Table of Contents

For Ruth

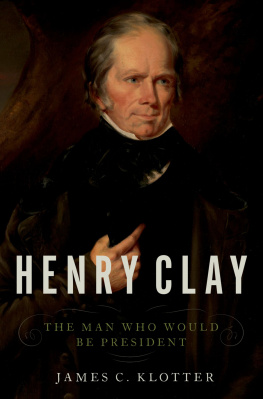

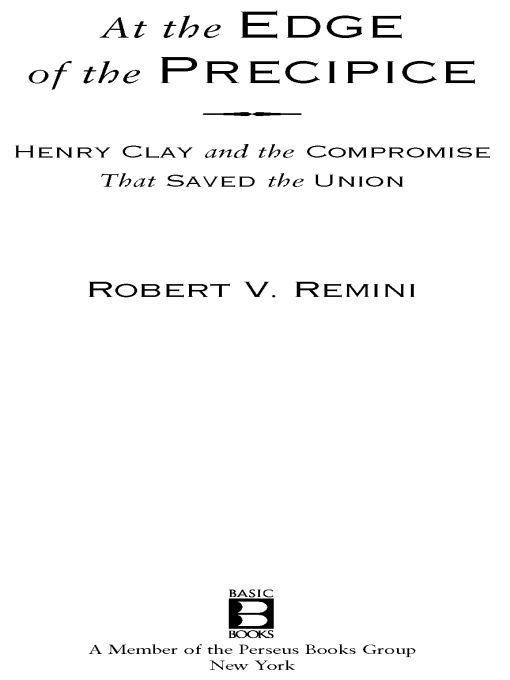

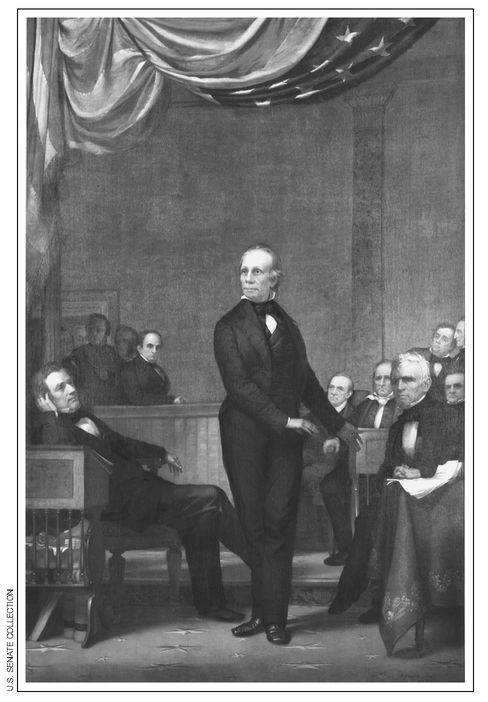

Henry Clay speaking in the

Old Senate Chamber.

This 7 by 11 foot, one-hundred-pound portrait of Henry Clay speaking in the Old Senate Chamber, and surrounded left to right by several of his friends and colleaguesWilliam H. Seward, R. M. T. Hunter, Robert Letcher, General Winfield Scott, George Robertson, Daniel Webster, Joseph Rogers Underwood, Sam Houston, John Crittenden, Lewis Cass, Thomas Hart Benton, and Stephen A. Douglaswas painted by Phineas Staunton in 1867 for a competition sponsored by the state of Kentucky to memorialize the Great Compromiser. The painting eventually wound up in the Le Roy Historical Society in upstate New York and lay, virtually unknown, for fifty years in a storage room. Amy Elizabeth Burton, an art historian in the Curators Office of the U.S. Senate, discovered the painting and arranged for its removal to the Senate. The painting was torn and covered with dirt and grime; it took seventeen months for the painting and its frame to be restored. It now hangs on a wall in a staircase leading to the Senate chamber in the U.S. Capitol. It is an excellent likeness of Clay, which very few people have seen, and shows him pointing to a document bearing the date 1851.

