Youd have to be crazy to get yourself committed to a mental hospital.

T he story that follows is true. It is also not true.

This is patient #5213s first hospitalization. His name is David Lurie. He is a thirty-nine-year-old advertising copywriter, married with two children, and he hears voices.

The psychiatrist opens the intake interview with some orienting questions: What is your name? Where are you? What is the date? Who is the president?

He answers all four questions correctly: David Lurie, Haverford State Hospital, February 6, 1969, Richard Nixon.

Then the psychiatrist asks about the voices.

The patient tells him that they say, Its empty. Nothing inside. Its hollow. It makes an empty noise.

Do you recognize the voices? the psychiatrist asks.

No.

Are they male or female voices?

They are always male.

And do you hear them now?

No.

Do you think they are real?

No, Im sure theyre not. But I cant stop them.

The discussion moves on to life beyond the voices. The doctor and patient speak about Luries latent feelings of paranoia, of dissatisfaction, of feeling somehow less than his peers. They discuss his childhood as a son of two devout Orthodox Jews and his once intense relationship with his mother that had cooled over time; they speak about his marital issues and his struggle to temper rages that are sometimes directed at his children. The interview continues on in this manner for thirty minutes, at which time the psychiatrist has gathered nearly two pages of notes.

The psychiatrist admits him with the diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective type.

But theres a problem. David Lurie doesnt hear voices. Hes not an advertising copywriter, and his last name isnt Lurie. In fact, David Lurie doesnt exist.

The womans name doesnt matter. Just picture anyone you know and love. Shes in her mid-twenties when her world begins to crumble. She cant concentrate at work, stops sleeping, grows uneasy in crowds, and then retreats to her apartment, where she sees and hears things that arent theredisembodied voices that make her paranoid, frightened, and angry. She paces around her apartment until she feels as if she might burst open. So she leaves her house and wanders around the crowded city streets trying to avoid the burning stares of the passersby.

Her familys worry grows. They take her in but she runs away from them, convinced they are part of some elaborate conspiracy to destroy her. They take her to a hospital, where she grows increasingly disconnected from reality. She is restrained and sedated by the weary staff. She begins to have fitsher arms flailing and her body shaking, leaving the doctors dumbstruck, without answers. They increase her doses of antipsychotic medications. Medical test after medical test reveals nothing. She grows more psychotic and violent. Days turn into weeks. Then she deflates like a pricked balloon, suddenly flattened. She loses her ability to read, to write, and eventually she stops talking, spending hours blankly staring at a television screen. Sometimes she grows agitated and her legs dance in crooked spasms. The hospital decides that it can no longer handle her, marking her medical records with the words TRANSFER TO PSYCH .

The doctor writes in her chart. Diagnosis: schizophrenia.

The woman, unlike David Lurie, does exist. Ive seen her in the eyes of an eight-year-old boy, an eighty-six-year-old woman, and a teenager. She also exists inside of me, in the darkest corners of my psyche, as a mirror image of what so easily could have happened to me at age twenty-four, had I not been spared the final move to the psychiatric ward by the ingenuity and lucky guess of a thoughtful, creative doctor who pinpointed a physical symptominflammation in my brainand rescued me from misdiagnosis. Were it not for that twist of fortune, I would likely be lost inside our broken mental health system or, worse, a casualty of itall on account of a treatable autoimmune disease masquerading as schizophrenia.

