Contents

Guide

Page List

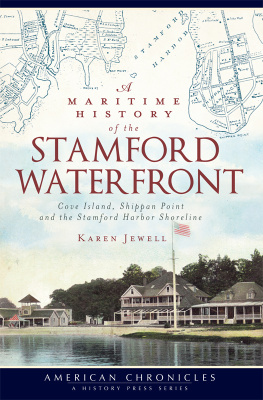

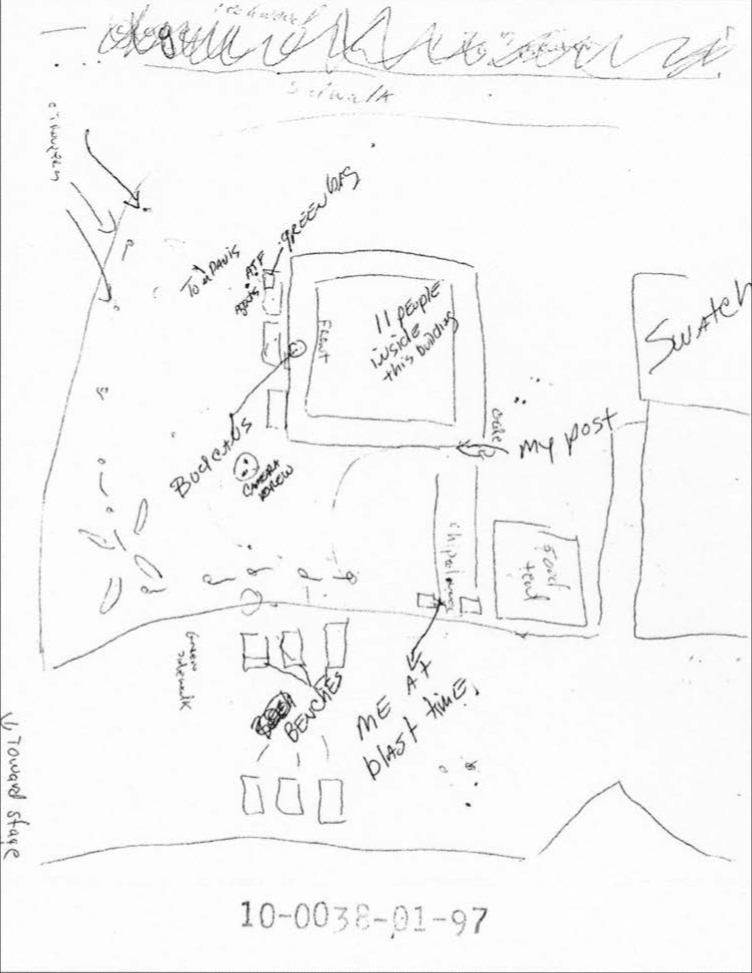

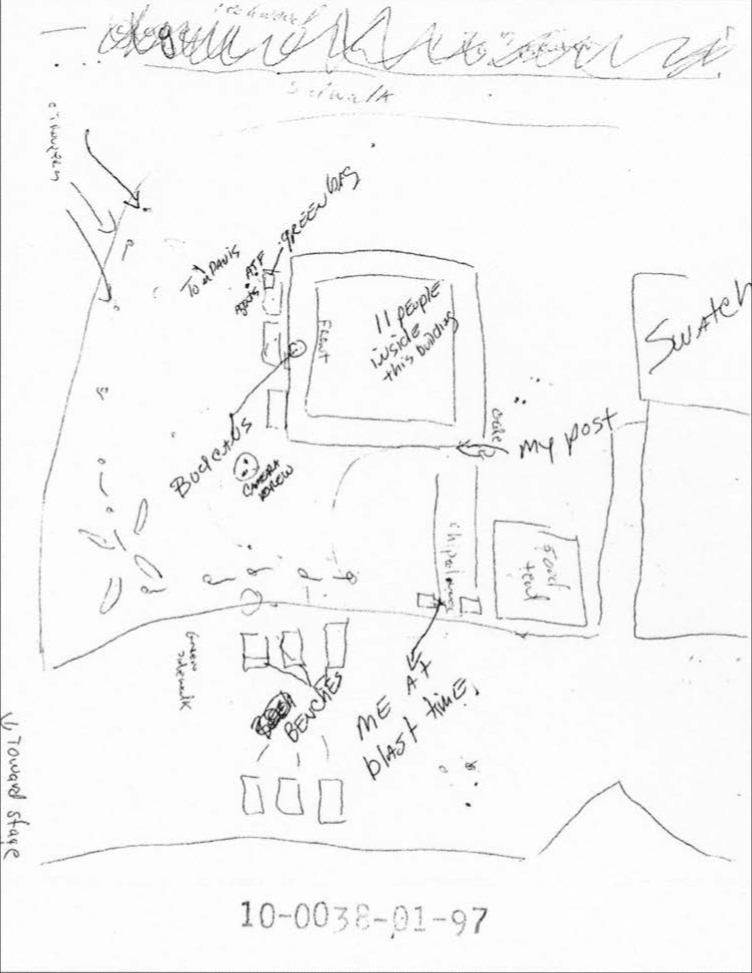

The hand-drawn map that Richard Jewell gave to the FBI the day after the explosion at Centennial Olympic Park

For Diane and Joan,

and for unsung heroes everywhere

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

JULY 26, 1996, DAY 8 OF THE GAMES

Late Friday afternoon, Richard Jewell tousled his Doberman Lacys short brown fur, clicked the TV remote, and hoisted himself off the couch. His standard twelve-hour graveyard shift lay ahead18000600, as hed scribbled in police-speak on his calendar. Jewell swung into the tidy peach-and-white wallpapered kitchen of his moms apartment he temporarily called home. He grabbed a pair of apples from the table and dropped the fruit into his backpack for a future snack. Then he tucked in his white polo shirt, branded on the left chest with a red Olympic flame, snapped on his fanny pack, and slipped out the door of Apartment F-3.

There could hardly have been a more mundane start to the demarcation line of a mans life.

As Jewell was bouncing along in the MARTA subway car, his thoughts turned to how little time he had left in his current work. Since losing two straight law enforcement jobs, his hunt for permanent employment had been frustrating. No police forces were hiring until after the Olympics, and in nine days the Games would be over and hed be unemployed again. He had work to do.

