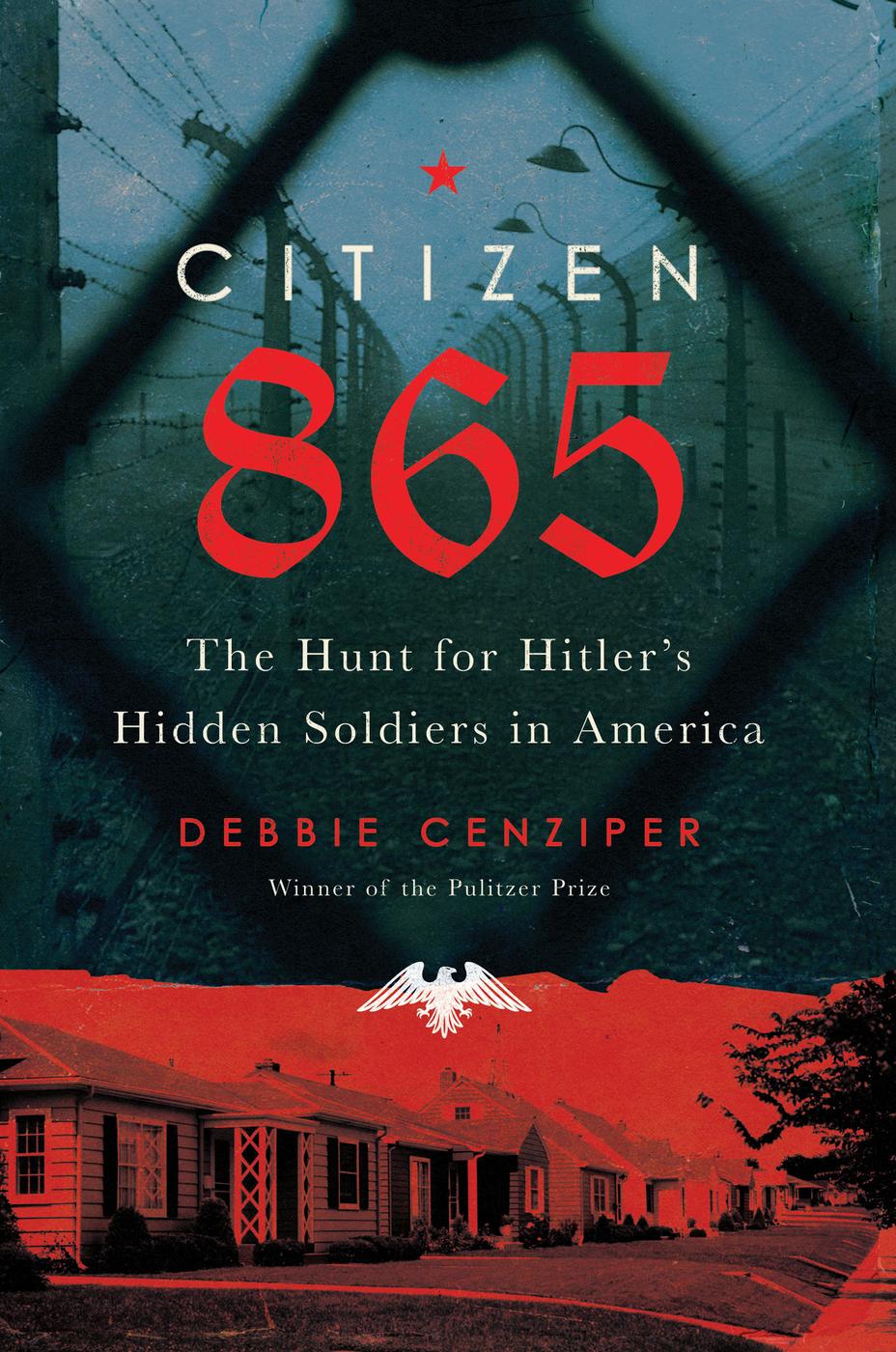

Copyright 2019 by Debbie Cenziper

Cover design by Jeff Miller/Faceout Studio

Cover images: Houses Photo by H. Armstrong Roberts/ClassicStock/

Getty Images; Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp Jonathan Noden

