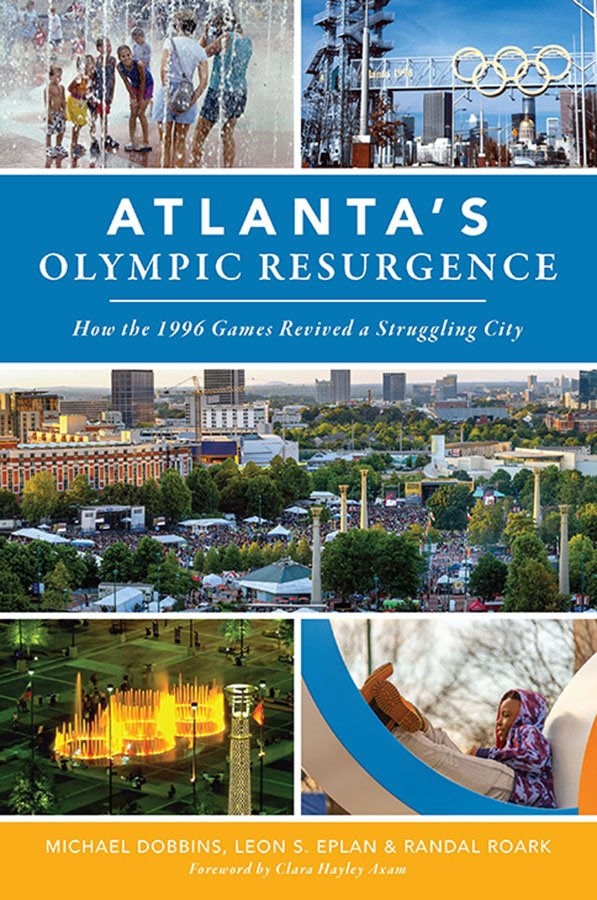

As former mayor of the city of Atlanta and later co-chair of the privately organized committee charged with staging the 1996 Games (ACOG), I had the benefit of both a public and private sector perspective on what it would take to prepare Atlanta to host the 1996 Games. I realized that, though overwhelming, the task of getting the city ready also offered the opportunity to advance Atlantas trajectory as a world class city.

Mayor Maynard Jacksons premise was that we needed a two-pronged approach to realize the full potential of the Games for Atlanta. I agreed. One prong would invest in public facilities to ready them as Games venues. The other prong would invest in Atlantas social and physical infrastructure. To successfully accomplish both, the city would need an unprecedented level of public private cooperation and partnership and at least 150,000 volunteer boots on the ground.

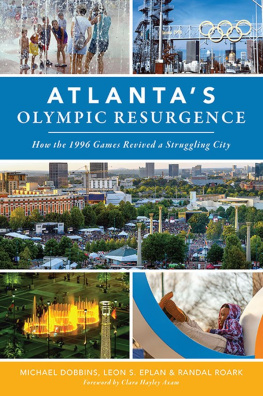

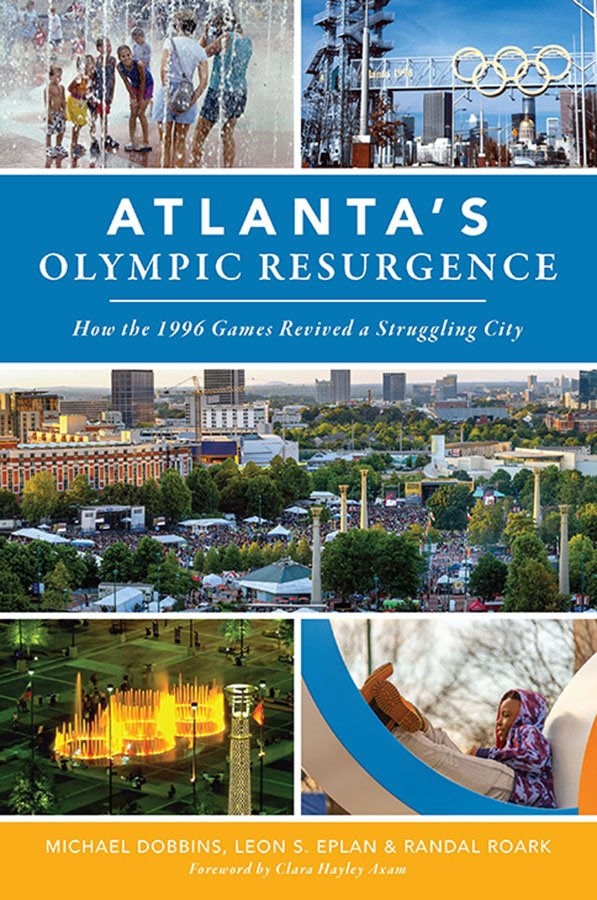

This book provides a compelling account of the dynamics of both the pre- and post-Olympic periods that led to Atlantas emergence on the world stage in 1996 and its continued rise as a world-class city.

