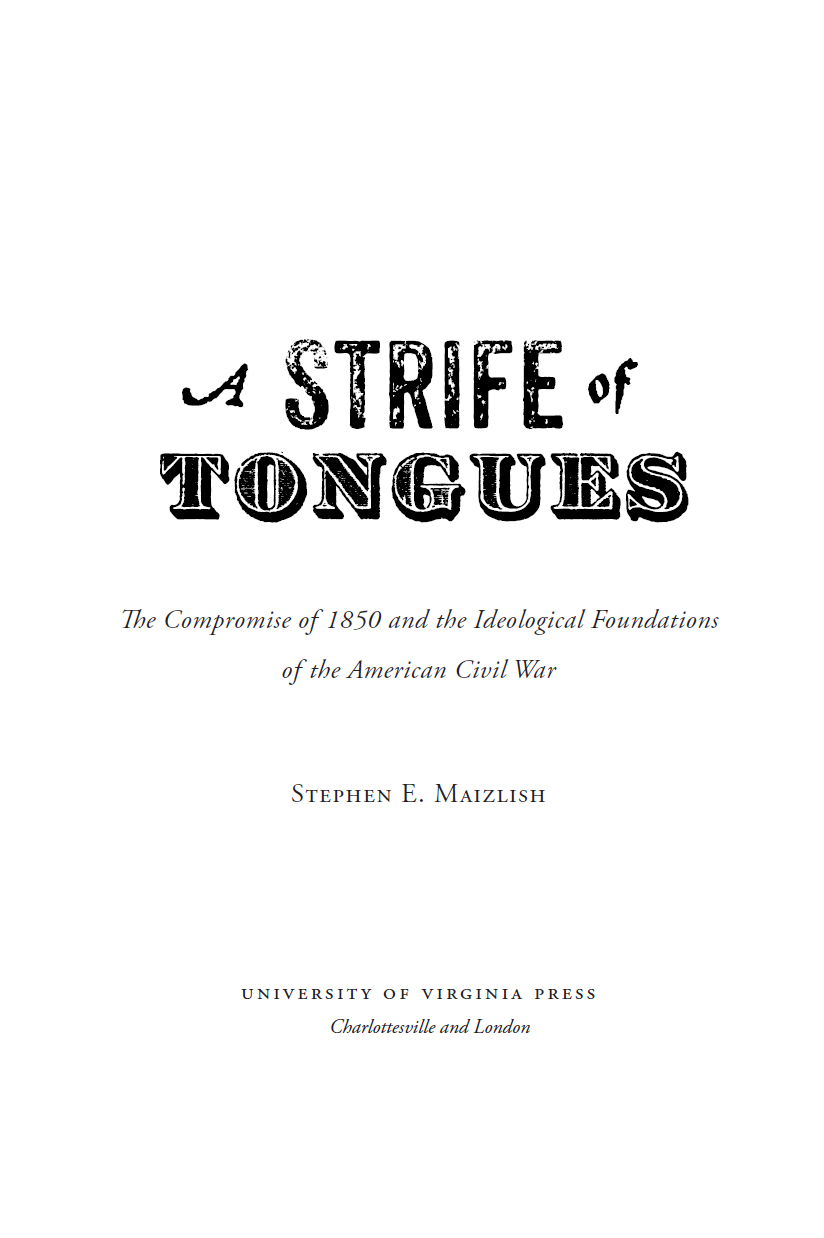

A NATION DIVIDED: STUDIES IN THE CIVIL WAR ERA

ORVILLE VERNON BURTON AND ELIZABETH R. VARON, Editors

University of Virginia Press

2018 by the Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

First published 2018

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

ISBN 978-0-8139-4119-6 (cloth)

ISBN 978-0-8139-4120-2 (ebook)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress.

Cover art: Scene in Uncle Sams Senate by E.W.C. (Edward Williams Clay). This sketch depicts the armed confrontation between Mississippi senator Henry Foote and Missouri senator Thomas Hart Benton on April 17, 1850. (Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-4835)

For Joyce and Rivka

I have thus far abstained from any participation in that strife of tongues which has so long been raging around us.

Robert Winthrop, February 21, 1850

Oh how great is thy goodness, which thou has laid up for them that fear thee; which thou has wrought for them that trust in thee before the sons of men! Thou shalt hide them in the secret of thy presence from the pride of man: Thou shalt keep them secretly in a pavilion from the strife of tongues.

Psalm 31:1920

ILLUSTRATIONS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Kenneth Stampp and William Gienapp taught me both the joys and the rigors of historical inquiry. Each demanded of himself an unyieldingly high standard of scholarship and expected the same from others. Without their inspiring example and the supportive warmth of their friendship, none of my own attempts at scholarship would have been possible. They are deeply missed by those who benefited from their historical insights and from their unreserved dedication to their colleagues, students, and friends.