Wilkinson/Shutterstock; Eagle pne/Shutterstock; texture Shutterstock

Cover copyright 2019 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

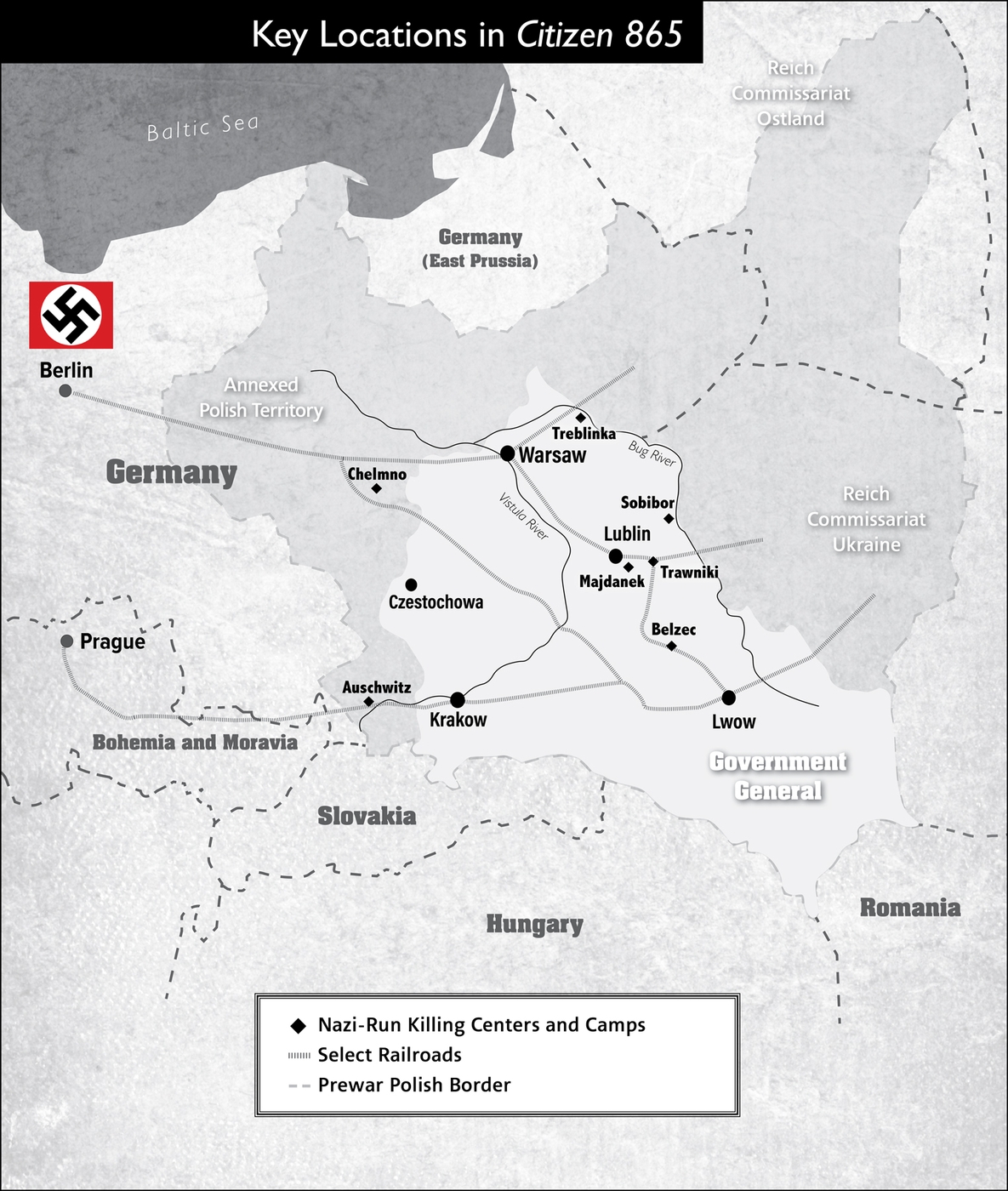

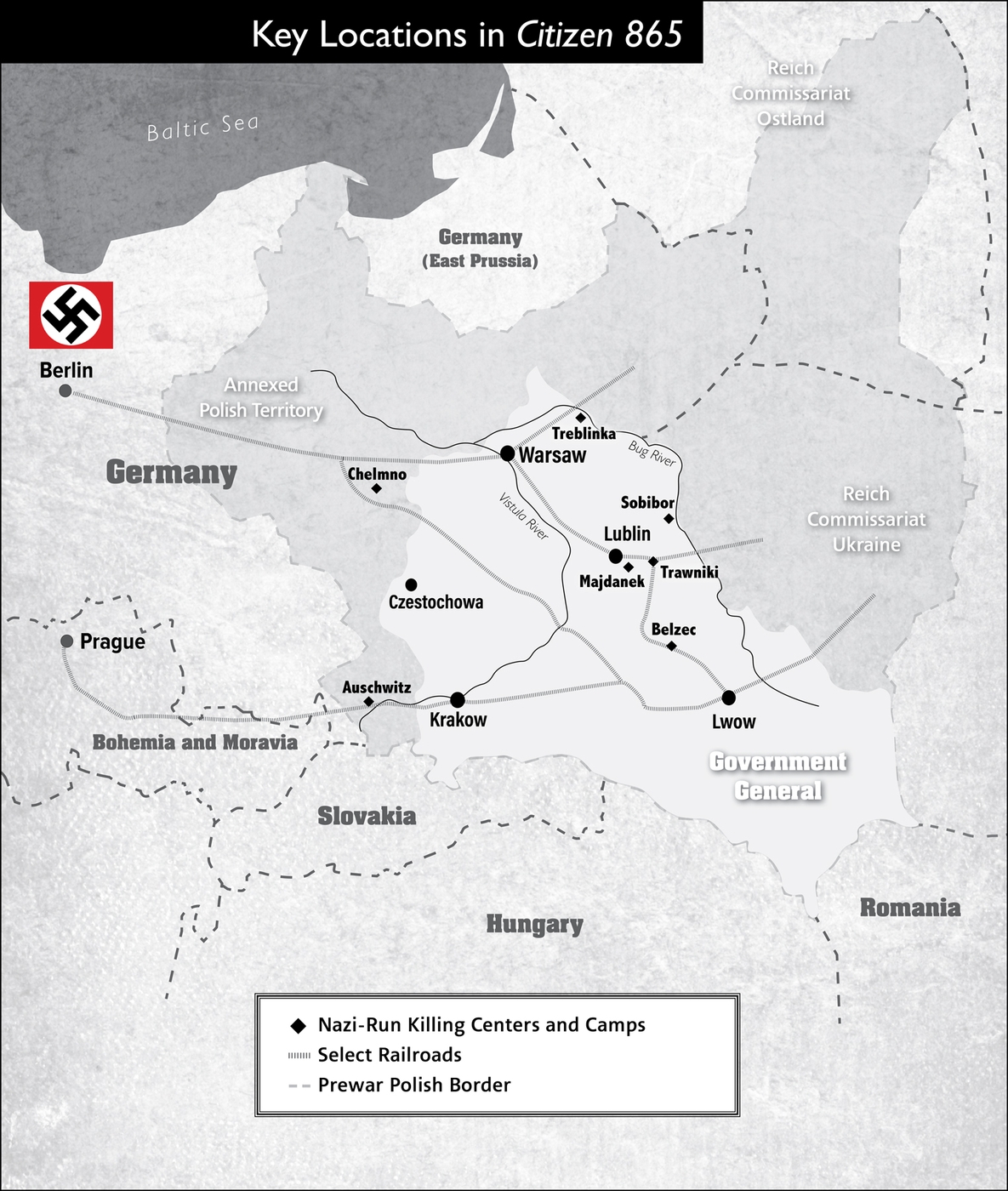

Map of Eastern Europe courtesy of Worth Chollar

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Hachette Books

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10104

HachetteBooks.com

Twitter.com/HachetteBooks

Instagram.com/HachetteBooks

Printed in the United States of America

First Edition: November 2019

Hachette Books is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Hachette Books name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

Print book interior design by Tom Louie.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for.

ISBNs: 978-0-316-44965-6 (hardcover), 978-0-316-44966-3 (ebook)

E3-20191022-DA-NF-ORI

E3-20190925-DA-NF-ORI

For Brett and Zack

with love

Explore book giveaways, sneak peeks, deals, and more.

Tap here to learn more.

