Other Books by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler

Prologue

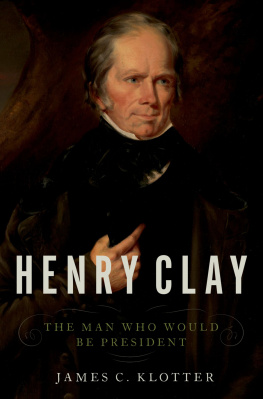

B EFORE THE CLOCKS struck noon, Washingtons church bells began to toll, a signal to the capital that it was over. The telegraph sent the news across the country, and bells began to ring in cities and towns from the Atlantic coast to the deep interior. One of those first telegrams was sent to Lexington, Kentucky: My father is no more. He has passed without pain into eternity. Soon that message was speeding to the house nearby called Ashland, where an old woman at last had the hard news she had been expecting for months. Her husband of more than fifty years was dead. Lucretia Clay was a widow. The bells in Lexington were already ringing.

Henry Clay was dead. Shop owners across the country paused to stare briefly into the distance before pulling shades and locking doors. Men reflexively pulled watches from their vest pockets and noted the time. The immediacy of the news was sobering. Clay had died at seventeen minutes after eleven that very morning of June 29, 1852. Only a few years before, reports of his death would have seeped out of Washington only as fast as the post office and knowledgeable travelers could carry them. People on rivers would have heard about it first, possibly in days, but days would have stretched into weeks before most people learned that the greatest political figure in the nation was dead. Time would have cushioned the blow, weakening its power until it became a piece of history, something that had happened a long way off, a long time ago.

The telegraph made the news of Clays death instant and therefore indelible. Only hours passed before cities from Maine to Missouri began draping themselves in crepe and men from Savannah to St. Louis began pulling on black armbands. Washington, already slowed by summers heat, came to a halt. President Millard Fillmore shut down the government, and Congress immediately adjourned. Members scattered to boardinghouses, hotels, and taverns, some to draft eulogies they would deliver the next day in the legislative chambers that

On June 30, the House of Representatives and the Senate heard recollections of Henry Clay. His passing was not unexpectedhe had lain ill in his rooms at the National Hotel for months, and his visitors had been on what amounted to a deathwatch for weeksbut the expectation did not make its actual occurrence any less piercing. The sense that Clays death was ending a momentous chapter in the countrys history was also sobering. A little more than two years before, Clays celebrated contemporary John C. Calhoun had died, and another, Daniel Webster, was gradually succumbing to maladies that were soon to carry him off as well. These three had become the fabled Great Triumvirate of American government. More than mere symbols of the Republic, they became personifications of it. The South Carolinian Calhoun was the South with its growing frustrations and emerging belligerency over the slavery issue. New Englands Webster had become the conflicting ambiguities of the North with its moral repugnance over slavery and its allegiance to a country constitutionally bound to slaverys preservation. And the Kentuckian Clay was that national ambiguity defined. He was a westerner from the South. Yet he was not southern, because he deplored slavery. His owning slaves, however, meant that he was not northern. When an admirer said that you find nothing that is not essentially AMERICAN in his life, it was meant as a compliment in a divisively sectional time, but in retrospect it was also a warning to the country. Like Henry Clay, it could not long continue to own slaves while denouncing slavery.

When Congress met on June 30, however, it was more in the mood to celebrate Clays life than to find portents in his death. Some members quoted poetry; some of it was good. Several remarked on his humble birth and his admirable efforts to rise above it, a theme that had already become an American political staple by the mid-nineteenth century, an obligatory credential for establishing ones relationship with the people. And though in some cases, such as Clays, it was an exaggeration for election campaigns, he had indeed risen, and no less spectacularly because he started from relative comfort rather than poverty. His success resulted from ceaseless labor and fastidious attention to detail. Kentuckian Joseph Underwood reminded the Senate that Clay had been neat in everything from his handkerchiefs to his handwriting. Underwood was not just talking about wardrobes and penmanship.

All realized, some grudgingly, that Clay had become a great statesman. They also had to admitagain, some grudginglythat he had been usually a jovial adversary with his opponents and always an endearing companion to his friends. New York Whig William Seward, destined to become Abraham Lincolns

The reference to Caesar was ironic. The closest thing to an American Caesar in Clays time had been his most implacable foe, Andrew Jackson. For near a quarter of a century, Virginias Charles Faulkner observed, this great Republic has been convulsed to its centre by the great divisions which have sprung from their respective opinions, policy, and personal destinies. But that didnt say the half of it. Andrew Jacksons shadow had cast a pall over Clays political life for more than a quarter century in some way or other, starting with Clays criticism of Jacksons foray into Florida in 1818, their rivalry in the 1824 presidential contest, and clashes during Jacksons presidency that included the titanic struggle over the national bank, a political brawl so devastating that it was called a war. Clay had lost that war. In fact, he had lost almost every time he challenged Andrew Jackson, and worse, he was defined for many Americans by the accusation Jackson and his friends leveled at Clay in 1825. He had, they said, entered into a corrupt bargain with John Quincy Adams to give Adams the presidency in exchange for Clays appointment as secretary of state, a presumed springboard to the presidency. This example of what Americans now call the politics of personal destruction was called by Clays generation simple candor by his foes, base slander by his friends. The argument over who was right would outlive both Jackson, who died in 1845, and Clay, but as his colleagues took the measure of his life on that hot June day, the question momentarily became irrelevant. When John Breckinridge, a young Democrat from Clays Kentucky, proclaimed that Clay had been in the public service for fifty years, and never attempted to deceive his countrymen, it was a slightly oblique jab at Jackson and the charge he had perpetuated. Walker Brooke reminded the Senate and James Brooks the House of Clays famous response when advised to modify his principles for political advantage: Sir, I had rather be right than be President. Clays repeated failures as a presidential aspirant are evidence that he apparently meant it.