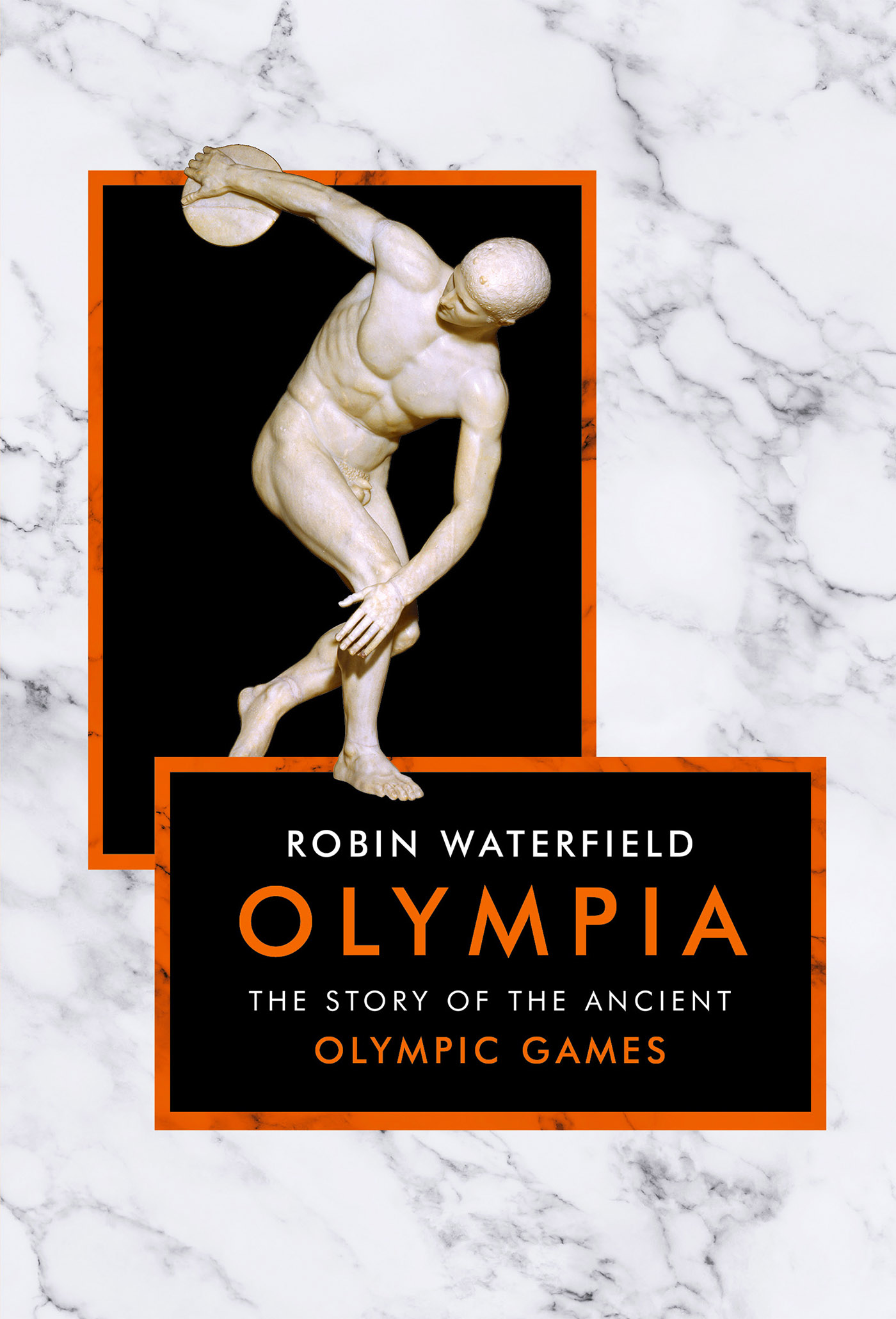

OLYMPIA

Robin Waterfield

AN APOLLO BOOK

www.headofzeus.com

In the northwestern corner of the great eninsula of the Peloponnese, close to the meeting point of the Cladeus and Alpheus rivers, lies a peaceful river valley overlooked by the steep-sided Hill of Cronus. Here, between the eighth century BCE and the fourth century CE, rival athletes competed for glory in the ancient Olympic Games. Every four years, and from every corner of the Mediterranean world from Samos to Syracuse and from Sparta to Smyrna they descended on this quiet corner of southern Greece sacred to Zeus, seeking to excel in disciplines as diverse as sprinting, boxing, wrestling, trumpet-blowing and chariot and mulecart racing.

The victors of these ancient games may have been awarded crowns of olive leaves in recognition of their achievements, but these original Olympics were no idealistic celebration of the classical aesthetic of grace and beauty shared by all of the participating Greek city-states, but often a bitterly contested struggle between political rivals.