At a crowded holiday party in 2016, I met a lawyer from the US Department of Justice. Over a long conversation, Robin Gold described the history and mission of a unit deep inside the massive federal agency that had raced against time to track, identify, and bring to justice Nazi perpetrators found in Americas cities and suburbs in the years after World War II. For three decades, the Office of Special Investigations (OSI) pursued a series of high-profile cases against concentration camp guards, police leaders, Nazi collaborators, and propagandists. I found one lesser-known investigation particularly compelling: the search for the men of Trawniki.

Citizen 865 is a story about darkness but also about light, the pursuit of truth by a team of American Nazi hunters that worked to expose the men behind the most lethal operation in the Holocaust. Year after year, the team scrambled to hold these collaborators accountable for their crimes, not only for those who had perished in the war but also for those who had survived, and for the benefit of a world that too often finds itself in the exact same place more than seventy years later, forced to explain bigotry, hate, and mass murder.

This book is a work of nonfiction based on hundreds of hours of interviews with historians and federal prosecutors and thousands of pages of government documents, Nazi rosters and records, scholarly research, trial transcripts, and court filings. Most of the documents came from the US Department of Justice and the archives of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., which provided access to several dozen boxes of papers, articles, and records donated in 2015 by former OSI historian Peter Black.

Additional research was conducted in the archives and museums of Prague, Warsaw, and Lublin, Poland. Court transcripts, records, and interviews with those who had direct knowledge of conversations allowed me to reconstruct the dialogue in this book.

At the request of family members, the Polish names of survivors Feliks Wojcik and Lucyna Stryjewska have been used. Taped interviews spanning a decade and on-the-ground research in Lublin, Warsaw, and Vienna allowed me to chronicle their wartime journeys.

I also traveled to Trawniki, Poland, where Nazi leaders in the early years of the war recruited a loyal army of foot soldiers. Some of these men would eventually make their way to the United States and live undetected for years, ordinary Americans with extraordinary secrets.

Their lies unraveled under the unflinching glare of history and through the work of men and women who refused to look away.

It speaks well of American justice that it will not close the books on bestiality until the last participant has felt a frisson of fear and is routed from the land of the free.

George F. Will, the Washington Post, 1998

New York City

1992

Nazi recruit 865 ducked into the US Attorneys Office in the Southern District of New York, rode the elevator to the seventh floor, and sat down in a hushed conference room, where three federal prosecutors were waiting. He smiled, a practiced smile, the smile of an old friend. Tufts of silver hair were combed neatly over his ears, and a mustache grown long ago straddled a thin upper lip. He was lean from years of careful eating and late nights spent in the dance halls of Munich after the war, gliding across the floor to music that reminded him of home.

Ready? one of the lawyers asked.

He nodded, clear-eyed and steady, and raised his right hand. I affirm to tell the truth.

His eastern European accent had softened over the years, and the words sounded lyrical, a light and mellow promise. He was an obliging helper who had come when he was called, traveling all this way from a modest frame house on the shoreline of Lake Carmel, sixty miles upstate, where retirement waited on a spit of a beach and in the faded blue dinghies that bobbed along the water.

Even his name was benign, shortened to three quick beats decades earlier when he had stood before an American flag and vowed to defend the Constitution. Jakob Reimer, the newest citizen of the United States, had given himself a new name. Jack.

We could do this in another language, such as German, if you prefer, the lawyer offered.

No, no, Reimer replied. Before these new friends, he would share a great secret. To tell the truth, I used to read and write German.Now I have forgotten.

From across the table, Eli Rosenbaum managed a slight smile. Years earlier, he had questioned a Polish man who once kept meticulous count of how many bullets he had used to kill Jews during a roundup in the war. At the start of the interview, Rosenbaum shook the mans hand and mused to himself that he had earned his annual government salary in that single moment, forced to make pleasantries with a murderer.

Rosenbaum had investigated and prosecuted dozens of Nazi perpetrators since then, concentration camp guards and police leaders who had slipped into the United States with bogus stories about war years spent on farms and in factories, far removed from the killing squads and annihilation centers of occupied Europe. But the case against Reimer was different.

Soon, the US Department of Justice would move to expose one of the most trusted and effective Nazi collaborators discovered on American soil, an elite member of a little-known SS killing force so skillfully deployed in occupied Poland that 1.7 million Jews had been murdered in less than twenty months, the span of two Polish summers.