Hopping off the train, Jewell descended International Boulevard, the lime-green lanyard that held his credentials swinging across his ample belly. Downtown Atlanta, traditionally a ghost town after work hours, had become home to the newly constructed Centennial Olympic Park. The twenty-one-acre city of pavilions, stages, and exhibits was now the heartbeat of the worlds largest sporting event, the 1996 Olympic Games. Here in the crowded park, the blue and gold of Sweden mixed with the red and white of Canada, the black, yellow, and red of Germany. Thais mingled joyfully with Tanzanians, Americans, and Brazilians. Entering the park, Jewell could smell the chlorinated water cascading from the fountains shaped to form the Olympic rings. He loved hearing the squeals of the children as the water shot skyward. The park was a party for all ages.

Impatient to start his shift, Jewell marched across the parks pathways constructed of more than two hundred fifty thousand commemorative bricks. Atlantans had purchased the etched pavers for $35 apiece as their way of supporting the host cityand crafting personal messages. By now, Jewell had read hundreds of the two-liners: A smile worth 1000 wordsCES, Loving memory, Lt. Bob Connors, In love and laughter, Terri Geoff, even Elvis Presley 19351977.

Jewell arrived nearly half an hour early at his post, the five-story light and sound tower for the parks main concert stage below. White canvas draped over the steel frame; a sloped roof allowed the summer rains to easily slip off onto the month-old sod below. Jewell approached the day-shift guard, Mark Tillman, and offered to take over before six oclock. When Tillman accepted, Jewell reminded him, Hey, Im cutting you out. Make sure youre here early. By six A.M ., Jewell knew, hed be ready to leave.