Robin Waterfield paints a vivid picture of the reality of the ancient Olympic Games; describes the events in which competitors took part; explores their purpose, rituals and politics; and charts the vicissitudes of their remarkable thousand-year history.

Contents

In memory of my time with

the Stragglers Running Club

and the Hayle Runners

Hercules Milas/Alamy Stock Photo

As with many aspects of the ancient world, it is important to shed preconceptions before approaching the ancient Olympic games. Two stand out. First, the games were part of a religious festival, which is alien to our conception of an athletic meeting. Greek religion was largely a matter of practice rather than faith or belief, and athletic contests were viewed by everyone, contestants and spectators and judges, as participation in a religious rite. Perhaps the athletes felt that, in expending energy, they were offering it to the gods to Zeus in particular, the presiding god of the Olympics. It is likely that they also considered the games entertainment for the gods; they were putting on a show in their honour.

Even the name Olympia had religious connotations, since it was derived from Mount Olympus, the highest mountain in Greece and the legendary home of Zeus and his extended family. Though he may not have been the original deity of the site, it was Zeus Olympius Zeus of Olympus to whom the games were dedicated. One of the first things the athletes did on arrival at Olympia was swear to Zeus that they would abide by the rules of the games. Fines for cheating and other infractions were paid to the god. Sacrifices to various gods and deities punctuated the festival and marked its climax. The Altis, the sacred precinct that constituted the heart of Olympia, was crammed with temples, altars and shrines to deities.

Second, since we are talking about sport, the word might trigger some inappropriate associations in the modern mind, in particular the notion of fair play and the idea that winning is less important than taking part. That sentiment is of course not unknown in our day: Winning isnt everything, said Vince Lombardi, the famous Green Bay Packers coach of the 1960s. Its the only thing. In Greek terms, even though they sometimes noted second and third places as worthy attempts, it was only winning that showed you had earned the favour of the god.

George Orwell famously described sport (or international football matches, at any rate) as war minus the shooting. It is easy to think that the Olympic events were meant to foster skills useful in warfare; the ancient Greeks themselves used this argument to justify the enormous amounts of public money they spent putting on festivals involving athletic contests. It is a tempting idea not least because the ancient Greek for athletic contest, ag n , was also a word for battle but not finally sustainable.

It is true that the case for a military origin for some of the events can easily be made even for the foot races, if you think in terms of the distance a spear can be cast and followed up, and pursuit of a fleeing enemy; and for the long jump if you imagine it as practice for jumping ditches. But in fact skill at Olympic events would rarely translate into the kinds of abilities needed by a typical Greek soldier. Chariot racing, for example, first introduced in 680 BCE , remained an Olympic sport long after the Greeks had stopped using chariots in warfare. The seventh-century Spartan poet Tyrtaeus even doubted whether athletic ability necessarily developed the kind of courage needed in warfare. And in one of his plays Euripides, the fifth-century Athenian dramatist, had a character (we do not know who) say: Are they going to fight the enemy with discuses in their hands? Will they drive the foe from the fatherland by punching holes in their shields?

Euripides sarcasm is justified. For fourteen successive Olympic festivals in the fifth century, starting with the 70th Olympiad in 500 BCE , there was a mule-cart race. This was clearly not meant to simulate anything that might happen in warfare. Moreover, there were no contests for team sports, which would presumably have been useful in a military context. For the Greeks, the games were an end in themselves; they were driven by love of competition, pride and patriotism, just as modern sportspeople are. The connection between war and sport worked only in the sense that both activities developed strength, endurance, discipline and courage, and because the ethos (and hence the vocabulary) of athletic competition mirrored that of warfare, both requiring violence restrained by respect for regulations.

The Altis as an archaeological site. Note especially the temple of Zeus at the top, and the square Hotel Leonidas at the bottom left.

IURII BURIAK/Shutterstock;

In the formulation of Baron Pierre de Coubertin, the man who devoted his life to reviving the ancient Olympics at the end of the nineteenth century: What is important in life is not success, but the struggle; what is essential is not winning, but competing well (speech delivered on 24 July 1908).

Sacred Olympia

Best of all is water, and gold, bright as firelight, gleams

More than all other worldly wealth. But, dear soul of mine,

If you want a true contest to celebrate, just as you need search

The barren skies for no bright star more warming than the sun,

So the supreme games of which to sing are those of Olympia.

(Pindar, Olympian Odes 1.112)

So sang Pindar of Boeotia, the most famous of the praise-poets of the late sixth and early fifth centuries BCE . Winners of events at the major sporting festivals of ancient Greece commissioned poets such as Pindar to translate ephemeral victory into eternal fame. And they have, arguably, been as successful in that aim as they were in athletic competition, for Pindars victory odes are still read today, nearly 2,500 years after his death and about 2,800 years after the running of the first Olympic race.