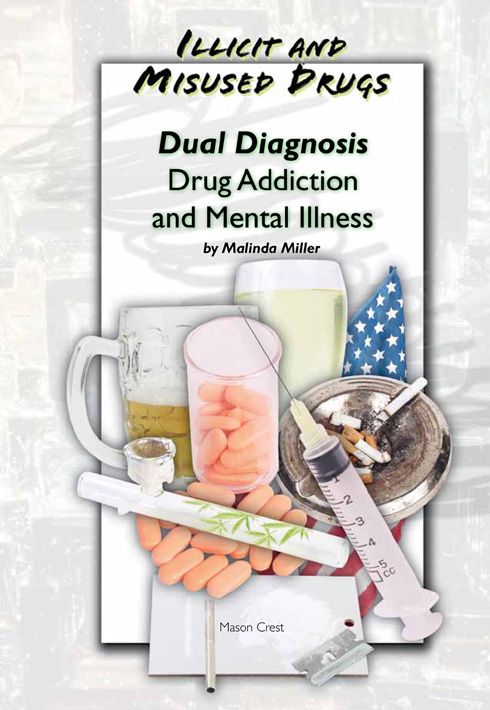

Dual Diagnosis

Drug Addiction and Mental Illness

ILLICIT AND MISUSED DRUGS

Abusing Over-the-Counter Drugs:

Illicit Uses for Everyday Drugs

Addiction in America:

Society, Psychology, and Heredity

Addiction Treatment: Escaping the Trap

Alcohol Addiction: Not Worth the Buzz

Cocaine: The Rush to Destruction

Dual Diagnosis: Drug Addiction and Mental Illness

Ecstasy: Dangerous Euphoria

Hallucinogens: Unreal Visions

Heroin and Other Opioids:

Poppies Perilous Children

Inhalants and Solvents: Sniffing Disaster

Marijuana: Mind-Altering Weed

Methamphetamine: Unsafe Speed

Natural and Everyday Drugs:

A False Sense of Security

Painkillers: Prescription Dependency

Recreational Ritalin: The Not-So-Smart Drug

Sedatives and Hypnotics: Deadly Downers

Steroids: Pumped Up and Dangerous

Tobacco: Through the Smoke Screen

| Mason Crest

370 Reed Road

Broomall, Pennsylvania 19008

www.masoncrest.com |

Copyright 2013 by Mason Crest, an imprint of National Highlights, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the publisher.

Printed in the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan.

First printing

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Miller, Malinda, 1979

Dual diagnosis : drug addiction and mental illness / Malinda Miller.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-4222-2430-4 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-1-4222-2424-3 (hardcover series)

ISBN 978-1-4222-9294-0 (ebook)

1. Drug addictsMental health. 2. Mentally illSubstance use.

3. Dual diagnosisPatientsRehabilitation. I. Title.

RC564.M537 2013

616.86dc23

2012013832

Interior design by Benjamin Stewart.

Cover design by Torque Advertising + Design.

Produced by Harding House Publishing Services, Inc.

www.hardinghousepages.com

This book is meant to educate and should not be used as an alternative to appropriate medical care. Its creators have made every effort to ensure that the information presented is accuratebut it is not intended to substitute for the help and services of trained professionals.

CONTENTS

CONTENTS

Addicting drugs are among the greatest challenges to health, well-being, and the sense of independence and freedom for which we all striveand yet these drugs are present in the everyday lives of most people. Almost every home has alcohol or tobacco waiting to be used, and has medicine cabinets stocked with possibly outdated but still potentially deadly drugs. Almost everyone has a friend or loved one with an addiction-related problem. Almost everyone seems to have a solution neatly summarized by word or phrase: medicalization, legalization, criminalization, war-on-drugs.

For better and for worse, drug information seems to be everywhere, but what information sources can you trust? How do you separate misinformation (whether deliberate or born of ignorance and prejudice) from the facts? Are prescription drugs safer than street drugs? Is occasional drug use really harmful? Is cigarette smoking more addictive than heroin? Is marijuana safer than alcohol? Are the harms caused by drug use limited to the users? Can some people become addicted following just a few exposures? Is treatment or counseling just for those with serious addiction problems?

These are just a few of the many questions addressed in this series. It is an empowering series because it provides the information and perspectives that can help people come to their own opinions and find answers to the challenges posed by drugs in their own lives. The series also provides further resources for information and assistance, recognizing that no single source has all the answers. It should be of interest and relevance to areas of study spanning biology, chemistry, history, health, social studies and more. Its efforts to provide a real-world context for the information that is clearly presented but not overly simplified should be appreciated by students, teachers, and parents.

The series is especially commendable in that it does not pretend to pose easy answers or imply that all decisions can be made on the basis of simple facts: some challenges have no immediate or simple solutions, and some solutions will need to rely as much upon basic values as basic facts. Despite this, the series should help to at least provide a foundation of knowledge. In the end, it may help as much by pointing out where the solutions are not simple, obvious, or known to work. In fact, at many points, the reader is challenged to think for him- or herself by being asked what his or her opinion is.

