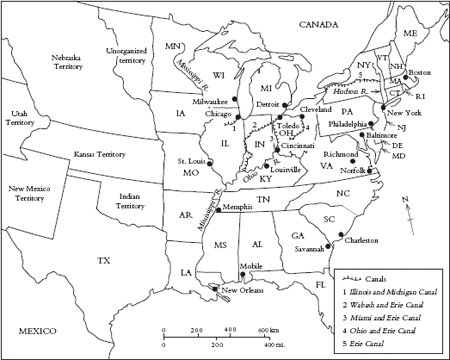

Map 1. Eastern United States, 1860

Introduction

Rethinking the Origins of the Civil War

The Civil War will not go away. The outpouring of books about the causes of the conflict, Abraham Lincoln, and the war itself continues unabated. And for good reason. Whether the issue is race, region, or industrialization, the Civil War has left a deep imprint on modern America. You would think that after all these years historians would agree on why the country came to blows. But they do not. In many ways, to be sure, our knowledge of the era has advanced remarkably, particularly since the 1960s, when I attended graduate school. During the past decades there has been an outpouring of works on politics, the economy, and ideology. Bookshelves fill with biographies and studies of secession, as well as works on the role of African Americans, women, and the less wealthy. Printed volumes of papers and new sources on the Internet have proved a marvelous boon for researchers. So what is the problem? Why cannot historians explain the origins of the Civil Waror at least agree on the general outlines of an interpretation? Part of the difficulty lies with the very abundance of material. No one individual could come close to mastering the relevant secondary and primary sources. Even those who work on a single state can spend decades understanding events in one commonwealth. Part of the problem lies in the nature of what historians do. Despite the dreams of a few theorists, writing history remains as much an art as a science.

Still, there is no reason to abandon the question or succumb to an anything goes relativism. The Civil War is too important to leave alone. It haunts anyone who wonders how the United States came to be the country it is today. Moreover, professional scholars agree on a great deal before they begin to disagree. Almost all acknowledge the widespread racism in the North. Very few see African Americans as docile, childlike creatures. Most historians recognize the dynamic nature of the Northern economy at least from the 1820s onwardeven as they argue about the pace of change in the South. Debates among scholars tend to be exchanges among the well informed. They are clashes between two lawyers who agree about certain facts but differ markedly in the way they interpret those facts.

Clash of Extremes is presented in that spirit. It is written, in part, because of the importance of the topic and the new vistas opened by the literature of the past decades. It is also written because of the problems that beset recent interpretations. If there is a leading explanation today, it is one that harkens back to earlier views. Many historians now affirm the traditional wisdom that slavery caused the Civil War. The North, led by the Republican Party, attacked the institution, the South defended it, and war was the result. James McPherson, the best-known scholar writing today on the Civil War, entitled his great work Battle Cry of Freedom and labeled Lincolns victory the revolution of 1860. He quotes approvingly a Southern newspaper that in 1860 described the triumphant Republicans as a party founded on the single sentimentof hatred of African slavery. Southerners, according to McPherson, had no choice but to respond to this threat

There are, however, difficulties with this idealistic explanation. To begin with, an emphasis on strongly held views about slavery sheds little light on the sequence of events that led to the Civil War. At least since the beginning of the nineteenth century, Northerners had resolutely condemned slavery, even if few advocated immediate abolition. This hostility to bondage, however, marked both the era of compromise, 1820 to 1850, as well as the increasingly bitter clashes of the 1850s, culminating in war. A persuasive interpretation must look elsewhere to explain why a lengthy period of cooperation gave way to one of conflict.

A focus on slavery also explains little about the divisions within the North and the South. It assumes unity in each of these regions when in fact there was fragmentation. Southerners who deemed the Republican victory so threatening that they called for secession comprised a distinct minority within their section. Of the fifteen slave states only seven, located in the Deep South, left the Union before fighting broke out. And many people in those seven states resisted immediate secession. At least 40 percent of voters, and in some cases half, opposed immediate secession in Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana. The Border StatesDelaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouriremained in the Union, while the Upper South statesVirginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Arkansasjoined the Confederacy only after Lincolns call for troops forced them to choose sides. One hundred thousand whites (along with a larger number of blacks) from the Confederate states fought for the Union. There is no question that

Similarly, the North was divided in the years before the war, with only the Republicans rejecting compromise. In 1856 most Northerners backed the Republicans opponents, and even in 1860 45 percent of the North voted for a candidate other than Lincoln. A convincing explanation must shed light on all groups and not simply focus on those whose outlook fits the interpretation.

Finally, the idealistic interpretation distorts the policies and positions of the Republican Party. Unquestionably Republicans, like virtually all free state residents, condemned slavery. But for most Republicans, opposition to bondage was limited to battling its extension into the West. Few Republicans advocated ending slaveryexcept in the distant future. Party members roundly rejected abolitionist demands for immediate action. Moreover, most Republicans (like most Northerners) were racists and had little interest in expanding the rights of free blacks. Indeed, many Republicans advocated free soil and a prohibition on the emigration to the West of all African Americans, free and slave. Blocking the spread of slavery was an important stance and one that frightened many in the South. But this position must not be equated with a humanitarian concern for the plight of African Americans. For most Republicans nonextension was more an economic policy designed to secure Northern domination of Western lands than the initial step in a broad plan to end slavery.

Nor does a celebration of the battle cry of freedom fairly characterize Republican goals once fighting began: the party initially rejected emancipation. Freedom became a war aim only once the North saw its utility in hastening a Confederate defeat. Had the conflict been brought to a quick close, as most Northerners and Southerners confidently assumed it would, slavery would have survived. Even after a year of war, with pressure for emancipation building, Lincoln told the editor Horace Greeley: My paramount object in this struggle is The Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863, conformed to that third option: freeing some of the slaves. It liberated those in the rebel states without threatening the property of Border State slaveholders.

The prevailing interpretation creates an odd dichotomy in explaining the first decades of the Republican Party. Before the war, according to this idealistic approach, the Republicans were humanitarians, driven by their concern for free farmers and African Americans. However, this portrayal of the Republican Party quietly yields to a very different picture in the years after the war. Most accounts depict the postwar Republicans as the corrupt servants of big business. The result is a striking discontinuity. The noble crusaders of the antebellum years become the spoilsmen of the Gilded Age. Of course, parties change. But it is striking how many of the leaders of the 1850s continued to guide the party in the 1870s and later. Idealism existed before the war. But making it the key to understanding the Republicans distorts the record. It fails to explain the actions of a party that, as soon as it took power in 1861, introduced a bold, coherent program to build a national economy and strengthen the dominance of Northern producers.