Although he was primarily assigned to guard the entrance, Jewell viewed his role as protector of the entire perimeter and interior. So, as Tillman walked away, Jewell carefully circled the tower built for AT&T and NBC, even looking under the three dark-green benches facing the main stage for anything amiss. All clear. Then Jewell climbed the interior stairs of the temporary structure, surveying the five floors to make sure each person had the appropriate blue wristband. He greeted the staffers by name. The process took less than fifteen minutes. It was business as usual, and for Jewell that was just fine.

Good security, Jewell believed, required two elements. The first was attentiveness. One of his favorite games was to close his eyes and try to precisely recall the nearby scenethe color and make of parked cars, signs on the pavilions, the straw panama hat of the Olympic volunteer standing a dozen feet away. The second attribute was unpredictability. Each night, Jewell patrolled at odd intervals. Ten P.M . outside the tower; 10:30 inside. Maybe both again at 11:15, then again at 11:45. Stay sporadic. Dont set patterns.

For the next several hours, Jewell made his checks, taking in the music and the sights. Occasionally, his thoughts drifted to the security risks at hand. In the past three years the world had witnessed a deadly procession of attacks: the World Trade Center truck bomb, two sarin gas attacks in Japan, and the hideous murder of 168 adults and children at an Oklahoma City federal building. Just two days before the Opening Ceremony in Atlanta, TWA Flight 800 had exploded mysteriously off the coast of Long Island, killing all 230 on board. Law enforcement officers in the park were telling Jewell they thought the downing was an act of terror.

Jewell harbored quiet doubts whether his provincial law enforcement experiences in rural Habersham County had prepared him for what might befall the 1996 Games. Me and you are just pretty much good old boys from North Georgia, he confided to a police friend. Hell, what the fuck is terrorism up there to us? Somebody writing on the street signs. Or knocking down mailboxes with a baseball bat, or threatening to kill the neighbors cat.

At 11 P.M ., the R&B band Jack Mack and the Heart Attack took the stage to start their set. Fifty thousand people now jammed the park, with a quarter of them crowded in the expanse between the tower and the main stage. In the middle walked Alice Hawthorne, wearing festive red lipstick, a white Albany State T-shirt, and matching white Keds. She strolled side by side with her daughter Fallon. The night was the perfect birthday gift for the fourteen-year-old, well worth the three-hour drive from South Georgia.

At 12:30 A.M ., as Jewell stood guard, he noticed seven young men who had walked over from the nearby Speedo tent. The group, who the FBI would later call the Speedo Boys, clustered near two of the front green benches. Jewell watched them pull twelve-ounce Budweisers from a green pack. They grabbed the cans, poked holes, and then pulled the tabs to shot-gun the beers in unison. Frat boys, Jewell thought in disdain. Hed seen plenty of that nonsense in his campus cop job at Piedmont College.

Jewell took note of a second green pack under the far left bench occupied by two of the Speedos, but never saw them touch it. Probably just more beer, he decided. These guys could be at it all night. Annoyed, Jewell returned to his post by the entrance on the other side of the tower.

Twenty minutes later, Jewell circled back. The rowdy young men had now littered the ground with over a dozen of their empties. Enough, Jewell fumed. He flagged down Georgia Bureau of Investigation (GBI) Agent Tom Davis, the assistant commander of park security.

Davis embodied Jewells professional dream. Five-foot-eleven and a former college athlete, the agent had a still-muscular physique covered with law enforcement trappingsa state-issued black mesh police vest, badge, phone, walkie-talkie, and 9mm Smith & Wesson. Davis listened carefully as Jewell shouted over the music; the agent agreed to handle the Speedo Boy problem. But moments after Davis left, several of the beer guzzlers breezed past Jewell and began disappearing into the crowd.