English at their own game.