the Honorable Andrew J. Young Jr., former U.S. ambassador to the United Nations and former mayor of Atlanta

As Atlantas commissioner of public works during the Olympic period, I was responsible for implementing many of the infrastructure projects in Leon Eplans Olympic Development Program. The coming Olympics sharpened my awareness of the importance of the citys infrastructure needs: sidewalks, sewers, bridges, traffic signals, lighting and more. All of it was critical for the staging of the Games. I became keenly aware that success would require coordination and collaboration across city government, the region, the state, and the private sector.

As the executive director of the Atlanta Regional Commission, I have come to appreciate the multifaceted, multidisciplinary approach needed to revitalize a strong city core, which is indispensable for maintaining a thriving, sustainable region. Coordinated planning, on a small scale and a large scale, in the public sector and the private sector runs to the heart of a successful core and region.

Doug Hooker, Executive Director, Atlanta Regional Commission

The daunting challenge of organizing an event of the size and scope of the Olympic Games within a short time frame, with a definite deadline and with primarily private funding, basically forced the City of Atlanta to bring together the efforts of the public, private and nonprofit sectors as never before.

This collaboration enabled the city not only to successfully organize the worlds greatest sporting event but also to provide a sustainable legacy of physical improvements, economic growth, urban revival and international identity. This long awaited and much needed book provides a comprehensive review and analysis of the positive and lasting impact the Games had on the City and region while also serving as a reminder of what can be accomplished when the public and private sectors work together toward a common goal.

Charlie Battle, original member of the Atlanta bid committee, officer of the Atlanta Committee for the Olympic Games and former president of Central Atlanta Progress

Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2021 by Leon S. Eplan, Randal Roark and Michael Dobbins

All rights reserved

First published 2021

E-Book edition 2021

ISBN 978.1.43967.256.3

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021931153

Print Edition ISBN 978.1.46714.724.8

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the authors or The History Press. The authors and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

I was skeptical from the beginningnot at all sure if Atlanta was serious about embracing Mayor Maynard Jacksons approach to preparing the city for the 1996 Games: twin peaks, one that focused on preparing venues and delivering facilities to house the Games and another that focused on leaving a legacy that would help reboot a city experiencing population decline, disinvestment and increasing inequities. For weeks, the inner-city neighborhoods had been in an uproar over the disruption they anticipated from construction of facilities followed by the throngs of visitors who would invade their neighborhoods to enter those facilities and attend the Games.

My first few months as president of the Corporation for Olympic Development in Atlanta (CODA)created by Mayor Jackson to manage the legacy agendadid little to quell my skepticism. Encouraged by Mayor Jackson and Mayor Andrew Young, I set in motion my plan to speak to public, private, nonprofit and community leadership about their willingness to embrace a twin peaks agenda. And for months, I felt more like a ping pong ball tossed between the sectors than the president of an organization that hoped to leave a legacy for the city we all claimed to love.

In all honesty, Im not sure when it started to occur to the leadership of our city that it would take the collective leadership of the public, private and nonprofit sectors to succeed with either peak. The Atlanta Games were to be privately funded. Atlanta would have to make use of every resource and assetmany of which were public. Policy decisions were required to support the preparations on city streets and private property. Foundation dollars were needed to sweeten the pot, fill in the gaps and cover the shortfalls if the city was to deliver the Games debt-free as promised. And then there were the community voices that insisted that their interest in a better quality of life would not be crushed in the name of economic progress, again.

Perhaps the reality that neither public nor private sector could be successful alone occurred as the city began to face the monumental task of delivering on the promises in the citys successful bid for the Games. Or perhaps it occurred in some of the many robust discussions where the city wrestled with its history of segregation, its identity and what it meant to leave an Olympic legacy. Hindsight has a way of romanticizing historyand sometimes revising it. I bear witness that the revelation of the new reality did not come easy or without tensions. But at some point, the leadership of Atlanta realized that a successful 1996 Games would require a public/private sector partnership like none before and possibly none since.

You, perhaps, will find the answer in the pages of this book. I am sure it is here in the story as told by Leon Eplan, who, as Commissioner of Planning for the City of Atlanta, became the main author of the citys 1996 Games plan; Randal Roark, then professor of architecture and planning at the prestigious Georgia Institute of Technology who became the full-time visionary director of planning for CODA; and Michael Dobbins, the citys post-Games commissioner of planning who had the opportunity to build on the impact of the Olympic Games wake and encourage subsequent development.

Next page