PREFACE

In 1850, a decade prior to the election of Abraham Lincoln, the secession of southern states, and the firing on Fort Sumter in April 1861, the Union of American states came close to being irreparably smashed. Had that happened, it is arguable that two or more independent nations would have been formed, thus permanently dissolving what was once the United States of America. And had war resulted between the free states of the North and the slaves states of the South in 1850, rather than a decade later, it seems likely that the more militant South would have defeated the much weaker North and made good its separation from the Union. Once the great men of the antebellum era passed awaymen such as Andrew Jackson, Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, and John C. Calhounthe nation lacked individuals in positions of power who were passionately devoted to the Union, men possessing genuine leadership ability who could find solutions to the crises that arose repeatedly over the issue of slavery and thereby threatened the liberty of all. Throughout the decade of the 1850s, the best the nation could offer to stand at the head of government were such figures as Millard Fillmore, Franklin Pierce, and James Buchanan, not one of whom could have provided the statesmanship by which the Union could be kept intact.

Fortunately, in 1850, the crisis was averted. It was averted because there were a number of men in Congress who were willing to compromiseand not simply on one issue, like slavery, but on many related issues that divided North and South, such as congressional control of the territories, the admission of California, the New Mexico boundary, and the Texas debt.

In this book I seek to explain the extent of the crisis, its long history, why it was so catastrophic, its importance for the nation, and its results. I also seek to show the importance of compromise in resolving problems of great magnitude in the history of the country. It has proven time and time again that little of lasting importance can be accomplished without a willingness on the part of all involved to seek to accommodate one anothers needs and demands. This point is especially important today when the nation faces myriad problems, both foreign and domestic, that defy easy solution, and that will, in all likelihood, require both major political parties to agree to compromise their differences. With severe economic problems that threaten to pitch the nation into a deep recession; with other domestic issues, such as health care, energy, immigration, and social concerns such as abortion and gay marriage; with wars in the Middle East that verge on escalation throughout the region; and with terrorism rampant around the globe, compromise on the part of this nations political leaders, and the leaders of other countries, becomes all the more necessary.

The Compromise of 1850 is a prime example of how close this nation came to a catastrophic smash-up, and the way the power brokers of that period avoided that disasterjust in time. The Compromise gave the North ten years to build its industrial strength and enable it to overpower the South when war finally broke out. It also gave the North ten years to find a leader who could save the Union. His name: Abraham Lincoln.

COMPROMISE IN THE NATIONS EARLY HISTORY

The Founders of this nationmen of the Enlightenmentunderstood the importance of compromise in achieving important goals. Because they put together a bundle of compromises that resolved their many problems, they succeeded in writing the Constitution of the United States, which created a republic that has survived for more than two hundred years. Their compromises produced a Union of thirteen separate, sovereign, independent states. They compromised on the structure of the legislature and the extent of its duties; on the method by which members of Congress would be elected; and on the powers delegated to each branch of government. They compromised over the demands of large and small states, and they compromised on the existence of slavery and the role it would play in the distribution of representatives in the lower house of Congress. Indeed, the Constitution is one long collection of compromises.

When the Founders finished their work and submitted it to the people of the several states for their ratification, they hoped that their own and succeeding generations would also understand the value and importance of compromise and how essential it was in resolving conflict and ensuring peace. And yet, just thirty years later, the Union almost came apart.

The origins of the crisis of 1850 lay in decisions made nearly half a century earlier. To start, President Thomas Jefferson in 1803 purchased the Louisiana Territory from Francean immense area that doubled the size of the countrythat triggered a titanic battle in Congress in 1819 when Missouri, carved from this territory, applied for admission into the Union as a slave state. Missouri was the first territory to be located completely west of the Mississippi River. Unfortunately, if granted, this request for admission would upset the balance between the number of free and slave states in the Union, tilting the number in favor of the slave states. Northerners reacted angrily. To rectify this problem, Representative James Tallmadge Jr. of New York proposed amending the enabling act that would admit Missouri as a state so that, in time, Missouri would become a free state. His amendment prohibited the further introduction of slaves into the territory and would free those slave children born in Missouri upon reaching the age of twenty-five.

Southerners exploded with indignation. This obvious ploy on the part of northerners to restrict the expansion of slavery was not only dastardly, they cried, but a violation of the Constitution. Northerners were not content with the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 forbidding slavery north of the Ohio River, southerners ranted. Now they argued for the right of Congress to legislate on slavery in the territories and the right to abolish slavery for the entire territory of the Louisiana Purchase. On the floor of Congress, Representative Thomas W. Cobb of Georgia shook his fist at Tallmadge. If you persist, he screamed, the Union will be dissolved. You have kindled a fire which all the waters of the ocean cannot put out, which seas of blood can only extinguish.