A core concept of the series is to recognize that we will never have all the facts, and many of the decisions will never be easy. Hopefully, however, armed with information, perspective, and resources, readers will be better prepared for taking on the challenges posed by addictive drugs in everyday life.

Jack E. Henningfield, Ph.D.

Imagine that your brain is a giant communications center, the hub of all your bodys communication needs. In order for your body to function, the brain must communicate with itself and with every other part of your body. According to researchers who have studied this three-pound communications center, billions of messages are sent and received throughout the brain in a single day, using a complex network of nerve cells (which are called neurons).

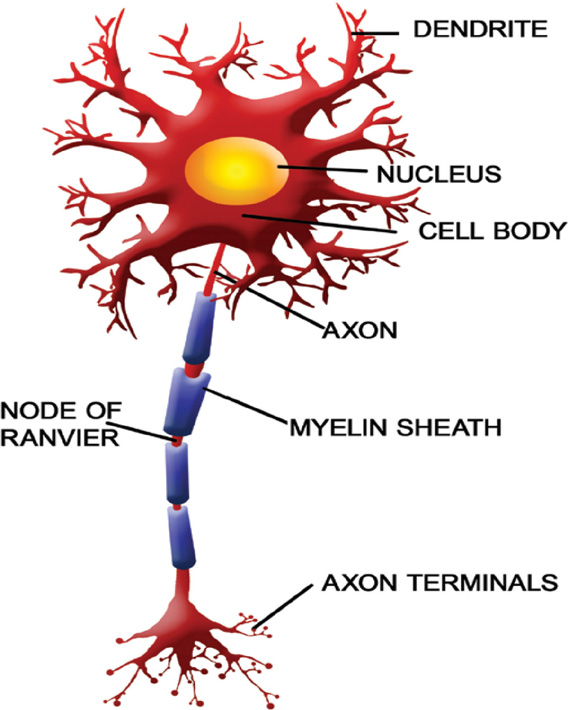

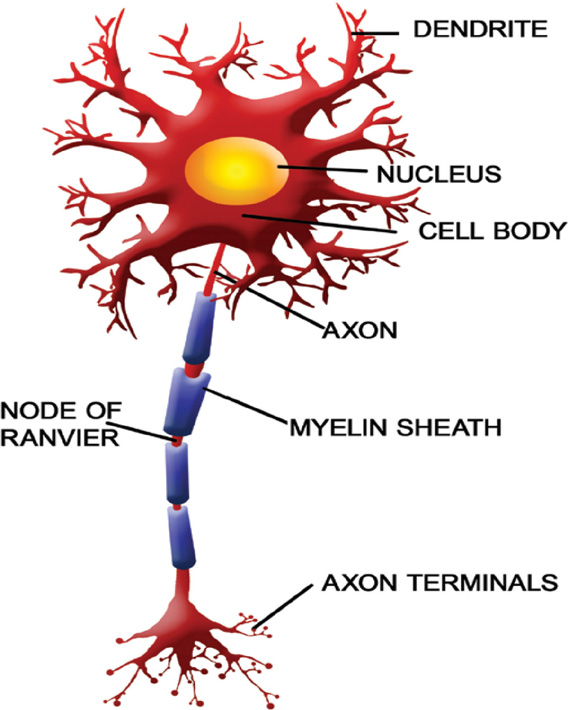

Neurons are made up of three structures: dendrites (several branch-like limbs protruding from the cell body, which receive information), the cell body (the neurons central part, which examines information), and an axon (a single cable-like tail, which sends information). The end of the axon contains several terminal buttons, which overlap the dendrites of other neurons. The neurons, however, dont actually touch each other; they leave a space between called the synapse.

Communication Between Brain Cells

Because neurons dont actually touch each other, they must use special chemicals called neurotransmitters to send and receive messages. This sending and receiving can be a complicated process.

Imagine that youre an outfielder in a baseball game and you want to send a message to the catcher. You attach a note to the ball in your hand, wind up, swing your arm, release the ball, and throw it toward home plate. The baseball, with message attached, flies through air, across mid-field, right to the catchers glove. Though your center fielders glove never touched the catchers glove, you were able to get the message to him. How? You used the ball.

Neurons work together in a similar way in the brain. Using our baseball analogy, you, the center fielder, would be the sending nerve cell, called the presynaptic neuron. The message you want to send is the note attached to the baseball. The catcher would be the receiving cell, called the postsynaptic neuron. To get the message from you, the center fielder (presynaptic neuron), to the catcher (postsynaptic neuron), you have to throw the ball. In the brain, instead of using a baseball to carry the message, the presynaptic neuron (the sending nerve cell) sends its message using chemical neurotransmitters. To throw the ball, the neuron fires, releasing the neurotransmitters (the baseball) into the synapse (the space between the nerve cells or the space between centerfield and home) to carry its message.

Next page

CONTENTS

CONTENTS