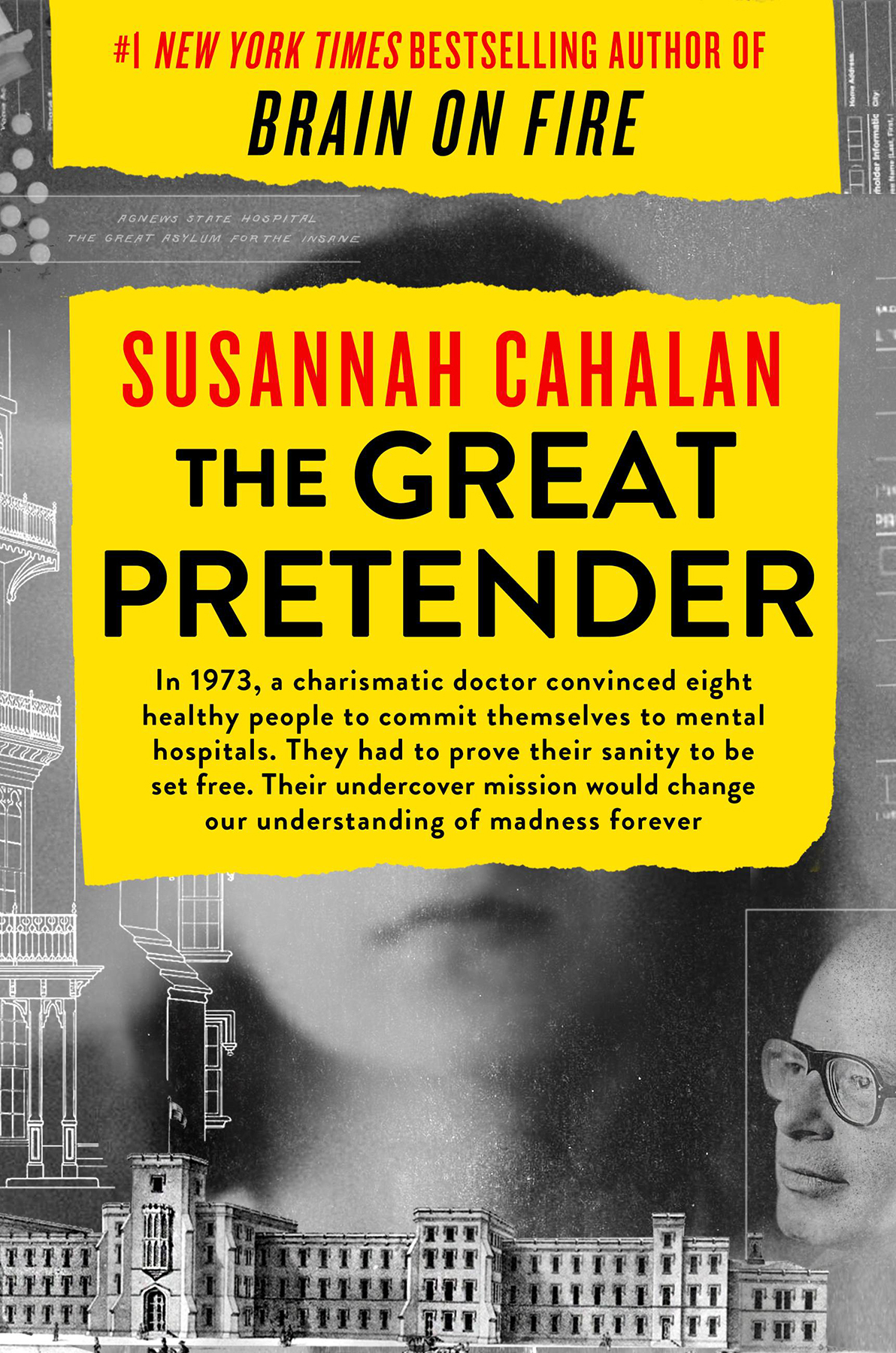

The imaginary David Lurie, I would learn, was the original pseudopatient, the first of eight sane, healthy men and women who, almost fifty years ago, voluntarily committed themselves to psychiatric institutions to test firsthand if doctors and staff could distinguish sanity from insanity. They were part of a famously groundbreaking scientific study that, in 1973, would upend the field of psychiatry and fundamentally change the national conversation around mental health. That study, published as On Being Sane in Insane Places, drastically reshaped psychiatry, and in doing so sparked a debate about not only the proper treatment of the mentally ill but also how we define and deploy the loaded term mental illness.

For very different reasons, and in very different ways, David Lurie and I held parallel roles. We were ambassadors between the world of the sane and the world of the mentally ill, a bridge to help others understand the divide: what was real, and what was not.

Or so I thought.

In the words of medical historian Edward Shorter, The history of psychiatry is a minefield. Reader: Beware of shrapnel.