Several administrators and colleagues at the University of TexasArlington gave this project important support as it developed and grew. History Department chair Marvin Dulaney, who generously read a portion of this manuscript, along with the offices of the dean of liberal arts, the provost, and the university president, deserve special mention.

Richard Holway, Bonnie Gill, Mark Mones, and the entire staff at the University of Virginia Press have proved to be an unfailing pleasure to work with. Their experience, expertise, and commitment to this project improved this book in many ways. I am also grateful to the presss anonymous readers, whose suggestions enhanced the manuscript, and to Margaret Hogan for her skilled copyediting. In addition, I am deeply indebted to the wonderful, dedicated librarians at the over forty archives I visited and at the more than twenty additional libraries that supplied me with photocopied materials during the course of my research for this book.

Many colleagues and friends offered valuable support. Their backing enabled me to pursue this project with confidence. Richard Allen, Sheri Allen, Oliver Bateman, Richard Carwardine, Larry Gerber, Thavolia Glymph, Marcy Paul, Cristina Salinas, Rachel Shelden, and the late Barbara Shilo all gave me important encouragement at critical junctures.

Four colleagues at the University of TexasArlington provided me with crucial assistance in writing and organizing this book. David Narrett freely shared his comprehensive knowledge of the revolutionary era, allowing me to test the memories of the generation of 1850. John Garrigus encouraged my use of digital research tools without which this project could not have been undertaken. Andrew Milson generously contributed his graphic skills, helping to construct the charts in appendix B. And Ryan Hamzeh expertly converted those charts into the required format.

Several friends and colleagues read all or parts of the manuscript. James Brewer Stewart, Kristen Oertel, and Ben Serby offered useful suggestions. Robert Abzug was, as always, wise in his counsel and generous in his support. Daniel Crofts gave me enthusiastic encouragement when I needed it most, and Lisa Rubens, a friend for many decades, was a dependable source of useful advice and perceptive comments.

William Freehling, my first instructor in graduate school, gave the manuscript a critical reading, supplied crucial advice, and encouraged me with his characteristic good cheer. From the very beginning of this project, Christopher Morris listened tirelessly to my reports on the sources I read and the ideas I developed from them. He was always available to make important recommendations and provide cautionary insights. Alison Parker helped me weather countless crises. Her encouragement and unstinting faith in my ability to succeed provided me with the resolve necessary to bring this project to its completion.

The late Michael Morrison offered perceptive observations as I charted and re-charted the course of my work. His strong command of the period proved exceptionally helpful, and his careful, detailed reading of the manuscript identified errors large and small. But most of all, his tenacious support kept me optimistic and determined.

For over forty years of friendship, James Roger Sharp has been a steady, constant source of strength and support. He read an early draft of the manuscript and offered numerous key suggestions that advanced the project in many important ways. His thorough knowledge of antebellum America, his sensitive understanding of the profession, and his experienced guidance were invaluable for this study as they have been throughout my career.

Rivka Maizlish was absolutely unyielding in her confidence in this project and her belief in my ability to complete it. She supported my adoption of a cultural and intellectual history approach and taught me the value of applying its insights to the study of the Compromise. Again and again, she wisely insisted that I remain loyal to the original purpose of this book and, based on her own expertise, offered innumerable insights into the material I was examining. But above all, as our daughter, Rivka has been an endless source of joy and pride, and her love an enduring source of strength. I have dedicated this book to her and to Joyce Goldberg, whose love and devotion have sustained me in this project as they have in all of life. She read every passage of this book many times over, considering every word, every comma, and every argument with the same thought and care that she applies to her own scholarship and to all things. Her wise judgments have kept me focused on what is important in life, and her love has given me the confidence to persevere and prevail.

Introduction

This is a cultural and intellectual history of a political event. It is not a traditional political history, nor is it a history of the Compromise of 1850. Rather, this book examines what the debates surrounding the Compromise reveal about the broad range of foundational beliefs and values held by northerners and southerners in Congress that, taken together, formed an ideological divide between the sections. That ideological divide would dominate the sectional battles of the 1850s and give definition, meaning, and force to the greater conflict that lay ahead.

This study began with a question: what was it like for those in each section of the Union, who had been demonizing one another over the issue of slavery for decades, to be thrown into the same room for nine months, forced to listen to the diatribes of their opponents, and then respond as they debated the future of slavery in the lands acquired in the recent Mexican War, along with other pressing sectional issues facing the country? Additional questions followed: How did the sectional conflict appear when it took this form of engagement? What did the language of combat, the strife of tongues as Massachusetts Whig representative Robert Winthrop called it, reveal about the basic systems of belief, the ideologies that dominated each section on the eve of the Civil War? And how did that language refocus and deepen the countrys sectional divisions as they developed on the national stage?

Next page